There are important gaps in the HIV treatment cascade for migrant populations in Australia, especially at the stage of diagnosis, according to a study recently published in PLOS Medicine. People born in other countries did not do as well as the general population in terms of HIV testing, staying in care, receiving treatment, and reducing their viral load to undetectable levels, with variation between different groups of migrants.

The United Nations (UNAIDS) 90-90-90 target of getting 90% of people with HIV diagnosed, 90% of those diagnosed on treatment and 90% of those on treatment virally suppressed by 2020 has been well publicised. Some countries have already reached 90-90-90, but in most cases what the figures do not show is whether there is any variability within the total. In other words, do some sections of the population do better than others?

Migrants make up a considerable proportion of people with HIV globally, but we don’t know exactly how they fit in the treatment cascade. A group of researchers based in Australia wanted to find out if migrants with HIV do reach the 90-90-90 target and then if particular groups of migrants do better than others. They focused their attention on Australia, which has a very significant migrant population – currently 29% of its population are born abroad. Most HIV-positive migrants in this study were from south-east Asia (28%), northern Europe (12%), and eastern Asia (11%) with some from sub-Saharan Africa.

In Australia, citizens and permanent residents have subsidised general healthcare access, including HIV care services, via the national health insurance scheme Medicare. Temporary residents from New Zealand and ten European countries are eligible for subsidised access through Medicare through reciprocal arrangements between Australia and their home countries. People who are from other countries are not eligible for Medicare, although some may manage to access care through compassionate access programmes or private insurance. We might therefore expect them not to do so well in the cascade.

The researchers grouped people into migrants and non-migrants based on their stated countries of birth. Migrants who were recorded as temporary residents were also grouped according to whether or not their country of birth has a reciprocal healthcare agreement with Australia. The authors used data including whether or not a person was on treatment and their viral load to develop the HIV cascades for migrants. The migrants cascade was then compared to the cascade of non-migrants covering the period 2013 to 2017 in the states of New South Wales and Victoria.

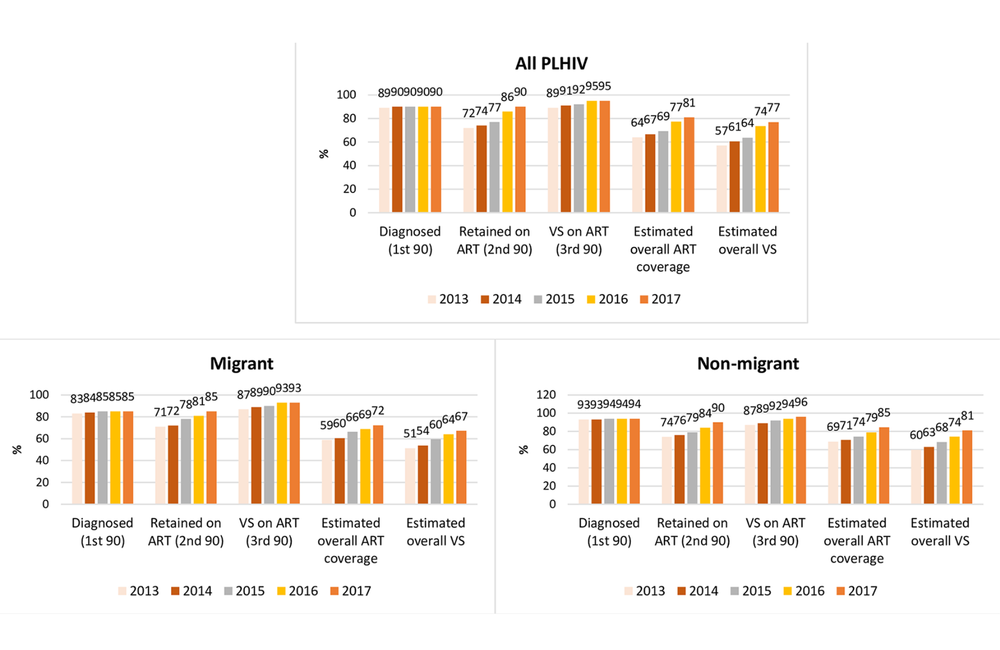

They discovered that migrants’ cascades were less good than non-migrants’ cascades. Although the overall cascade in these states was high (90-90-95), this disguised an inequality between migrants and non-migrants. The migrants’ cascade was 85-85-93. That’s to say, 85% of migrants with HIV were actually diagnosed, of those 85% were on treatment, and of those 93% had undetectable viral load. This compares to the non-migrants’ cascade of 94-90-96 in which 94% of those with HIV were actually diagnosed. Interestingly, in both cases it appears that if a person is both diagnosed and on treatment, they have a high likelihood of achieving undetectable viral load. To get migrants up to the same level though, they need to be diagnosed.

"Although the overall cascade was 90-90-95, this disguised an inequality between migrants and non-migrants."

The researchers found some variation across different population groups within these two broad cascades. For example, migrants born in south-east Asia had poorer cascades (72-87-93) compared with those who were born in sub-Saharan Africa (89-93-91). Similarly, migrants from countries not eligible for the reciprocal care agreement had poorer cascades (83-85-92) than those who are eligible (96-86-95). Within these figures was an even sharper difference for men who reported having sex with men: migrants reporting sex between men had a cascade of 84-87-93 compared with non-migrants 96-92-96.

In their conclusion the authors point out that although the overall cascade improved through the period 2013 to 2017, improvements in the cascade for migrants lagged behind. They also note that migration is a global issue, and that global migration is increasing. They say that it is important to monitor HIV diagnosis and the care cascades in all subpopulations to ensure that no one is being left behind, and that such monitoring is needed if the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target is to be reached.

Interestingly this study also showed that women had lower cascades irrespective of whether they were migrants (87-79-90) or non-migrants (92-70-88). However, the authors do not explore this further.

Marukutira T et al. Gaps in the HIV diagnosis and care cascade for migrants in Australia, 2013–2017: A cross-sectional study. PLOS Medicine, 17: e1003044, March 2020 (open access).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003044