Even though a review of 16 studies including almost 44,000 people found that social harms associated with HIV partner notifications are rare (less than 1%), with the most common being relationships ending, researchers warn that further research is crucial to fill in the knowledge gaps they identified.

“Very few of the studies followed up index clients longer than 6 weeks after testing,” the authors write. “Future studies should assess index clients longitudinally to determine if there are any long-term risks associated with partner notification services that were not captured within the studies in this review. Additionally, legal provisions for protecting people with HIV against potential harm following partner notification systems are lacking, particularly for marginalised and criminalised populations. Furthermore, the absence of healthcare provider motivation to report social harms and absence of current structures for reporting, increase the risk that social harms will be under-reported and unaddressed.”

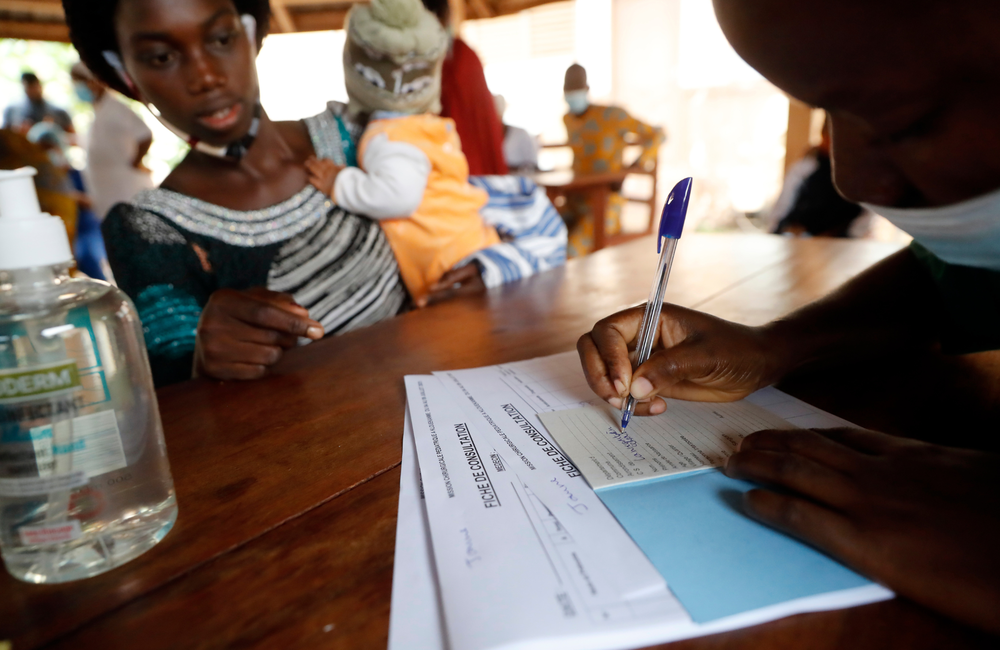

HIV partner notification – also known as contact tracing or index testing – is a voluntary approach in which a trained healthcare provider invites a person with HIV to disclose the name(s) and contact information of their sexual and/or drug-injecting partners as well as their biological children. If the person agrees, the provider and client work together to determine the most appropriate way to contact partners and offer them HIV testing.

With many governments and international agencies recommending partner notification, it is important to carefully consider the potential risks and its consequences, particularly for women, key populations, and adolescents and young women. With that in mind, Dawn Greensides and colleagues from USAID reviewed 15 articles and one conference abstract that reported data on the incidence of adverse events and social harms as a result of partner notification.

Of the 16 studies with 43,978 participants, two were focused on key populations, two on women who recently experienced intimate partner violence, two on women in antenatal care settings, one was conducted in a refugee setting, and the remaining nine were focused on the general population. All studies were conducted in Africa, except for one from Vietnam.

The range of harms reported across the studies included relationship dissolution, loss of financial support, and intimate partner violence (including physical violence, verbal abuse, threats, and sexual violence).

Among the 16 studies that examined harms, prevalence ranged from 0% to 6.3%.

- Four studies reported that no harms were experienced.

- Seven studies found that no more than 1% of people experienced harms.

- Three studies reported that between 1% and 2% experienced harms.

- Two studies reported a higher prevalence, at 4% and 6.3% respectively.

Overall, all of the studies looked at social harms resulting from the disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners. No studies identified adverse events due to the health care system not meeting minimum standards (breaches of confidentiality, coercion, withholding treatment, or unauthorized disclosure). One study reported that even though the study protocol directed healthcare providers not to contact partners if the index client had a history of intimate partner violence (IPV), several providers did so. Despite this deviation from the protocol, the absence of harms in this study is reassuring. Additionally, only one study looked at harms perpetrated not just by the sexual partner but by extended family and/or community members.

Several of the included studies mentioned a low incidence of IPV because women who experienced a higher risk of IPV were either not eligible for partner notification or likely elected not to participate. However, the exclusion of those who have reported a history of IPV is not stipulated in World Health Organization guidelines. Instead, they recommend assessing the risk of harm on a case-by-case basis in consultation with the index client.

Seven studies included index clients aged 15 years and younger and there was no distinction or consideration of rates of harms across the different age groups. However, unequal power dynamics between health care providers and young people, particularly adolescent girls and young women may lead to coercion and unsafe partner notification, and in many countries, young people aged younger than 18 years face restrictions on their decision-making. Therefore more research is needed on partner notification in this age group.

Very few of the studies followed up index clients longer than six weeks after testing. Two studies followed up index clients for longer, but only discussed harms reported at the six-week follow-up.

Another critical knowledge gap was healthcare worker capacity. This was highlighted in a qualitative study in Kenya in which female participants reported inadequate discussion by providers – or no discussion at all – about negative outcomes, particularly the risk of partner violence. In addition, the women reported receiving only “broad” advice from providers on how to disclose to partners safely. Most notably, those who experienced abuse from partners after disclosure said that they had received no counselling on how to disclose HIV status safely and no information on the risks of IPV after disclosure. For safe partner notification, health providers must be well-trained, sensitised, and able to clearly and consistently discuss the risks, even when partner confidentiality is maintained.

The International Community of Women Living with HIV Eastern Africa recently published a policy brief calling on PEPFAR to stop partner notification for women and young women living with HIV, just as they did for sex workers, men who have sex with men and other key populations, until PEPFAR provides guidance on minimum standards and processes. These are required to ensure that facilities are capable of implementing partner notification in a confidentiual and voluntary manner, with informed consent.

“Assisted Partner Notification has been poorly implemented; moreover, in an aggressive manner," say the authors. "Women and young women living with HIV complain that they are being coerced to give their partners contact details and not respected by the health workers. The contact details are then used to disclose their sexual partners' status. It has caused mistrust between the health workers and young women and women living with HIV because it has undermined their rights to consent, privacy, confidentiality and safety."

They note that in Kenya in 2019, three cases were reported in the media of young women living with HIV who were killed because their partners knew their status through other sources other than the women themselves.

All programmes continuing to implement index testing should apply a client-centred approach, which clearly states that index clients are not required to provide names of sexual contacts, and people should always be counselled about the benefits and risks so that they can make safe and informed choices, they conclude.

Greensides D et al. Do no harm: a review of social harms associated with HIV partner notification. Global Health: Science and Practice 11(6):e2300189, 2023 (open access).