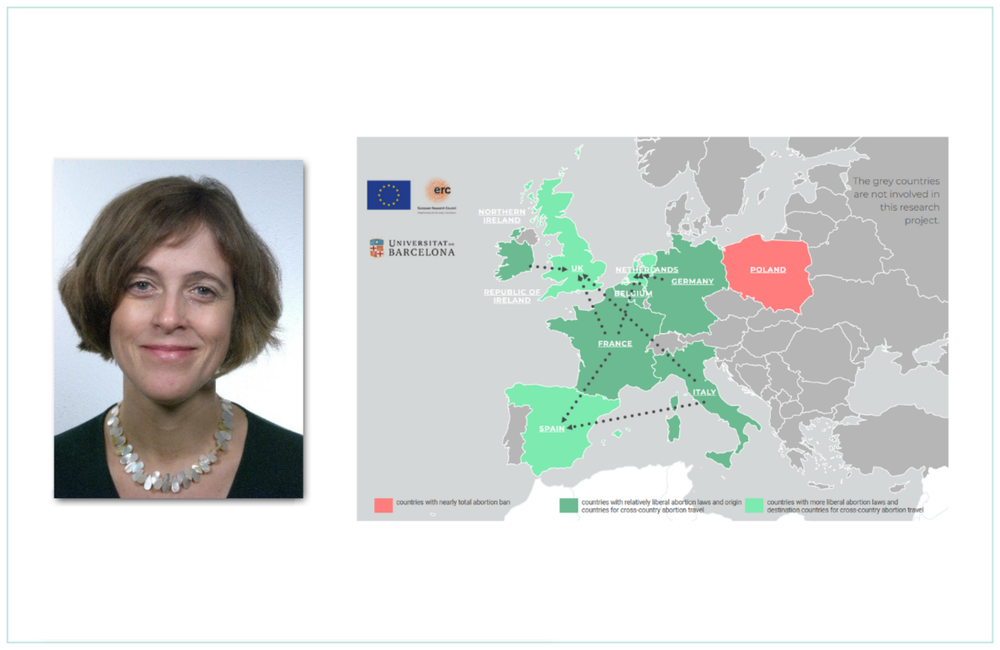

Many women travel across borders in Europe to access abortion care, even when they live in countries with apparently liberal abortion laws. The Europe Abortion Access Project was a six-year research project which set out to understand the experiences of these women. We spoke to the principal investigator, Dr Silvia de Zordo from the University of Barcelona, about the key findings of the research.

What was your starting point for the research?

With my colleagues, Professor Joanna Mishtal from the University of Central Florida, and Dr Caitlin Gerdts from Ibis Reproductive Health, I led a pilot study at three clinics in England between 2014 and 2015. The pilot clearly showed that gestational age limits were the main reason why people from countries where abortion was legal travelled to England for abortion care, and abortion travel was an economic burden for many.

We wanted to better understand this phenomenon. The few available data showed there were thousands of women travelling across borders from countries where abortion was legal. Between 2017-2018, we calculated that over 3800 non-Dutch and non-British residents from countries where abortion is legal sought abortion care in the Netherlands and in England. But there were no studies on this phenomenon specifically, and no mixed-methods study at all.

We designed a study in two phases. One phase looked at cross-border travel for abortion care, and the second aimed to study in more depth the barriers faced by women and pregnant people seeking access to care in three countries in particular: two that were ‘sending’ women abroad, France and Italy, and the third, Spain, which was a ‘receiving’ country. We invited people attending certain clinics in England, the Netherlands and Spain to complete a self-administered survey and/or to take part in an interview with our researcher.

It was interesting because these three countries had similar laws, but abortion provision was organised very differently at national and regional level and barriers to access are different in each country. In Italy, unlike in Spain and France, most abortions are provided by public maternity hospitals. In some regions in the south, where there are very high rates of conscientious refusal of care by clinicians, there are also a few private clinics providing abortion care. If you face high rates of conscientious refusal of care, then this may be a problem in terms of accessing abortion.

At the time of our research, there were low rates of medical abortions in Italy, because mifepristone [one of two medications used to end a pregnancy] was authorised very late and introduced very slowly in abortion services, for a number of reasons. For example, the Ministry for Health recommended hospitalisation throughout the process and, as it can take up to two days, women did not want to do that and it was also a problem for the service providers.

While in Italy there were these barriers and difficulties, in France this was not the case. Over the last 15 years, France has tried to simplify access to abortion and to liberalise the law, so access to medical abortion in the first trimester is relatively easy. It can be provided by midwives and GPs, which is not the case in Italy. However, in some regions of France, particularly in rural areas, it is still not easy to access abortion care and there is some conscientious refusal of care too.

What are the gestational age limits?

Gestational age limits for abortion care vary. In most countries in Europe, the limit for abortion on request is 12 weeks and after that there are more restrictions. But in most countries, the law does not specify whether these 12 weeks are counted from conception, or from the last menstrual period. It comes down to how it is interpreted on the ground, by medical authorities or abortion providers, and that can vary.

In Italy, the limit is calculated from the last menstrual period, while in France and Germany, it is from conception. That means people may have two more weeks or two weeks less to obtain access to care, which can make a big difference.

In the second trimester (12-24 weeks), in France and Italy, accessing abortion care is very complicated. You have to prove that you are suffering from serious physical or mental health problems, and that can be difficult.

In Spain, accessing abortion care up to 22 weeks is relatively easy. There is a first limit at 14 weeks for abortion on request. After that, you have to prove that you are suffering from physical or mental health problems, but only one doctor needs to certify that and usually abortion clinics have their own psychiatrist. This is why Spain is one of the receiving countries for pregnant people who cannot access abortion beyond the first gestational age limit.

What did the study find?

Firstly, this study clearly confirmed what we found in the pilot study, which was that most people travel across borders from countries where abortion is legal due to the gestational age limits that are established at the end of the first trimester by most legislations.

And why do they exceed gestational age limits? In most cases, they experience irregular menstruation or they don’t have clear pregnancy signs, so they are unaware of their pregnancy in the initial weeks. Sometimes this is combined with stressful life circumstances, like a separation, divorce, or serious sickness of a relative. Sometimes, their GP did not help them understand their pregnancy signs and actually contributed to their confusion. Some were in the process of changing their contraception and their GP was not always able to understand that the signs were not due to this change.

This was one of the key issues. You can simplify and improve access to abortion in the first trimester, but you will not meet the needs of everyone seeking abortion care, because for a number of reasons they may confirm their pregnancy around 12 weeks or just beyond. Why should you then become a criminal for seeking abortion care? It’s kind of bizarre, as an idea.

Almost one third of our survey respondents confirmed their pregnancy at less than 14 weeks, meaning that they were still below the legal time limit, at least in France and Germany. They still had legal time to have an abortion, but they couldn’t – and why? This is the other issue; they faced a number of barriers to access.

What barriers to access do women face?

The first issue of access is around accessing information. Not many countries have great publicly funded websites, which tell you clearly about the law, the available techniques, gestational age limits, all the services near you – these are the exception. Information was a serious concern in countries like Germany and Italy and this can delay access to care.

A further barrier was mandatory waiting times, or mandatory counselling. Mandatory counselling is an issue in Germany. You lose more time, because you have to find a service, find a counsellor, make an appointment – and if you are very close to the gestational age limit, a matter of days can make a big difference.

In Italy, the issue of conscientious refusal of care blurs with the issue of accessing information. In some cases it was clear that doctors were objectors and in some cases it was not, but women were not provided with the clear and timely information they needed. They were not always referred on, and this was why some people exceeded the time limit.

Some people were so nervous about the gestational limit that if their first contact with health services was difficult, they would go abroad even if they still had a few days to go.

It’s important to recognise that these barriers to accessing information and services were a reason for people exceeding the gestational age limits.

What are the implications of travelling for abortion care?

Travelling across borders implies a number of costs. First and foremost, there are economic costs. On average, the cost of the abortion procedure was around 962 euros. This is because it is a second trimester abortion – a surgical procedure called dilatation and evacuation (D&E). These costs are not covered or reimbursed, so people have to find this money themselves. In addition, there are travel and accommodation costs for themselves and anyone accompanying them.

Almost 20% of our survey respondents said they needed between one and four weeks to raise money for the abortion procedure and travel, and 7% said they needed more than four weeks.

We’re talking about people who are already close to or have just exceeded the 12 weeks. When you add 2, 3, 4 weeks, it becomes something else. For them it is very stressful, because it becomes evident that they are pregnant and they feel very pregnant. It’s difficult to negotiate in their daily life, and it’s difficult to keep it a secret if that’s what they want to do.

We talked to young women who wanted to keep the pregnancy secret from their family, but in the end they had to ask them for financial help – that’s an issue of confidentiality.

Furthermore, up to 18 weeks, if an abortion is performed following established international medical protocols, it is very safe. From 18 weeks, complication rates increase. This means people are exposed to risks that they may not have been exposed to if they had been able to access care at the point when they decided to have the abortion, where they live.

Eighteen per cent of our survey respondents reported moderate to severe financial insecurity. Having to travel abroad is an experience that deepens existing social and gender inequalities and, because it is so difficult, some looked for alternatives.

Around 6% of the survey respondents recruited in the Netherlands told us they tried to end their pregnancy on their own, before travelling. We thought that, because information about medical abortion is available online, people might have tried to buy misoprostol, which is one of the safe abortion pills used to terminate pregnancies both in restrictive and legal contexts.

What was very shocking to us was that this was not what these respondents described. Most tried to end their pregnancy by hitting their abdomen, which was harmful, and some took other drugs that had nothing to do with abortion pills – and of course this was not effective. It is possible that in countries where abortion is legal, but self-managed medication abortion is not, women and pregnant people do not have easy access to information on this safe abortion method. We completed data collection before the pandemic, during which a few countries started to provide self-managed medication abortion via tele-health. Hopefully now there is more information about this method.

A final point is that in order to be able to travel abroad, you have to make arrangements for your work and family and this also has a cost. Thirty-eight per cent of our survey respondents already had children, so they had to arrange for childcare too.

Of course, we only met women who had made the journey abroad for care. There will be others who could not raise the funds to travel and either carried an unwanted pregnancy to term, or sought abortion methods that may be unsafe.

What needs to change?

We asked our interviewees what they thought and they clearly stated that gestational age limits should be extended to the end of the second trimester.

They also told us that the law should be more personalised and open, in the sense that it should allow the assessment of individual cases and should not establish strict and specific circumstances under which abortion is allowed or not. Having specific gestational age limits often obliges people to make quick decisions and sometimes these decisions may not be easy and may require time.

We hope that they will be listened to. But with the current backlash against abortion rights, particularly in eastern Europe and the US, there is a nervousness among pro-choice groups in the European Union. It makes the issue of gestational age limits a difficult one to tackle.

For more information

All the publications from this extensive research project are available on the project website: https://europeabortionaccessproject.org/

The project was funded by the European Research Council – ERC BAR2LEGAB 680004.

This feature first appeared in the May 2023 edition of the Sexual Health and HIV Policy Eurobulletin.