Gay men in England who have recently become HIV positive describe a complex web of factors which may have contributed to their infection, according to a qualitative study recently published in BMJ Open.

“Individuals who experienced multiple stressors, gradually over the life course or more suddenly, were especially vulnerable to HIV and being drawn into sexual risk situations, while the social environment created a context that enabled risk of HIV infection,” the researchers write. Individual and interpersonal factors frequently combined with community or structural factors, such as the widespread use of dating apps, chemsex and HIV treatment, as well as changing perceptions of the seriousness of an HIV infection.

The study paints a picture of the personal and social contexts within which gay men are acquiring HIV in the UK. Each year, more than half of HIV diagnoses in the UK are in gay men.

The study

In early 2015, Annabelle Gourlay of University College London and colleagues recruited 21 gay men who had recently been diagnosed with HIV in London or Brighton and who had, tests showed, very recently acquired HIV (usually just a few weeks before diagnosis). They were interviewed on average six months after the estimated date they were infected. The researchers selected men infected recently on the assumption that they were more likely to recall accurately how they got infected than men who acquired HIV longer ago.

Participants were aged between 22 and 61 (median 38) and were mostly white, well educated and employed. The in-depth interviews covered personal background, moving to London/Brighton and experiences of this transition (if applicable), life in recent years before HIV diagnosis, relationships, and perceptions of the circumstances at the time of HIV infection.

The researchers note two potential limitations of their study. Firstly, the experiences of white gay men in large urban centres may not be generalisable to men in other ethnic groups and geographical areas. Secondly, responses may have been limited by social desirability bias, in other words a tendency to answer questions in a way that will be viewed favourably by others.

Individual and interpersonal factors

Many respondents described difficult experiences during childhood which had long-lasting impacts on mental health, drug use and support. Many described dysfunctional or superficial relationships with their parents, family members who had alcohol or mental health issues, or being bullied at school. One man said:

“My father was…an alcoholic and he used to beat my mother and me…That may have had some impact on how destructive one is, and the fact I never had any unconditional love is something that I have struggled with in adulthood.”

One man who said he had never ‘felt nurtured’ by his parents explained:

“I always need validation from people…and that manifests itself in a sexual context.”

A few men grew up in environments where gay men were highly stigmatised, which could result in repressed sexuality or low self-esteem. While most participants had ‘come out’ as teenagers or young adults, others only disclosed their sexual orientation in their twenties or thirties. In some cases, this was associated with resentment of having missed opportunities and a desire for sexual exploration.

“Growing up in an environment where you are getting to know yourself quite late, you get to…thinking about experiences and seeing other sexual stuff that you might not have needed to think about before because you are a bit behind…You know, am I missing out on stuff?”

Recent stressful events experienced before HIV diagnosis caused psychological distress for many participants. These included severe illnesses or deaths of relatives, relationship break-ups, violent partners, loss of friendships and health problems.

A number of men were exposed to multiple psycho-social risk factors and the combination could be devastating.

“I was probably overwhelmed, you know. I wasn’t in a stable place, I wasn’t in a stable relationship, I wasn’t stable financially and I had just suffered some pretty serious losses in terms of my immediate family. It was kind of all over the place really.”

Some men experienced a ‘mid-life crisis’.

“I mean it probably was the perfect storm you know, they [drugs] got me at a time…mid-forties when I wasn’t that secure, there were a few issues, I was looking for fun…it was an escape and it seemed at the time that it was…enjoyable.”

Emotional trauma could make men re-evaluate the potential costs of unsafe sex.

“I didn’t value my life… Because so much had happened and I’d been through so much in the past three, four, five years with…break ups and losing everything and emotional things and deaths and God knows what else, it almost becomes a bit “all my life has just been so crap anyway what’s the point, do I really care if I get it [HIV] anyway?”

Community and structural factors

Men were attracted to London and Brighton for their open-minded culture, freedom and social opportunities. Almost all had met partners at saunas, clubs, chill outs (parties often involving drugs and group sex) or cruising grounds. The temptations of the gay scene could be hard to resist.

“You go to Vauxhall [gay district in south London] on a Friday night as a gay man and don’t come home until five days later. I think there is so much to tempt young people these days, I include myself in that.”

Dating apps provided convenient access to multiple sexual partners for many participants, regardless of age. They could also introduce men to chill outs and chemsex, and some interviewees felt that they promoted promiscuity and irresponsibility. Several men recalled changes in the cultures of sex and drug use on the gay scene.

“Drugs have changed…there are more choices…GHB, mephedrone…which I was quite scared of in the beginning…but then it’s normalised in the gay scene and you just tend to do what other people do. Same thing goes for injecting. I mean these days it’s not seen as so scary.”

Interviewees, especially middle-aged and older men, described the shifting perception of HIV in the gay community.

“I think in London it's almost got to the point where people are not that concerned about it anymore. It's not looked at as a death sentence. I remember reading an article by a doctor, which I know a lot of gay people seem to have read…that he would rather have HIV than diabetes.”

Thanks to the availability of effective HIV treatment and good medical care, HIV was widely perceived to be a manageable condition. This affected behavioural norms and attitudes to risk.

“Everyone knows somebody positive now and knows that they're fit and healthy and they take a few pills a day…That's a huge factor in why so few people use protection anymore…because it has become a treatable illness…I think it changed everyone's risk calculations, because even if the worst did happen, it was no longer the worst.”

Some of the younger participants made conscious choices to engage in condomless sex, including with HIV-positive partners who had an undetectable viral load. Several had used post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and a few had unsuccessfully tried to get pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) from their sexual health clinic. (PROUD study results were first reported in October 2014 and the interviews were conducted in early 2015.)

Generally, many respondents felt that there was a sense of apathy towards risks and susceptibility to HIV in the gay community. They attributed this to the availability of HIV treatment and newer prevention options, the increasing understanding of undetectable viral load, declining stigma and changing perceptions of HIV.

A complex interplay of factors

While a few interviewees explained their infection in terms of a single factor, most participants thought that a combination of factors contributed to risk behaviours and HIV infection.

“The sex and the drugs and the apps all intertwined simultaneously and I can’t really say which one led to the other.”

The researchers note that there was often an interplay between individual, community and structural factors. For example, one man in his twenties felt that his self-harming sexual behaviours stemmed from childhood and a violent relationship with his mother, but also highlighted the role of the ‘abusive’ environment, including gay saunas.

“I think with the sex, I think it’s…environment, especially in South London. The increase of risk sex, chemsex, is becoming an epidemic, in my opinion. You hear of so many young gay men now who are positive…and through this lifestyle. It’s very hedonistic, really nasty…I think, subsequently, living in South London has made me get HIV.”

Psychological issues and drug use were often mentioned in combination. For example, a man in his forties identified the important factors in his HIV infection as:

“The drugs…but also depression because I didn’t care about taking risks…I gave up.”

Some participants who had experienced stressful events suggested that changing perceptions of HIV had consciously, or subconsciously, influenced their behaviour. Risk-benefit decisions were altered.

“When we were young adults, the fear of God was put into us. If you got it you died…Now it is manageable…you could live a normal life…I think the trauma I have gone through has changed what I perceive as real risk in life… There are far more important things…So it was a combination of all those different aspects, I had come to the conclusion that if I did become HIV-positive it wouldn’t be a big event in my life.”

Conclusions

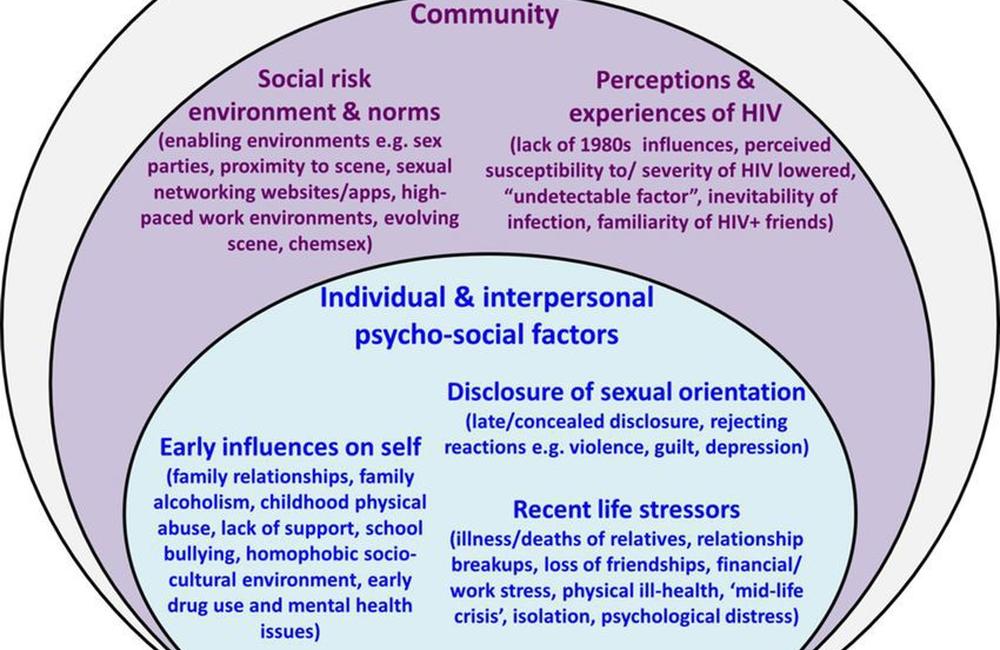

The researchers worked with a socio-ecological framework to guide their analysis. (See graphic here). This suggests that the factors which may contribute to HIV infection can be considered to operate at three levels:

- individual and interpersonal (e.g. difficult family relationships, recent stressful events)

- community (e.g. an environment which normalises risk taking, community perceptions of life with HIV)

- structural (e.g. the availability of HIV treatment, the availability of recreational drugs).

“Recently acquired HIV infection among MSM [men who have sex with men] reflects a complex web of factors operating at different levels,” they conclude.

The relative importance of factors at each level varied for each person. They give three examples, showing how for each person, factors at more than one level interacted with each other and contributed to his HIV infection. (In this graphic A, B and C each represents a different interviewee.)

“The circumstances surrounding HIV acquisition are complex and therefore require multi-level interventions that address individual and interpersonal psycho-social, community and structural-level risk factors,” the researchers say. They say that such multi-level interventions might include:

- improved clinical assessments to identify HIV-negative men who need more support

- tailored psycho-social support for young gay men

- outreach activities to link socially isolated men to peer support

- community education about chemsex

- training to help health professionals have culturally competent discussions with gay men about chemsex and risk behaviour

- counselling interventions provided on dating apps

- programmes to raise awareness of the social and psychological implications of an HIV diagnosis

- access to PrEP.

Gourlay A et al. A qualitative study exploring the social and environmental context of recently acquired HIV infection among men who have sex with men in South-East England. BMJ Open 7:e016494, 2017. (Full text freely available.)