Simple measures to improve the ordering and turnaround of viral load tests in Uganda significantly improved viral suppression after one year, a cluster-randomised trial reported this week at the 11th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2021) found.

Although viral load testing is a well-established procedure in Uganda’s national HIV treatment programme, its uptake could be improved. Doctors do not always order viral load tests in situations where national guidelines recommend a test, and turnaround times from ordering the test to delivery of the result to the patient can be up to two months. Delays of this length are especially problematic in pregnant or breastfeeding women or people with detectable viral load who may need to be switched to another regimen to avoid drug resistance.

To test whether improvements in viral load testing procedures translated into better outcomes for patients, Dr Vivek Jain of University of California San Francisco and colleagues designed the RAPID-VL study. The trial tested a package of interventions in a cluster-randomised design, in which 20 clinics were randomised to adopt the intervention package or continue with standard-of-care viral load testing procedures.

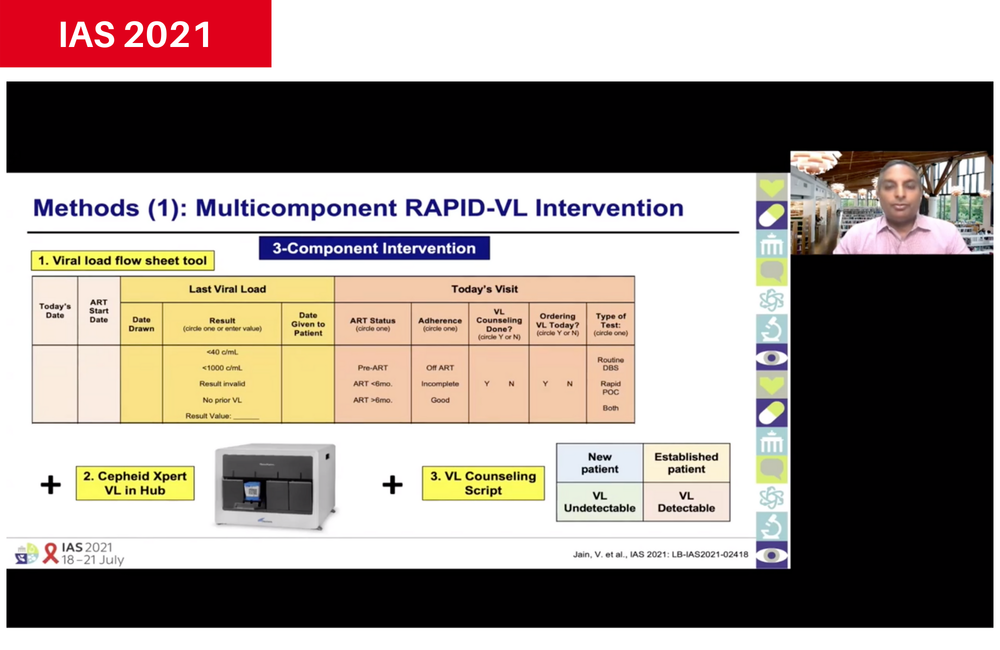

The intervention package consisted of

- A flow sheet in patients' files that required doctors to specify the antiretroviral therapy status and last viral load result of the patient, and to indicate whether a test was ordered, and if it was routine or urgent.

- Availability of Cepheid Xpert near point-of-care device at a local testing hub, in addition to testing of dried blood spots. The Xpert machine has a high throughput and rapid turnaround, so results can be returned to the clinic within days.

- A set of viral load counselling scripts to use with patients in various situations, including detectable or undetectable results. The script used the viral load test result to reinforce adherence messages.

- Regular feedback to clinics on their performance.

The study recruited participants from four groups at higher risk of poor outcomes without timely viral load testing (pregnant and breastfeeding women, children and adolescents, people with detectable viral load and people overdue for viral load tests) as well as adults not at high risk.

The primary study outcomes were time for test results to be delivered to the patient and viral load test ordering that was compliant with guidelines. Outcomes were compared between the year prior to the study and the intervention period (2018-2020) in 1200 people, 60 per clinic. Viral suppression after one year was the secondary study outcome.

The adult study population was 66% female, with an average age of 37 years and had been on antiretroviral therapy for a median of 2.8 years. Children and adolescents were 50% female, with an average age of nine years and on antiretroviral therapy for a median of three years.

In the pre-intervention period, the average viral load turnaround time was 73 days, but ranged from 33 to 89 days between clinics. In the post-intervention period, average viral load turnaround time fell by 67 days in the intervention clinics but remained unchanged in the control group (P<0.0001). The median turnaround time was 1 day in the intervention clinics compared to 56 days in the control group clinics.

Guideline-compliant viral load ordering also improved significantly in the intervention clinics. Whereas test ordering was compliant with guidelines in 70% of intervention clinics and 72% of control group clinics during the pre-intervention period, it increased by 10% in intervention clinics but remained stable in control clinics during the intervention period (p<0.01). Sub-group analysis showed that test ordering improved significantly in all higher-risk sub-groups and in non-high-risk adults.

Viral suppression also improved in the intervention clinics. After one year, viral suppression had improved by 7%, to 83% among those who underwent viral load testing as part of the study, whereas 76% of those in the control group clinics had suppressed viral load after one year. Sub-group analysis showed viral suppression improved in all sub-groups apart from pregnant and breastfeeding women in intervention clinics.

Asked which components of the intervention package may have the greatest effect, Dr Jain said that the study “cannot disaggregate the components because the intervention was designed to address multiple barriers simultaneously. The viral load availability at a local hub is an enabling technology but the prompt sheet helped encourage the use of the technology.”

He said that other countries should consider adopting the hub-and-spoke model employed in the RAPID-VL study, together with the flowsheet and counselling scripts. Feedback from patients and doctors had been very positive, he said. Moreover, the intervention was sustainable in government-run HIV clinics.

Jain V et al. RAPID-VL intervention improves viral load ordering, results turnaround time and viral suppression: a cluster randomized trial in HIV clinics in Uganda. 11th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science, abstract OALD01LB03, 2021.