Differences in countries’ economic prosperity and HIV prevalence do not explain the speed with which they update their national treatment policies and guidelines, but factors related to a country’s political structure are relevant, Matthew Kavanagh of Georgetown University and Health GAP told the 22nd International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2018) in Amsterdam today.

Specifically, countries with more centralised power structures and countries with greater ethnic or linguistic diversity are slower to adopt new guidelines. He suggested that the World Health Organization (WHO) and other agencies should make additional efforts to support countries with these characteristics when guidelines change.

Over the years, there have been a series of important changes in the expert opinion and scientific evidence on when people should begin antiretroviral therapy (ART) – at CD4 cell counts of 200, 350, 500, or regardless of CD4 count. Well-resourced agencies such as WHO, UNAIDS and the President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) define global norms and make their dissemination a priority.

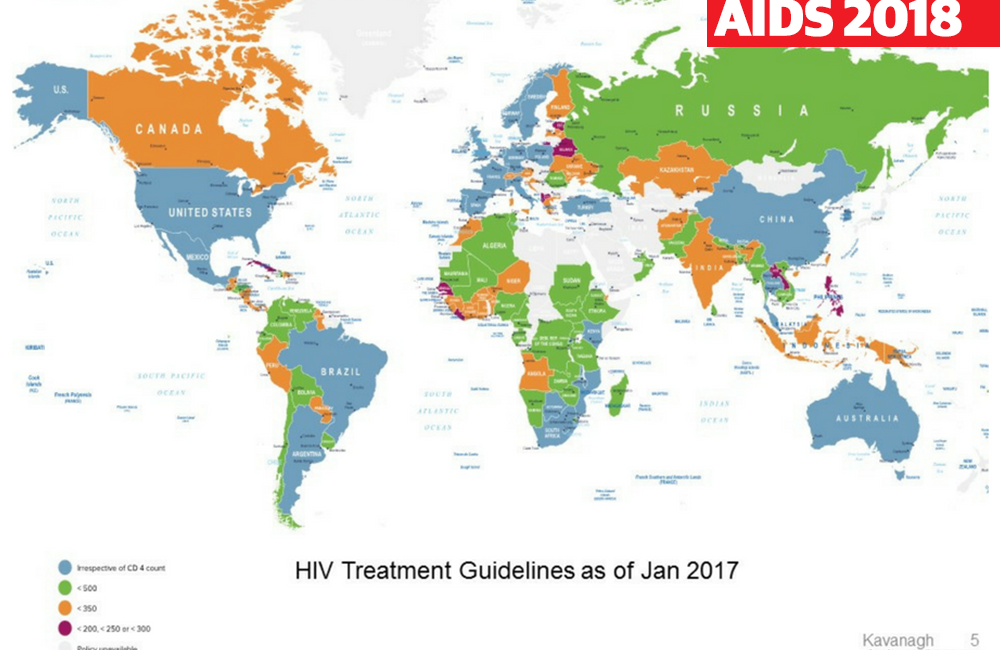

Nonetheless, there is a great deal of diversity in national policies, with many countries lagging behind WHO’s guidelines. Since September 2015, WHO has recommended treatment for all people with HIV, regardless of CD4 count. In January 2017, this approach was being recommended in a number of countries including the United States, some of the larger Latin American countries, most of western Europe, six countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Thailand and China.

Many other countries recommended initiation below 500 cells/mm3. Moreover, some countries continued to recommend waiting until 350 cells/mm3 – including Canada, Ukraine, many west African countries, India and Indonesia. Of even greater concern, delaying treatment until 200 cells/mm3 was still the policy of the Philippines, Senegal, Liberia, Belarus, Macedonia, Cuba and others in January 2017.

For this analysis, Kavanagh and colleagues identified 290 published national ART guidelines for adults and adolescents, from 122 countries (representing 98% of the global HIV burden). They calculated the time difference in months between when WHO recommended a CD4 initiation and when this was adopted as national policy. Associations with a series of social and political factors were calculated.

In addition, he interviewed 25 key informants from 12 countries, in order to shed light on barriers and facilitators of policy change.

While it might be assumed that countries with a greater burden of HIV would feel greater urgency to make changes, HIV prevalence only had a minor impact on speed of adoption.

Similarly, economics and national wealth could be expected to be a factor. However, countries’ gross domestic product (GDP) made no difference to the speed of adoption. Interviewees reported that only a few guidelines took cost into account. Those that did were most often in low-income countries, where there was often political pressure to keep costs down. Formal cost-benefit analyses were not usually demanded.

How democratic a country is made no difference either, but another way of considering the structure of government was important. Kavanagh used a measure known as veto points – countries with low veto points have more centralised power structures. Countries with high veto points have a larger number of bodies or political actors which can influence decision making. Such countries might be expected to have slower decision making (as there are more people who can veto a decision), but there was a strong association between high veto points and faster policy adoption.

Kavanagh said that this was counter-intuitive, but it seems that in countries with complex bureaucratic and political structures, there are more opportunities for professional and community groups to have an influence. Engaged and motivated politicians and lobby groups can be heard, as an informant in the United States explained:

“We count on a few politicos who will pick up the phone to make sure the HHS process is moving.”

Ethnic and linguistic diversity within a country had a strong association with slower decision making. For example, more homogenous countries like South Korea made decisions quickly, while more diverse countries such as Uganda and Indonesia were slower. Kavanagh said that the policy environment in countries with more internal divisions may be more challenging. To influence change in such contexts, it may be helpful to have a variety of ‘messengers’ who can reach different ethnic, linguistic and social groups.

He said that WHO and UNAIDS should take a new approach, tailoring their support to the characteristics of the country. For example, in a country with a more centralised power structure, it is probably necessary to reach decision makers higher up the chain of power.

“The institutional political economy of countries is a stronger and more robust predictor of health policy diffusion than either disease burden or national wealth,” he concluded.

Kavanagh M et al. A political economy of HIV treatment policy: drivers of health policy diffusion. 22nd International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2018), Amsterdam, abstract WEAD0301, 2018.

View the abstract on the conference website.