The ongoing global monkeypox outbreak differs in several ways from historical transmission patterns and typical symptoms previously seen in countries in Africa where the virus is endemic, according to the largest case series to date, published yesterday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Almost all cases in this outbreak are among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, and most transmission has been associated with sexual activity. However, experts fear that if not promptly managed with testing, vaccination and treatment, the virus could spread beyond this group and may become endemic in more countries.

“We have shown that the current international case definitions need to be expanded to add symptoms that are not currently included, such as sores in the mouth, on the anal mucosa and single ulcers,” said lead study author Professor Chloe Orkin of Queen Mary University of London. “Expanding the case definition will help doctors more easily recognise the infection and so prevent people from passing it on.”

As aidsmap previously reported, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) reported the first monkeypox case in the current outbreak on 7 May. As of 18 July, UKHSA has identified 2137 confirmed cases in the UK. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control has reported 10,604 cases throughout the European region as of 19 July, while the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has compiled a total of 15,848 cases worldwide, including 15,605 in countries that have not historically reported monkeypox.

Orkin and a long list of colleagues formed an international collaborative group of clinicians (the SHARE-net Clinical Group) who contributed data on monkeypox cases in 10 European countries, the US, Canada, Mexico, Australia, Argentina and Israel.

Altogether they compiled information for 528 cases diagnosed with a positive monkeypox virus PCR test between 27 April and 24 June. Most were diagnosed at HIV clinics, sexual health clinics or emergency departments.

All but one of the people with monkeypox were men, and the remaining individual identified as trans or nonbinary. There were no women in this case series, though several dozen women with monkeypox have been reported by individual countries. Almost all said they were gay (96%), 2% were bisexual and 2% identified as heterosexual.

The median age was 39 years. Fifty-six people were older than 50, and 9% had previously received a smallpox vaccine, showing that prior vaccination is not fully protective. The authors did not state whether any were under 18, but countries have reported a handful cases among children. Three quarters were White, 12% were Latino, 5% were Black and 4% were mixed race.

Looking at HIV status, 41% were HIV positive. Of these, almost all (96%) were on antiretroviral therapy, a majority of them (61%) on an integrase inhibitor. Most had well-controlled HIV, with 95% having an undetectable viral load (less than 50); the median CD4 count was high, at 680. Among the 59% people who were HIV negative or had an unknown status, more than half were on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Hepatitis B (1%) and active hepatitis C (2%) co-infection were uncommon.

"Whilst people with HIV account for more than 40% of cases so far, it is reassuring that HIV status was not linked with monkeypox severity,” said Laura Waters, chair of the British HIV Association.

Monkeypox transmission

According to the study authors, “Transmission was suspected to have occurred through sexual activity” in 95% of people with monkeypox in this case series.

The monkeypox virus is transmitted through close physical contact, which can include skin-to-skin contact, exchange of body fluids and transmission via respiratory droplets at close range, though it does not spread through the air over longer distances. The virus can also potentially spread via clothes, bed linens or surfaces that have been in contact with fluid from lesions, although this appears to be much less common. It is not yet known whether the virus is transmitted via semen or vaginal fluid. Before the current outbreak, monkeypox was not thought to be easily transmitted from person to person, but sexual networks of men who have sex with men have provided a favourable setting for rapid transmission.

Indeed, this group had numerous sexual risk factors. Among those who had undergone sexually transmission infection (STI) screening, 29% tested positive, with syphilis (9%), gonorrhoea (8%) and chlamydia (5%) being most common. Among those with a known sexual history, the median number of sex partners was five in the previous three months. One in five reported ‘chemsex’ (use of recreational drugs during sex) and 32% reported attending sex venues during the previous months. Just over a quarter reported foreign travel during the monthly before diagnosis, mostly to European countries.

“Sexual close contact” was by far the most common suspected route of transmission (95%). About a quarter (26%) had contact with a person known to have monkeypox. Non-sexual close contact and household contact were each suspected in 1% of cases, while 3% had an unknown transmission route.

“It is important to stress that monkeypox is not a sexually transmitted infection in the traditional sense; it can be acquired through any kind of close physical contact,” said lead study author Dr John Thornhill, of Barts NHS Health Trust and Queen Mary University of London. “However, our work suggests that most transmissions so far have been related to sexual activity -- mainly, but not exclusively, amongst men who have sex with men. This research study increases our understanding of the ways it is spread and the groups in which it is spreading which will aid rapid identification of new cases and allow us to offer prevention strategies, such as vaccines, to those individuals at higher risk.”

Symptoms and treatment

Only 23 people diagnosed with monkeypox had a clear enough exposure history to determine incubation time, which ranged from three to 20 days. Most (97%) had positive skin or anogenital lesion swabs and 26% had positive nose or throat swabs. In addition, some had positive PCR tests of blood (7%), urine (3%) and semen (5%) samples.

However, “this may be incidental as we do not know that [the virus] is present at high enough levels to facilitate sexual transmission,” Thornhill said. “More work is needed to understand this better.”

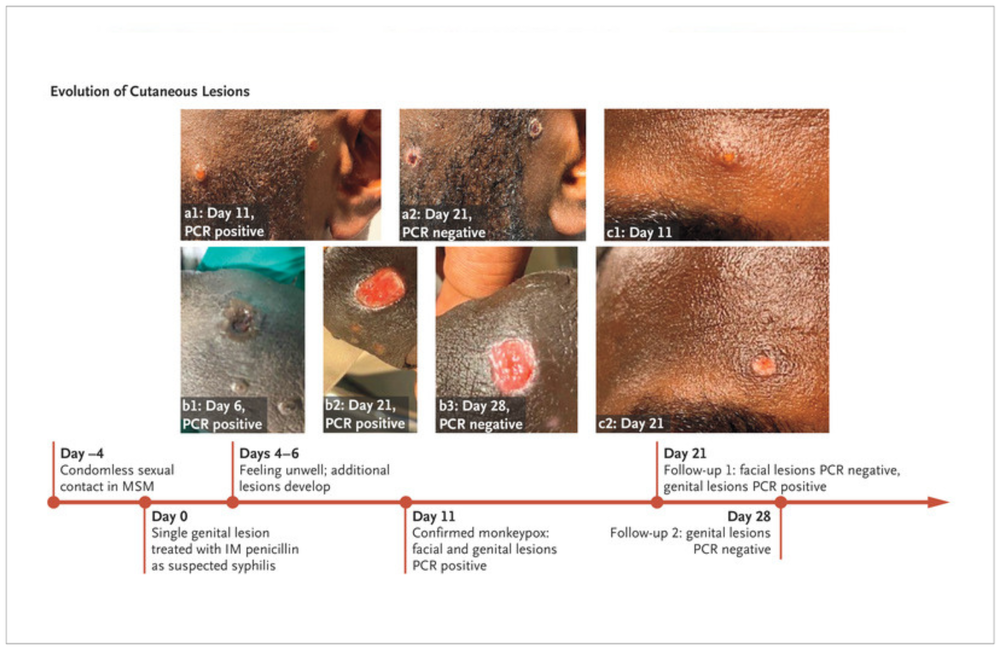

Almost everyone with monkeypox (95%) developed a rash or lesions, including 73% with anal or genital lesions, 55% with lesions on the trunk or limbs, 41% with mucosal lesions (mostly anal, throat or both), 25% with facial lesions and 10% with lesions on their palms or soles. However, 28 people (5%) did not develop lesions. Seventy-five people (14%) reported proctitis, or rectal inflammation. Other common symptoms included fever (62%), swollen lymph nodes (56%), fatigue (41%), muscle aches (31%), headache (27%) and sore throat (21%).

Some people included in the case series presented with symptoms not recognised in current medical definitions of monkeypox, including single genital lesions and sores on or inside the mouth or anus. In some cases, these symptoms resemble those of common STIs, which could lead to misdiagnosis, and some people had concurrent monkeypox and STIs. The study authors stressed the importance of educating health care providers about how to identify and manage these new clinical symptoms.

Seventy people (13%) were hospitalised, mostly for management of severe rectal pain (21 people), soft tissue infections (18 people) or a sore throat that resulted in difficulty swallowing (5 people); 13 were in hospital for quarantine. Two people each had eye lesions, acute kidney injury and myocarditis (heart muscle inflammation). Several men who have shared their stories in the press or on social media have described severe anal or throat pain.

Only a small number of people (5%) were given antiviral treatment, which has been in short supply and difficult to obtain. Two each received tecovirimat (Tpoxx) and cidofovir (Vistide) and one received vaccinia immune globulin (antibody therapy).

No deaths were reported in this case series. To date, there have been five monkeypox deaths this year, all of them in African countries.

“The findings of this study, including the identification of those most at risk of infection, will help to aid the global response to the virus,” according to a press release about the report. “Public health interventions aimed at this high-risk group could help to detect and slow the spread of the virus. Recognising the disease, contact tracing and advising people to isolate will be key components of the public health response.”

The study authors emphasised that public health measures should be developed and implemented in collaboration with at-risk groups to ensure that they are appropriate, non-stigmatising and avoid messaging that could drive the outbreak underground.

“This international case series contributes to the growing evidence of how monkeypox is being transmitted, and in which population groups,” said Dr Will Nutland, co-founder of PrEPster. “The research must serve as a further call to properly resource our responses to monkeypox, including upscaling testing, treatment, and vaccination programmes, to the key populations most impacted by the virus".

Thornhill JP et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries – April-June 2022. New England Journal of Medicine 2022.