A Danish study of healthcare costs between 2006 and 2017 has found that the combined costs of treating mental illness and non-communicable diseases (such as heart disease and kidney disease) among people living with HIV were almost double the cost of treating HIV itself. Healthcare expenditure is also considerably higher for people living with HIV compared to HIV-negative people even after excluding the costs of HIV care, according to the study published in HIV Medicine.

The study has some important limitations, including not adjusting for differences in income, marital status, ethnicity, sexual orientation, social class, housing, employment, or health information such as HIV treatment duration and whether an individual smoked or used drugs. These factors likely explain much of the difference in healthcare costs between participants living with HIV and HIV-negative participants. Nevertheless, the authors argue that their findings support taking a patient-centred approach to HIV treatment which focuses “on the whole patient presenting with a variety of health problems due to non-communicable diseases”.

Understanding how healthcare budgets are being spent can help to better plan and prioritise healthcare services, thereby improving health outcomes for individuals and reducing the cost of their care. Previous research has generally focused on the direct costs of treating HIV but hasn’t included the additional costs of treating other health conditions that people living with HIV may have. Consequently, a team of researchers led by Dr Lars Holger Ehlers of the Nordic Institute of Health Economics designed a study which could estimate the economic cost of non-communicable diseases and HIV care in people living with HIV in Denmark.

The study population included all people living with HIV in central Denmark who were diagnosed between 2006 and 2017 and matched them with HIV-negative individuals from the general population. Data on health service use and costs were collected from a range of national health and HIV-specific databases. This included data on all inpatient and outpatient visits to Danish hospitals for non-communicable diseases and mental health, medicines prescribed for common health conditions (for example, statins), and all visits to primary care. Costs were adjusted for inflation to the 2019 price level.

Who was included in the study?

Data came from 407 people living with HIV and 4070 people without HIV.

The median age at the time of HIV diagnosis was 39.5 years old; 71.3% were men. As each participant living with HIV was paired with ten HIV-negative individuals born in the same year, of the same sex, and residing in the same municipality at the time of HIV diagnosis, the HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups were identical in these respects. All healthcare in Denmark, including HIV treatment, is free-of-charge for residents so neither group faced financial barriers to healthcare.

Participants living with HIV were less likely to be born in western Europe compared to participants without HIV (67% vs 91%, respectively). They also had lower average incomes (€29,172 vs €43,088), were less likely to have gone to university (23% vs 32%) and were more likely to have two or more other health conditions (9.3% vs 5.6%) before being diagnosed with HIV.

How did healthcare costs differ for the participants living with HIV?

Participants living with HIV had consistently higher healthcare costs before and after being diagnosed with HIV, compared to the people without HIV. On average, the total healthcare cost per person living with HIV during the study period was more than three times higher than for those without HIV (€6350 vs €1974). When the cost of HIV care was excluded, average healthcare costs per person were still more than double for people living with HIV than people without HIV (€4174 vs. €1974). These additional costs were largely down to the treatment of non-communicable diseases and mental illness.

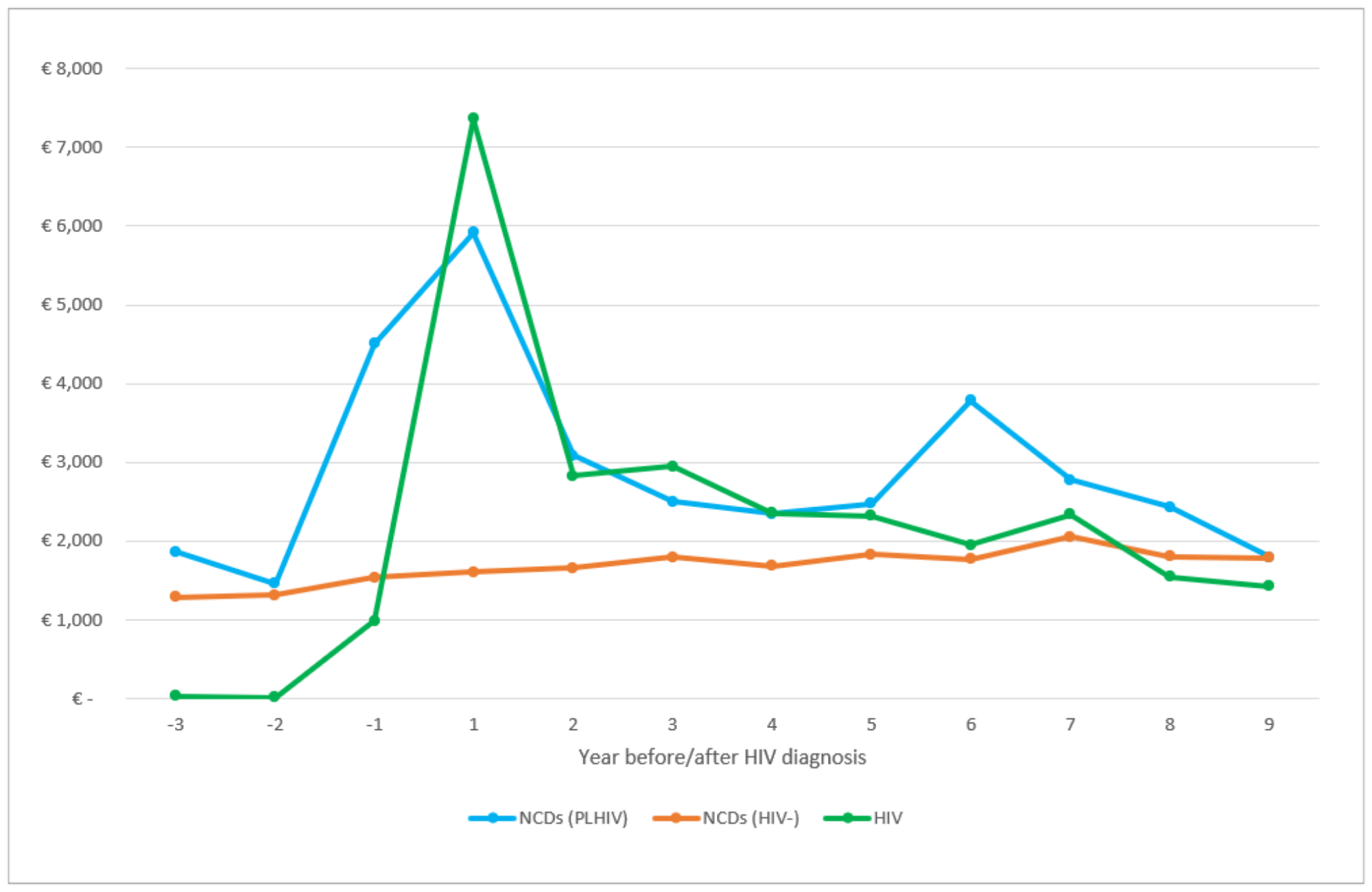

The figures below show how the yearly costs of healthcare changed over time for people living with HIV and HIV-negative people. The first compares expenditure on HIV treatment and care with expenditure on non-communicable diseases in people living with HIV and people without HIV. The second does the same but with expenditure on HIV and mental health treatment and care.

In the years before HIV diagnosis, mental health expenditure was higher for people living with HIV than for people without HIV. Costs of treating non-communicable diseases started to increase in the year prior to HIV diagnosis. This could indicate that people are being diagnosed late once HIV has already started to affect their immune system.

Understandably, healthcare costs spiked around the time of HIV diagnosis. As well as the costs of treating HIV and the consequences of late diagnosis, people recently diagnosed with HIV may need mental health support to adjust to their diagnosis. Increased engagement in healthcare at the time of HIV diagnosis may also have led to diagnosis of non-communicable diseases that might otherwise not have been picked up until later.

In the years after HIV diagnosis, the cost of treating non-communicable diseases was higher for people living with HIV compared to people without HIV. The cost of treating HIV declined over time, which the authors suspect is largely due to the introduction of generic HIV treatment in 2013. Conversely, the treatment costs for non-communicable diseases and mental illness increased over time.

Notably, the combined costs of treating non-communicable diseases and mental illness among people living with HIV were consistently higher than the cost of treating HIV throughout the study.

What are the implications of these findings?

The study findings indicate that healthcare costs for people living with HIV in Denmark are substantially higher than previous estimates. The authors propose a number of reasons why this might be the case.

Firstly, the study is the first to examine individual-level patient register data from such a lengthy time period. Danish health databases are unusually comprehensive and regularly updated, meaning that the findings are potentially more reliable than modelled estimates.

However, there were also some important differences between the participants living with HIV and those who were not that are likely to have influenced the difference in healthcare costs. The higher proportion of migrants among the participants living with HIV reflects the epidemiology of HIV in Denmark, with migrants disproportionately affected by HIV. Migrants are also more likely to be diagnosed late in Denmark (and elsewhere in Europe), for a range of reasons including unfamiliarity with the healthcare system, fear and/or experience of discrimination, and difficulties communicating with health providers.

The study did not control for differences in income or marital status. Both these factors can have a significant influence on health. One study found that refugees were less likely to have multiple health conditions compared to people born in Denmark once income and marital status were taken into account, yet the reverse was true before adjusting for these factors. Social class, housing, and employment are also important determinants of health, and these were not controlled for.

The study also did not control for sexual orientation and ethnicity, yet LGBT people and certain minoritised ethnic groups are disproportionately affected by HIV and often experience poorer health outcomes (especially in mental health) due to societal marginalisation. It also lacked other health information such as how quickly someone received HIV treatment after diagnosis, or whether an individual smoked or used drugs.

For these reasons, the study authors did not attempt to model costs or determine cost-effectiveness. However, their findings may still have some practical implications for the organisation of healthcare systems. In Denmark, people receive HIV care in public hospital clinics specialised in HIV. This study indicates that care which focuses on the whole patient, with greater involvement from non-communicable disease specialists, may help to improve health outcomes and reduce costs in the longer-term. Increasing access to HIV testing, particularly for migrants, could also help to reduce late diagnosis.

Ehlers LH et al. Cost of non-communicable diseases in people living with HIV in the Central Denmark Region. HIV Medicine, online ahead of print, 23 October 2022 (open access).

doi:10.1111/hiv.13414