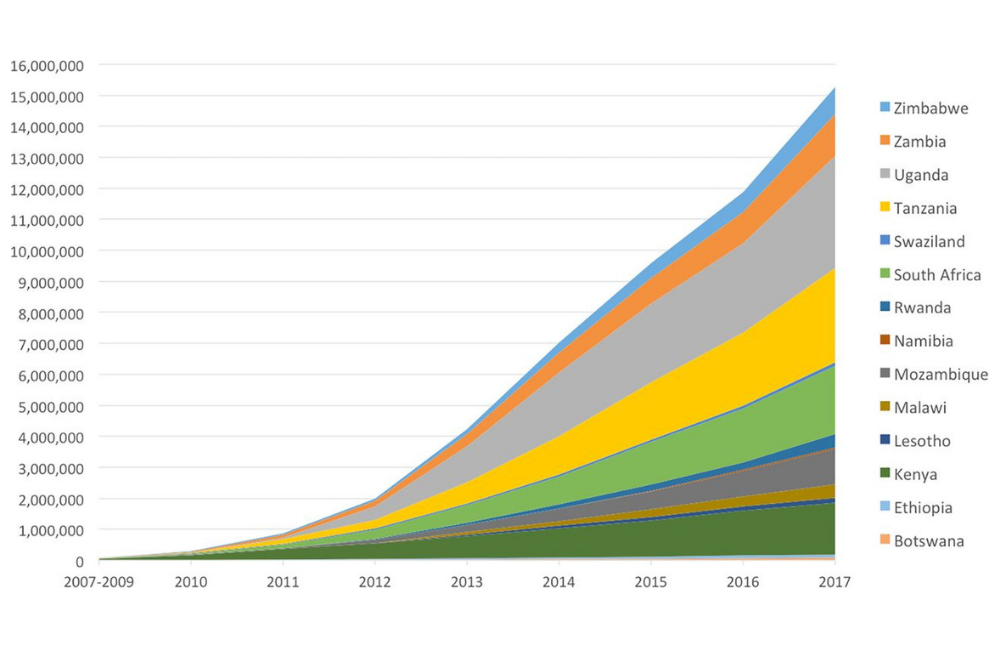

PEPFAR (the US President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief) has supported the voluntary medical male circumcisions (VMMC) of 15,269,720 men and boys in 14 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, in the eleven years to 2017, according to a paper recently published in BMJ Open. The World Health Organization estimates that PEPFAR supported 84% of all VMMCs in the 14 countries.

Research conducted over ten years ago showed that circumcising men reduces their lifetime HIV risk by between 60 and 70%. According to mathematical modelling, the 14.5 million circumcisions performed up to the end of 2016 will result in 500,000 fewer HIV infections by 2030.

From 2010 to 2013, the annual number of circumcisions approximately doubled each year, reaching 2.79 million in 2014. Figures dropped slightly in 2015 and 2016, before reaching 3.38 million in 2017, the highest annual total to date. Over half (54%) of all PEPFAR-supported circumcisions were performed in 2015-2017.

The authors describe this as “a scale-up of historic proportions within global health, comparable with the scale-up of HIV treatment.”

Programme size varied considerably by country, varying from 3.62 million performed in Uganda to 66,410 in Ethiopia. This is partly related to country population size but is also due to their HIV epidemiology; for instance, only two high-prevalence provinces in Ethiopia are covered.

The programme originally prioritised men and teenage boys aged 15-29, as it was reasoned that this was the peak age for sexual debut and activity. An unforseen development is that although 48% of VMMCs in 2017 were performed on males of this age, almost as many – 45% – were performed on boys aged 10-14. This proportion has increased slightly in the last few years.

It is not certain why the average age is younger than envisaged, but reasons suggested by the writers include reluctance in older males to abstain from sex for the six-week healing period, perception of low risk in men with established partners, the cost of losing wages during recovery, and fear of being suspected of infidelity. While circumcision in younger boys will still result in a reduction in their risk of HIV once they start having sex, the prevention benefit of the programme will be delayed.

Testing for HIV before the procedure is encouraged in the PEPFAR VMMC programme but not mandatory. Eight per cent of males who underwent VMMC did not test and this proportion has stayed steady, but was considerably more common in Lesotho (50%), Namibia, Ethiopia and South Africa (20%). Only 1% of those who tested were HIV-positive – much lower than the HIV-positivity among the general male population aged 15-49 in the 14 countries of 5.5%, mostly due to the young age of VMMC attendees.

The proportion of men who attended follow-up appointments within 14 days of their VMMC procedure was generally good and improved from 72% in 2015 to 84% in 2017. Individual country rates ranged from 100% in Rwanda to 59% in South Africa.

There were significant declines in the number of VMMCs performed in Uganda and Rwanda between 2014 and 2016. This was largely due to a cluster of cases of tetanus occurring in VMMC recipients in Uganda. The situation was resolved by 2017 (in Uganda, by making tetanus vaccination mandatory before VMMC). In that year VMMCs in Uganda doubled relative to the previous year and in Rwanda they more than tripled. As Uganda has the largest PEPFAR VMMC programme, these events had an impact on the overall PEPFAR figures.

The writers of the paper say that the VMMC programme has had benefits over and above reducing the lifetime risk of HIV infection to heterosexual men by roughly two-thirds. As well as offering protection from some other STIs, it “has connected them with additional HIV and other health services through testing, STI screening, and referrals for other health conditions.” Men who are circumcised are also less likely to pass on HIV and some other STIs to women.

In addition, as a paper published last week commented, the VMMC programme has involved engaging young men, a traditionally hard-to-recruit population, in the idea of protecting themselves for HIV. Its approach, which has included appeals to traditionally masculine ideas of strength and responsibility, may help in reaching men who need to be targeted by other prevention methods such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Davis SM et al. Progress in voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention supported by the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through 2017: longitudinal and recent cross-sectional programme data. BMJ Open 2018, 8:e021835. Doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021835.