There remains a substantial gap throughout Europe between the need and desire for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and the number of people actually using it, an online workshop convened towards the end of last year by the European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) heard.

The workshop on PrEP was the second part of its fourth Standard of Care meeting. This was scheduled to be last October in Tbilisi, Georgia but due to COVID-19 has been split into an opening meeting, three workshops on PrEP, COVID and ageing and a wrap-up meeting in February. Our report on the first meeting is here.

The PrEP workshop was attended by representatives from EACS, the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC), the European AIDS Treatment Group (EATG), and PrEP in Europe. It was a closed workshop and individual speakers will not be named, but representatives came from Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Italy, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine and the United Kingdom.

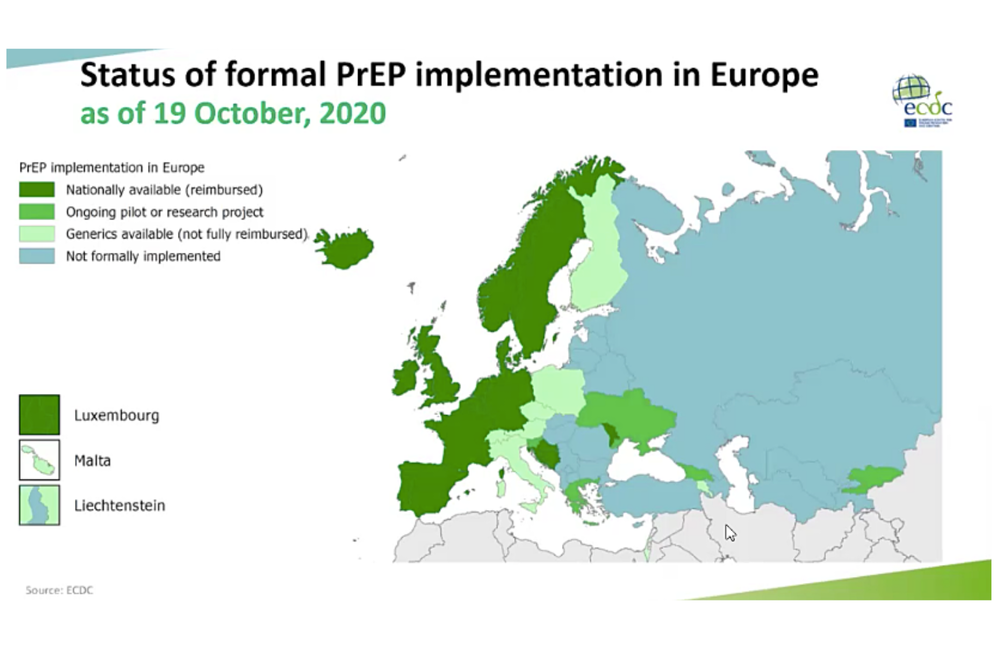

The first country to provide PrEP through its national health service was France in 2015. Now 15 countries provide it through their health service (or 18 if the devolved nations of the UK are counted separately); another five currently host demonstration trials; and in eight others, while it has to be bought online and is not reimbursed, medical monitoring is accessible via sexual health clinics or in primary care. This leaves over 20 countries where there is still no systematic provision.

The ‘PrEP gap’ between interest, need and use

ECDC has calculated that the real gap in PrEP provision is not between countries that provide it and the ones that don’t, but between the number of people whose risk factors show they need it, the number who say in surveys that they would definitely use it, and the number who actually do.

In the case of gay and bisexual men, the last European Men who have sex with men Internet Survey (EMIS) survey showed that 63% of respondents who were not diagnosed with HIV had heard of PrEP, though awareness ranged from 28% to 81% according to country. In EU/EFTA countries, 21% said they would be “very likely” to use PrEP if they knew how to get it.

However, only 3.2% of respondents actually used PrEP (the highest proportion was 9% in the UK). The average ‘PrEP gap’ between wanting PrEP and using it was 17.6%. Outside the EU/EFTA countries, in eastern Europe, the gap was bigger, with, for instance, 45% of Russian respondents to EMIS saying they would be very likely to use PrEP, but only 1% actually using it. It is estimated that there may be half a million people in Europe who would be very likely to use PrEP if it was easily accessible.

PrEP for non-gay male populations

Gay and bisexual men represent the vast majority of PrEP users. There are no equivalents to EMIS to establish awareness across Europe among other at-risk groups such as female sex workers, trans men and women, cisgender at-risk women, injecting drug users and their partners, migrants and others.

In some countries, especially in eastern and central Europe, current practice may be channelling PrEP to some people who do not need it, such as the partners of people with HIV who are stably virally suppressed. In Moldova, for instance, a small country where PrEP has been in national health guidelines for over two years, there are still only 145 people receiving it. A quarter of those are women who are mostly partners of stably virally suppressed men with HIV.

There has been little research outside Africa to establish actual need in populations like women, and in some cases, this may even be hard to measure. As one workshop attendee asked, “How do you ask women if their male partners are having sex with men that they don’t know about?”.

Providing PrEP through sexual health clinics may be one of the barriers to providing it to a more diverse population. One doctor said: “Only 20% of my cisgender women patients had ever been to a sexual health clinic before they were diagnosed with HIV. I asked all of them whether, if PrEP had been available shortly before they were diagnosed, they would have taken it; not one said they would have.” This was not so much because of stigma as because of lack of awareness of HIV being a risk for them. “Even though, objectively, if you looked at their life circumstances, you could see that many were at risk.”

A community representative said: “With cisgender women especially, HIV may not be the first sexual health issue women think about, if at all. They are probably more likely to engage the system regarding pregnancy or infertility. PrEP needs to be provided through gynaecological and family planning services if we are going to interest them in what is, for them, an additional sexual health protection mechanism.”

The IMPACT study in England included about 1250 participants who were not gay and bisexual men (split evenly between transgender and cisgender, male and female), but they only represented 5% of the total.

Demedicalisation

'Demedicalisation' was a word much used in the workshop. It was acknowledged that simply for reasons of capacity, expanding PrEP provision would be difficult if every appointment had to involve a doctor (some countries still require a doctor’s permission or presence even for an HIV test).

There was a lot of discussion about how PrEP services could be demedicalised to some extent without compromising safety. For instance, kidney function tests probably did not have to happen every three months for people aged over 45 and could be done with a urine dipstick.

But there was concern about total demedicalisation – a 'PrEP over the counter' model, as effectively already happens with unlinked online purchase. A UK doctor said that although serious adverse events were rare, there had been a few cases of pancreatitis in the IMPACT implementation study in England. If people were able to start without an HIV test, the small possibility of PrEP use during acute HIV infection giving rise to HIV resistance might become larger.

A better model might be what was called “a light-touch patient-controlled situation that gave PrEP users access to the tests they need.” In the respect COVID had been the mother of invention, forcing clinical services to adopt measures within weeks that they had been discussing for years, such as telemedicine, home testing, NGO and peer-group provision, new medication delivery systems, and so on.

Although injectable cabotegravir, which is likely to become available in a few months time, might be seen as re-medicalising PrEP – in that there will be no way of getting it other than from a clinic – it might in fact demedicalise it in terms of the patient experience, as they would only have to think about taking medication every few months instead of daily.

Joint NGO/clinic referral pathways

A non-governmental organisation (NGO) based referral system might also be the solution to getting more people who are not gay and bisexual men interested in, and using PrEP. In Ukraine, there are currently 2269 people receiving PrEP through the scheme co-ordinated by the Alliance for Public Health (APH). NGOs provide risk assessments and HIV testing for their service users, then refer those who are interested and eligible to a clinic.

Though most of those referred are gay and bisexual men with a handful of trans people, 17% fall into other classes, including 128 female sex workers (and a few of their regular partners), 73 people who inject drugs and their partners, 135 HIV-negative partners of (largely cisgender and heterosexual) people with HIV, and others.

The APH had no budget for awareness-raising or demand-creation materials. But a workshop participant from APH said that it was not particularly difficult to integrate PrEP promotion and assessment into HIV prevention and sexual health services already being provided to NGOs that work with these groups. “It just becomes something else you talk to them about.” In this way, a two-stage referral model of risk assessment by an NGO and then medical assessment (solely for contraindications and other more complex issues) by a doctor might work better.

Better assessment of who really needs PrEP, and how they use it

There is still an issue regarding cisgender women who may not fall under the remit of NGOs. Within the English IMPACT trial, some sexual health clinics ran a pilot study of a tick-box survey given out to all female attendees in the trial’s last month. This asked if there were any features in their lives that might indicate HIV risk such as unstable housing, intimate partner violence, partners from high-prevalence countries, etc. The vast majority of women answered ‘no’ to such questions, but a ‘yes’ triggered an HIV risk chat with a sexual health advisor. “We recruited as many women to the study in that month as we did in the previous 18 months,” one doctor said.

Finally, a strong plea was made by the two community representatives in the workshop for clearer results from continuing PrEP research – not so much of new drugs and formulations, but of epidemiological models and of the way people actually used PrEP in real life.

A community representative from Croatia, which has a small PrEP programme for gay and bisexual men, commented that is was not even certain if ECDC’s ‘PrEP gap’ model really reflected the true number of people who needed to be on PrEP to produce the reductions in HIV incidence demanded by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal of a 90% reduction in infections by 2030. “When I talk to some gay men who are keen to start PrEP,” they said, “You actually find out they are not having that much sex.” HIV is highly ‘nodal’ and has an even higher K number than COVID – meaning that a few people transmit HIV a lot and most transmit it rarely if not at all. There needed to be better models and indicators that could guide really effective PrEP prescription.

There has been very little research into intermittent PrEP regimens other than the 2-1-1 regimen used in the IPERGAY study. Many doctors and nurses find this regimen confusing to explain, while participants in PrEP social media groups often discuss using PrEP drugs in different and more pragmatic ways – such as using the 2-1-1 regimen essentially as PEP, taking it immediately after a risk event. Would this work? We don’t know.

Research also needs to be conducted into the way people stop PrEP, and why. At present there is not even a consistent definition for stopping PrEP, as the vast majority do not say they’ve stopped but just don’t turn up for their next appointment.

Recommendations

The meeting produced a number of recommendations and ideas to start answering some of these questions and meet these needs.

ECDC will publish an operational guidance document in the next three months, which will compare how PrEP provision has been run in different countries and issue a common set of recommended procedures and standards.

This will include a template intended for EU countries to use to standardise their responses – these have already been completed by 17 countries and will be used in the operational guidance as case studies.

The operational guidance can be used as the basis of an EACS/ECDC auditable standard of care on PrEP, and EACS is investigating this template for non-EU countries, with an eye to a possible joint ECDC/EACS publication of extended guidelines.

The EACS Standard of care page is here: www.eacsociety.org/conferences/standard-of-care-meeting/standard-of-care-for-hiv-and-coinfections-in-europe.html

The aidsmap report on the first 2020 Standard of Care meeting in Tbilisi, Georgia is here: www.aidsmap.com/news/nov-2020/european-hiv-doctors-conduct-their-first-ever-region-wide-audit-services