The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) used 27 September, National Gay Men’s HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, to announce that HIV diagnoses had fallen in white gay and bisexual men and remained stable among African-American gay men between 2010 and 2014, its last complete year of figures.

The CDC went further in its release: for the first time, it attributed this slowing of diagnoses to “the prevention effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (ART)” and said that data from three studies had convinced it that people who take ART as prescribed and maintain an undetectable viral load “have effectively no risk of sexually transmitting the virus to an HIV-negative partner”.

This form of words is important. It marks a break with the CDC’s previous formulation that viral suppression “greatly reduces the chance” of HIV transmission. The change in wording is being attributed both to data such as that from the recent Opposites Attract study, and to the lead given by the Prevention Access Campaign and its “U=U” (Undetectable equals Untransmittable) message.

Bruce Richman, founder of the Prevention Access Campaign, told aidsmap.com: "The CDC’s updated risk assessment is a historic shift in what it means to be a person living with HIV, and provides a powerful argument for universal access to treatment and care for both personal and public health reasons."

How many US gay men are virally suppressed?

But how many gay men in the US are virally suppressed? The CDC release says that 61% of gay and bisexual men diagnosed with HIV have a viral load of below 200 copies/ml, their definition of suppression. This is based on a more detailed report in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR: Singh et al.) for 22 September.

This does indeed report that 61.2% of gay and bisexual men who had at least one viral load test in 2014 were virally suppressed.

However, this disguises a lot of detail. Firstly, the data is two years old. Things may have changed since, probably for the better.

The second issue is that the MMWR figures come from the 37 states and one territory (the District of Columbia) that report viral load suppression rates and whether patients are regularly in care. The 13 states that only report HIV and AIDS diagnoses and deaths include some populous ones with high HIV prevalence such as Florida and Pennsylvania, so we don’t have a complete picture.

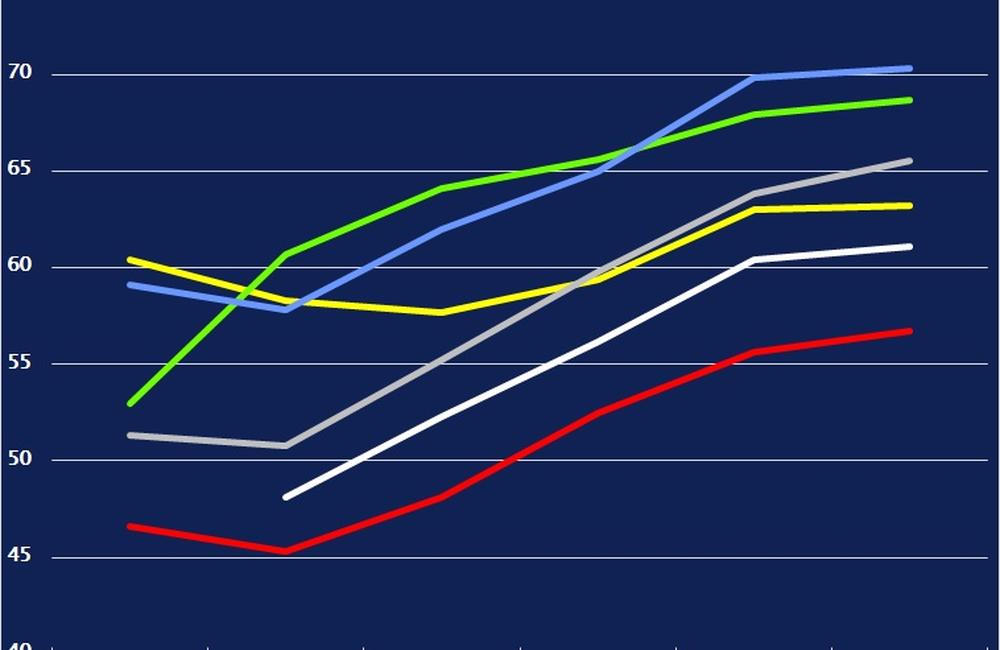

More interesting is the variation between gay men, which varies by ethnicity and age (see graphic). Just over 45% of black gay men aged under 24 were virally suppressed: conversely, about 68% of white gay men aged over 45 were. Viral suppression rates increased among all ethnicities by age – but black gay men over 55 still had a lower suppression rate (57%) than white gay men aged 20-24 (61%).

Then there is the issue of diagnosis. The US has a high diagnosis rate. The CDC estimates that (among all groups and in all 50 states plus DC) only 15% of people living with HIV are undiagnosed, with a slightly higher proportion of gay men (17%). This is even lower among people over 45 (less than 10% undiagnosed). Conversely, however, 44% of people aged 13-24 and 29% of people aged 25-34 are undiagnosed.

This would mean that less than 28% of HIV-positive gay men aged under 25 are actually virally suppressed, and under 39% of 25-34-year olds – but around 60% of men over 55.

In addition, the definition of suppressed viral load is quite lax, requiring only one test result in the previous year. The percentage of diagnosed gay men “retained in care” in 2014 was actually lower than this, at 58%, and 54% in black men. (“Retention in care” is defined as the patient having had at least two CD4 or viral load tests more than three months apart in the previous year.) This might be a better guide to consistent viral suppression than just one test.

Retention in care is the US challenge

This contrasts with figures released by the UK today. The latest Public Health England Surveillance tables show that over 86% of people with HIV in the UK are now diagnosed and in regular care, that 95.5% of these are on ART, and that 97% of these have a viral load below 200 copies/ml, implying that over 80% of all people with HIV in the UK are virally suppressed.

Even so, the suppression rates the US is managing to achieve in gay and bisexual men do seem to be helping to reduce infections. HIV diagnoses fell in white gay men between 2010 and 2014, and have remained largely static among black gay men. Only amongst Hispanic gay men are they still increasing. This racial pattern was similar in other risk groups.

There is an age variation in diagnoses too: 62% of young gay men under 20 diagnosed were black and 53% aged 20-24; conversely, 52% of gay men aged over 55 diagnosed were white. An interpretation of this is that HIV testing rates in black gay men have now, at last, equalled or even exceeded testing rates in white gay men, and this is helping to diagnose recent infections in this population. Testing rates have been high in white men for a long time, so longer-term infections in the minority who have never or rarely tested are the ones now being detected.

The challenge now is to get more people on treatment: the figures suggest that if the US achieved greater retention in care, its HIV infection rate could start to decrease faster.

The CDC National Gay Men’s HIV/AIDS Awareness Day release is here.

The release is based on: Singh S et al. HIV care outcomes among men who have sex with men with diagnosed HIV infection — United States, 2015. MMWR, 22 September, 2017.

The full CDC viral suppression and retention in care data: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using US surveillance data: United States and 6 dependent areas, 2015. HIV surveillance reports, Supplemental report volume 22, no 2. July 2017.