For new mothers with HIV, whether to breastfeed their baby has been a difficult choice. Unlike transmission through sex, viral suppression through antiretroviral therapy (ART) may not completely remove the risk of transmission.

One of the largest studies, from sub-Saharan Africa, found 0.6% of babies born to 1220 mothers who were taking ART became HIV positive themselves within 12 months. But that study did not monitor maternal viral loads. Data from a Tanzanian cohort presented at the 2017 EACS conference found no transmissions from a mother with an undetectable viral load, but not enough is known about viral dynamics in breast milk to be sure whether or not there might be intermittent levels of transmissible HIV.

Complicating the issue is the fact that different advice is given to women in high-income and lower-income countries. In the latter, because of the danger of water contamination and the cost of formula feed, the risk/benefit balance is on the side of breastfeeding and HIV-positive mothers are recommended to breastfeed. In high-income countries, because of the lack of complete certainty on safety, most countries have advice similar to that in the British HIV Association’s pregnancy guidelines, which state that BHIVA “continues to recommend formula feeding by women living with HIV to eliminate the risk of postnatal transmission.”

BHIVA do not, however, completely rule out breastfeeding. The guidelines also add that if mothers wish to breastfeed they should be supported in doing so, as long as they fulfil criteria that include “being prepared to attend for monthly clinic review and blood HIV viral load tests for themselves and their infant” during breastfeeding and for two months after stopping it.

Swiss HIV guidelines were revised in 2019 to offer mothers a discussion of the risks and benefits of breastfeeding, allowing them to make a choice between formula feeding and breastfeeding.

If HIV-positive women are formula feeding they are not expected to take an HIV viral load test more often than they would normally. Their babies receive a PCR test for HIV at one and five months of age and a full antibody screen at two years.

If mothers wish to breastfeed, they attend an antenatal multidisciplinary meeting with a midwife, an obstetrician, and adult and paediatric HIV doctors where the possibility of transmission and how to avoid it is explained, and they receive intensified viral load monitoring. An HIV PCR test on umbilical cord blood is done at delivery; mothers have viral load tests one, three and five months after delivery and every three months thereafter while breastfeeding, plus a test three months after stopping it.

Dropped from the guidelines since 2016 has been perinatal zidovudine (AZT), and any pre-exposure prophylaxis for the baby while the mother stays virally undetectable. Provision for post-exposure prophylaxis for the babies is made in the event of a detectable PCR test in the mother, but it was not needed in the cohort discussed here.

After the guidelines were changed in 2019, a prospective observational study was conducted including every expectant woman in the Swiss Mother and Child HIV Cohort (MoCHIV) which enrols the majority of HIV-positive mothers in the country. At the 18th European AIDS Conference (EACS 2021), Dr Pierre-Alex Crisinel of Lausanne University Hospital reported on this cohort.

In a small country with low prevalence, there were only 41 women in the cohort. Of these, 20 or nearly half decided to breastfeed despite the additional monitoring requirements.

All 41 women had an undetectable HIV viral load before delivery, and their mean CD4 count was 649.

The women’s average age was 34, with no significant difference between women who decided to breastfeed and ones who did not. Of 36 women with known ethnicity, 22 were Black African, ten White European, one White Latina and three Asian. More White European women decided to breastfeed than not to (seven versus three) and among the Black African women 12 breastfed and ten did not. These differences were not statistically significant.

For 56% of women, this was their first baby.

The only significant predictor of choosing to breastfeed was length of HIV diagnosis. On average, the women had been diagnosed for 6.5 years, but those who chose to breastfeed had been diagnosed for 10.5 years, and those who did not, for 4.5 years.

Three-quarters of those who breastfed were still doing so three months after having their baby and 45% six months after.

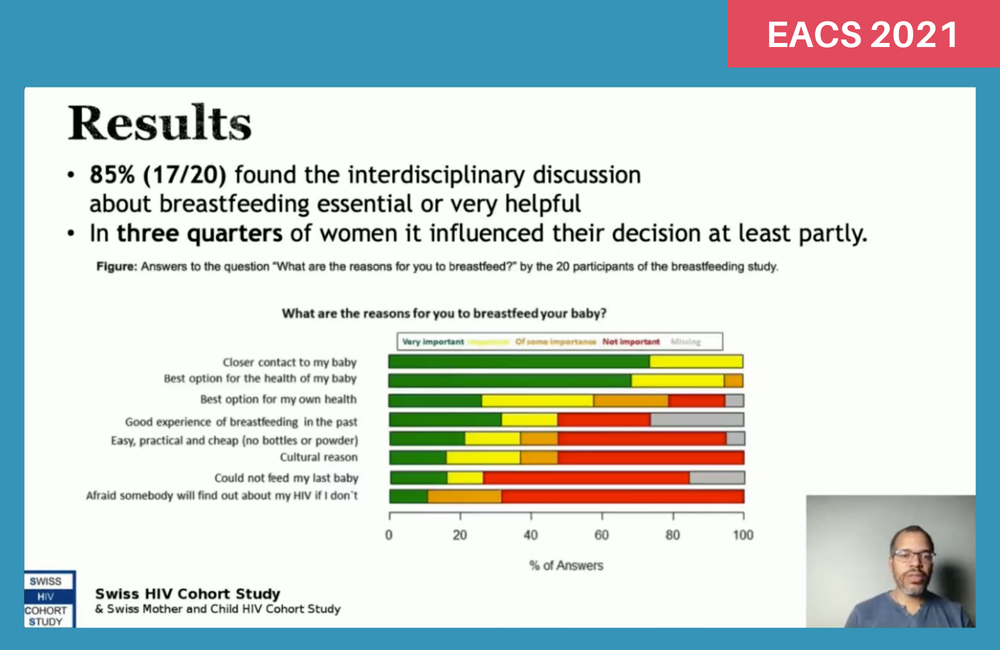

The women who breastfed were asked about the reasons for their choice. Eighty-five per cent said the antenatal multidisciplinary meeting had been helpful and 75% said it had influenced their decision.

The women were asked to select their reasons for choosing breastfeeding from a prompt list and say which factors had been most important.

All women said that closer contact and bonding with their baby was an ‘important’ or ‘very important’ reason for their decision, and all but one woman said that breastfeeding being the best option for their baby’s health was an important factor. Just over half (eleven) said that their own health was an important consideration in making their decision too.

Other reasons were cited less often. Only six of the 20 said that breastfeeding being easier, cheaper and more practical was an important consideration and only six said cultural expectations about breastfeeding had been important. Significantly, only two said that fear of disclosure as HIV positive was an important factor in guiding their decision.

Dr Crisinel said that the feeling of being involved in shared decision-making with their healthcare staff had also been very important to them.

Crisinel P-A et al. Successful implementation of new HIV vertical transmission guidelines in Switzerland. 18th European AIDS Conference, London, poster abstract BPD 2/3, 2021.

Update: Following the conference presentation, this study was published in a peer-reviewed journal:

Crisinel P-A et al. Successful implementation of new Swiss recommendations on breastfeeding of infants born to women living with HIV. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 283: P86-89, April 2023.

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2023.02.013