This article is also available to read in Russian.

Although well over half of new cases of HIV in the World Health Organization (WHO) European region (which includes Siberia and central Asia) occur in Russia, there is surprisingly little we know on a nationwide level about the country’s epidemic.

This is partly due to deliberate lack of transparency by Russian authorities but it is also to do with the fact that notifications of HIV cases, notifications of deaths and figures for HIV prevalence are all collected by different authorities and not collated. In addition, owing to Russia’s culture of stigma against key affected populations, comprehensive statistics on the likely route of transmission are not collected.

Now, in what its authors describe as an “exploratory and descriptive study”, figures from different agencies have been pulled together to paint a picture of HIV in this vast country.

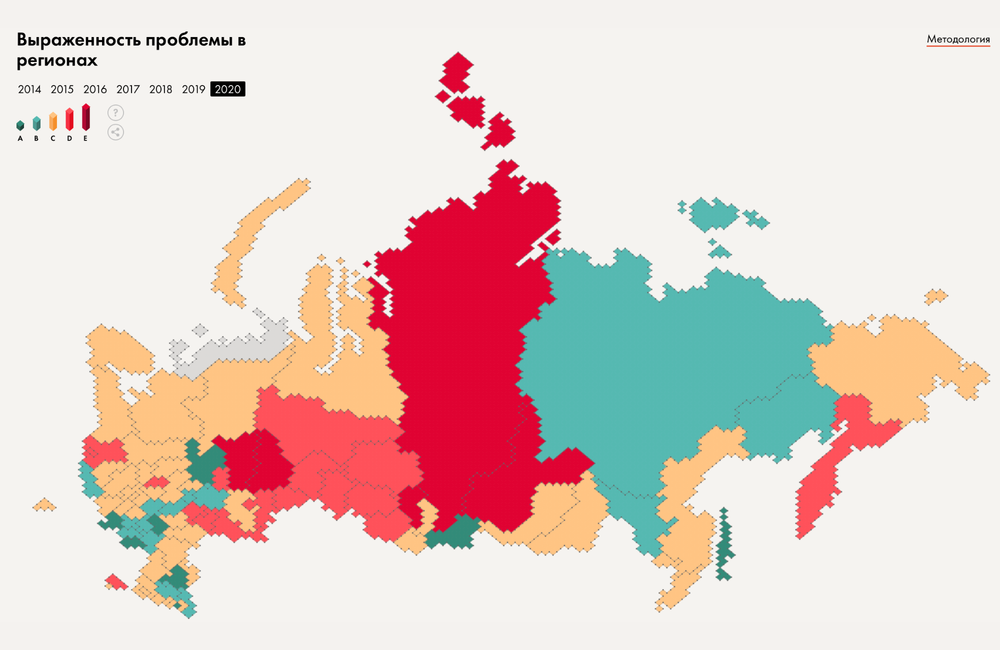

The analysis, by Dr Zlatko Nikoloski from the London School of Economics and colleagues has found huge differences in HIV deaths and HIV prevalence between different provinces in Russia, with areas with the highest HIV prevalence in the whole continent next door to areas with some of the lowest prevalence.

Figures for HIV-related deaths and HIV prevalence within regions were highly correlated, showing that when figures are available, they corroborate each other.

It also found that both HIV prevalence and deaths were correlated negatively with the provision of antiretroviral therapy (ART). Whereas in a country with good ART provision, one would expect higher levels of ART usage in areas with higher prevalence, the reverse is the case in Russia – appallingly low levels of ART provision continue to directly drive an epidemic which is still expanding.

Russia does now supply new HIV diagnosis numbers every year to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, whose latest report shows that there were 58,340 new HIV diagnoses in 2021 compared with over 48,000 in the whole of the rest of the WHO European region. This is actually an improvement from the situation six years ago, when Russia had nearly two-thirds of the HIV cases in Europe.

But because Russia only has 18% of the WHO region’s population, this amounts to nearly six times as many new diagnoses per head of population as in the rest of the region, and well over ten times the new diagnosis rate in the European Union. One in every 2475 Russians was diagnosed with HIV in 2021, compared with one in 15,536 people in the rest of the region.

The study

Dr Nikoloski took data from four additional sources to try to better understand the country’s epidemic. All provide data at the provincial (oblast) level.

- Deaths caused by HIV are reported to the Russian Fertility and Mortality database.

- HIV prevalence – the proportion of people living with HIV – is collected by the Russian Federal AIDS Centre.

- Estimated ART coverage in different regions was assessed by an NGO-led project on HIV indicators in the country.

- Data on HIV knowledge came from a large general population survey conducted by the Federal State Statistics Service in 2018. Alongside questions on other health issues, respondents were asked whether they were aware that condoms reduce the risk of HIV, knew where to get an HIV test and if they believed HIV could be passed on by sharing food utensils.

- Finally, results were also related to indicators of each province’s population structure, economic output and healthcare resources.

Mortality, prevalence and ART

The national mortality data, expressed in the annual number of deaths due to HIV per 100,000 people, showed that HIV-related mortality had increased from 0.2 deaths per 100,000 in the year 2000, almost all in men, to 18.5 per 100,000 in 2018 in men (one death per 5405 men) and 8.7 per 100,000 in women (one death in 11,494). This can be compared with one HIV-related death per 66,850 people in the UK in the same year.

But the death rate shows big inter-regional disparities. The highest HIV death rates were five times the national rate in a band of provinces in south-east and south-central Siberia, stretching from Sverdlovsk in the Ural mountains to Irkutsk which borders Lake Baikal nearly 3500km (over 2000 miles) further east.

Mortality in Kemerovo was 88.9 per 100,000 people, or one death due to HIV per year in every 1125 people. Death rates in Irkutsk, Novosibirsk (home to Siberia’s biggest city) and Sverdlovsk were one per year in every 1767, 1871 and 1976 people, respectively.

“Appallingly low levels of ART provision continue to drive an epidemic which is still expanding.”

In contrast, deaths in some regions were lower than even in the UK. Two of these actually border Irkutsk – Tuva, sandwiched between it and Mongolia, and the vast Sakha Republic, a huge swathe of eastern Siberia centred on the freezing city of Yakutsk. These are both areas with very low population densities and little urbanised industry. But that isn’t the case for Belgorod, a province bordering Ukraine, where only one HIV-related death per 77,000 people was recorded in 2018.

HIV prevalence is closely correlated with HIV deaths. In Irkutsk, nearly 2000 per 100,000 adults are living with HIV (one in 50) and the rates in Kemerovo and Sverdlovsk are almost identical. The highest prevalence, though, was recorded in Chelyabinsk, a province just south of Sverdlovsk, where 3% of the population – one in 33 people – has HIV.

This can be compared with the UK rate of about one in 400 people, as can the rates on the lowest-prevalence provinces: one in 1812 people in Tuva, and less than one in 1000 in two European Russian provinces, Kalmikia and Dagestan, both on the borders of the Caspian Sea next to Chechnya.

The correlation between HIV deaths and HIV prevalence was 0.84, which is extremely high.

Russia still has limited provision of ART, with a national average of 45% of people with HIV on ART. Rates had a moderate negative correlation (-0.45) with HIV mortality and prevalence – i.e. the lower the proportion of people with HIV taking ART, the higher the mortality and prevalence. For example, in the high prevalence provinces of south-central Siberia, and also in Chelyabinsk, between 30 and 35% of people with HIV are on ART.

Access to ART is generally higher in European Russia west of the Urals but shows wide heterogeneity. Some of the lowest rates of ART provision – between 25 and 35% – are, surprisingly, in some of the most highly populated and urbanised areas: in Novgorod and Perm, and even in St Petersburg and Moscow, both of which have levels of ART provision lower than their surrounding provinces. Provinces with the highest proportion of people with HIV on ART are right next to them, including Pskov (between St Petersburg and Estonia) and Kirov (which has a border with Perm). Both of these provinces also have notably low prevalence, with Kirov’s nearly as low as Dagestan’s.

Some other provinces have very low ART provision but with low prevalence, notably Sakha, Karelia, Murmansk and Nenetsiye, but these are Arctic regions with sparse population.

What’s driving high HIV prevalence?

The researchers also looked at what other factors, both in terms of knowledge and socioeconomic indicators, correlated with high HIV prevalence. The only factors that reached statistical significance were fewer people reporting that they knew condoms were effective in reducing the risk of HIV, a higher proportion of the population registered as injecting drug users and a higher gross regional product (GRP) per capita.

The relationship with drug use is not surprising as Russia’s epidemic was originally driven by needle-sharing, and to a certain extent still is. In 2016, however, the proportion of infections attributed to sex between men and women (48%) equalled the proportion linked to injecting drug use and has risen since. It is important, however, to emphasise that 55% of cases of HIV in Russia do not have any route of infection reported, and that the proportion of cases ascribed to sex between men is 1.5%, despite the rate of HIV diagnoses in men not reporting injecting drug use being considerably higher than the rate in women. As far back as 2011, UNAIDS reported that HIV prevalence in gay men in both Russia and Ukraine was 8%.

"These cities attract migrant workers and, with them, higher rates of female sex work, sex trafficking, and drug dependency."

But injecting drug use remains important. Russia is notorious for not allowing opioid substitute therapy (OST) for people who inject drugs, and since Russia disengaged from the Global Fund access to needle and syringe exchange programmes also decreased abruptly. Previous modelling of the epidemic in the high-prevalence cities of Omsk and Ekaterinburg estimated that starting OST and needle-exchange programmes, scaling up ART and integrating drug and HIV treatment programmes would result in the rate of new diagnoses dropping by half within ten years.

The finding on basic condom knowledge shows the need for education and prevention programmes. However, politicians and the church discourage discussion of these topics (especially for sexual minorities), while Russia has no government-sponsored condom provision.

The association with economic output is interesting. Some parts of Siberia and the Arctic have the highest GRPs in Russia, despite relative remoteness. This is because the reason there are cities at all in these areas is because they were often built around oil and gas extraction and, especially in the Urals and the Arctic, mining. These cities attract migrant workers and, with them, higher rates of female sex work, sex trafficking (often of migrants from heroin-producing countries), and drug dependency.

Bureaucracy and unintegrated systems are another reason for the lack of ART provision, which fuels the epidemic. One reason ART rates are lower in Moscow and St Petersburg, for instance, may be because internal migrants who move to the cities to find work face bureaucratic barriers to registering for medical care in their new location.

Conclusion

There have been other analyses of the Russian HIV epidemic before, but most have concentrated on specific cities and regions. This study, according to the authors, is the first time researchers have attempted to correlate HIV trends in this vast and disparate country by going to the available raw data, incomplete though it is.

The authors end on a pessimistic note, noting the social and religious attitudes in Russia that curtail effective interventions for injecting drug users, sexual minorities and other marginalised communities. “The social and political transformations underway in Russia will most likely present serious challenges in addressing the HIV epidemic,” they say.

Nikoloski Z et al. Human immunodeficiency virus in the Russian Federation: mortality, prevalence, risk factors, and current understanding of sexual transmission. AIDS 37: 637-645, 2023.

www.doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003441

Full image credit: HIV prevalence by province in Russia. Image from tochno.st/problems/hiv