Whether HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is effective depends on whether people take it appropriately, at the times when they are at risk of HIV. But we know surprisingly little about how people receiving PrEP through health services take PrEP, in terms of whether they take it correctly, how long they take it for, and whether this matches periods when they are at risk.

A study of people using PrEP conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found a wide variation in the average length of time people stayed on PrEP after starting it. Dr Ya-Lin Huang of the CDC defined this measure as PrEP persistence rather than adherence, which she defined as the degree to which someone sticks to the correct dose and frequency. The study was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2019) in Seattle.

The study looked at PrEP takers within two large cohorts – the IBM MarketScanR commercial database, which selects recipients of employer-provided medical insurance who work for 100 randomly selected companies, and the IBM Medicaid database, which selects recipients of Medicaid from 8-10 randomly selected (and unidentified) US states each year.

The researchers found 7250 commercially insured PrEP users and 349 Medicaid-covered PrEP users, aged 18-64 who started PrEP between the beginning of 2012 and the end of 2016. Persistence was defined as the timespan between starting PrEP and the person failing to return for a repeat prescription for more than 30 days after the date when their last prescription ran out (assuming they had daily adherence). For the purposes of this study, people were not re-included if they re-started PrEP after a gap of more than 30 days.

Only 2% of PrEP users in the employees’ database were women, though because it was a large database that still left 131 women. There was a higher proportion of women in the Medicaid database (22%) meaning there were 208 women in the two cohorts. Most people in both cohorts were aged between 25 and 44 (61% of the employee cohort, with 11% aged between 18 and 24). The employee cohort did not record race but in the Medicaid cohort 43% of PrEP users were white, 23% black and 34% other.

On average people in the employee cohort stayed on PrEP for 14.5 months after starting it; persistence in the Medicaid cohort was half of this at 7.6 months, and only 34% taking it for more than a year.

Men took PrEP for longer than women, on average for 14.5 months versus 6.9 months in the employee cohort, and 8.4 months versus 5.8 months in the Medicaid PrEP users. In multivariate analysis women in the employee cohort were 74% more likely to stop taking PrEP earlier than average, and in the Medicaid cohort 89% more likely.

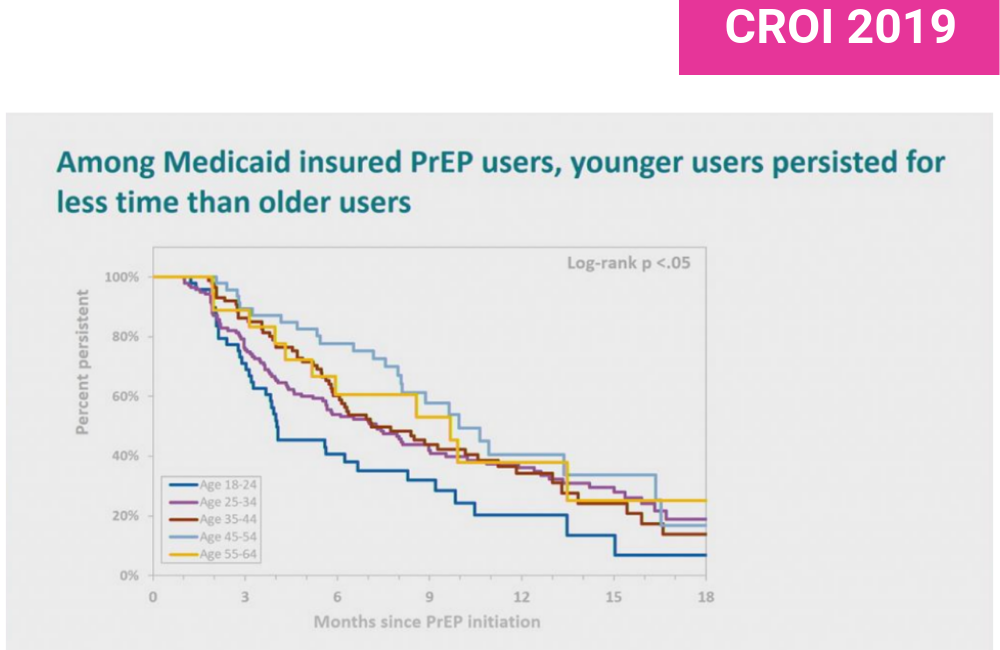

Age was significantly associated with PrEP persistence. People in the employee cohort aged between 45 and 54 took PrEP for 20.5 months on average whereas the 18-24 year olds only took it for 8.6 months. In multivariate analysis that meant 18-24 year olds were 2.45 times more likely to stop PrEP earlier than average than 55-64 year olds. In the Medicaid cohort persistence by age was again roughly half what it was in the employee cohort, with 45-54 year olds taking it for ten months on average and 18-24 year olds for four months.

In the Medicaid cohort, which asked about race, white people took PrEP for 8.5 months on average and 38% lasted for more than a year; people of ‘other’ ethnicity took PrEP for 8.1 months, but black people only four months and only 23% took it for more than a year. In multivariate analysis, however, when other factors were accounted for (such as the fact that black PrEP takers were younger) black people were only 39% more likely to stop PrEP earlier than average and this was of marginal statistical significance.

The employee cohort did divide people by geographic region, but found no regional variation in PrEP persistence. They did however find that the 3% of PrEP users who were classed as living in rural areas were more likely to stop PrEP.

As audience members commented, this study was purely an exercise in sifting through databases and was not able to establish why people might stop PrEP. It also did not count people who came back for more PrEP after 30 days, though Dr Huang said that the results were very similar in sensitivity analyses where gaps of 60 and 90 days were used as the definition of lapsed persistence.

Huang Y-L A et al. Persistence with HIV preexposure prophylaxis in the United States, 2012-2016. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, abstract 106, 2019.

View the abstract on the conference website.

Watch the webcast of this presentation on the conference website.

Update: Following the conference presentation, a further analysis (with more data) from this study was published in a peer-reviewed journal:

Huang Y-L A et al. Persistence with HIV preexposure prophylaxis in the United States, 2012-2017. Clinical Infectious Diseases, online ahead of print, ciaa037, 2020.