An injection every two months of the antiretroviral cabotegravir is the most effective way to prevent HIV that the world has ever seen. Making it affordable will depend, in part, on how many generic manufacturers will invest in producing it — and for that, the world must show the promise of markets: millions of otherwise healthy people who will line up at a pharmacy or clinic for a quick injection every two months.

The question is: how do you create a market for a product that most of the world has not yet seen?

Two large-scale clinical trials conducted among gay and bisexual men, transgender women and cisgender women found that those who received injections of the antiretroviral cabotegravir were about 80% less likely to contract HIV than those taking the daily HIV prevention pill. This is probably because it is easier to use than daily medication, the World Health Organization explains in new guidelines on the injection’s use.

Rapidly rolling out the injection in sub-Saharan Africa could lead to a 27% reduction in new cases in the region in the next roughly 50 years, according to the preliminary results of unpublished mathematical modelling quoted in presentations this week at the 24th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2022). The study, which has been submitted to The Lancet, showed widespread access to long-acting HIV prevention injections could save about 75,000 lives annually by 2070.

Although ViiV Healthcare, which developed the injection, is working to encourage generic manufacturing, it is likely to be the sole producer for the next three to five years. The official price tag in the only country in which it is currently approved for use — the United States — is $22,000 per person annually. Still, if pricing trends around other antiretrovirals are any indication, official prices will be lower even in other high-income countries and many payers will negotiate substantial discounts.

ViiV has already committed to registering and supplying injectable cabotegravir to the 14 countries that were involved in clinical trials. Nearly half of these were in sub-Saharan Africa. But to supply the world with the HIV prevention injection, ViiV will have to ramp up production.

"ViiV has a very robust supply chain and we’ll be expanding our volume production over time. We’re open to discussing with any government that wants to procure long-acting cabotegravir for PrEP," a ViiV spokesperson said. "However, one of the big challenges for us with supply at the moment is that demand for long-acting cabotegravir for PrEP is very uncertain.”

For ViiV to invest in expensive additional capacity in the short and medium term, it will probably need upfront commitments to purchase from large donors such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria and the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). They may get similar promises from social investment funds such as MedAccess, much like they did to introduce better malaria-busting bed nets, explains Mitchell Warren, executive director of the HIV prevention organisation AVAC.

Finally, the market will have to grow large enough to accommodate at least three additional generic suppliers that will be ready to distribute their products in around five years. But in five years’ time, an experimental, twice-a-year HIV prevention injectable called lenacapavir might also be coming to market, possibly unseating cabotegravir or reducing the market for generic versions of it.

“What if you invest tens of millions of dollars and begin to see this low-price cabotegravir coming off the line — and all of a sudden, lenacapavir shows safety and efficacy?” Warren asks.

“It’s a risk.”

It’s also why he says the quest for access to an HIV prevention injection can’t just be about cabotegravir.

New voluntary licence could be expanded

On Thursday, ViiV Healthcare announced that it had signed a voluntary licence with the Medicines Patent Pool to allow 90 low- and lower middle-income and all African countries except Libya to access generic versions of the drug. The Medicines Patent Pool is a UN-backed public health organisation to improve access to affordable, quality-assured versions of priority medicines in low- and middle-income countries through the sharing of licences.

It however excludes Brazil, for instance, which took part in clinical trials. Russia, home to more than one million people living with HIV, is also excluded as are many eastern European countries such as Albania, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan. Ukraine is included in the deal but the war-torn country will be among the ten countries that will pay ViiV royalties totalling 5% of net sales to public sector HIV programmes.

In contrast, there are about 30 countries in which ViiV has not patented the HIV prevention injection, including Thailand, Argentina, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic. In theory, future generic producers of injectable PrEP could choose to sell to these countries. However about half are small island nations with small markets that continue to face challenges in timely access to medicines partly for this reason.

As part of the licence, just three generic producers will be able to manufacture ViiV’s injection. Although this has been criticised as a limitation of the agreement, Medicines Patent Pool head of policy Esteban Burrone says the decision is part of a careful balancing act.

“We need the manufacturers who apply and get the licence to make significant investments with a very uncertain market at the end of that investment for five years,” Barrone explains.

“We're trying to balance out the need, on the one hand, for competition in the market — because that plays a significant role in keeping prices to affordable levels,” he continued. “At the same time, we want to prevent a situation that will crowd out the manufacturers.”

Burrone adds that the Medicines Patent Pool and ViiV can choose to expand the pool of generic producers if needed.

Generic producers will also be considering the potential size of the market. While about 2.8 million people have started oral PrEP in the last decade, manufacturers may need a much larger market to make it worth their while.

“We know a lot of those people had one bottle of pills and never went back again,” Warren says.

“If we took the ‘worst-case scenario’ and modelled demand for injectable cabotegravir on that for oral PrEP, you wouldn't support any manufacturing.”

Cost: is $60 per patient per year the magic number?

Until generic manufacturers are ready, ViiV will be the sole manufacturer. The company has announced it will offer the 90 countries covered in the Medicines Patent Pool licence an as yet undisclosed reduced price on the injection. ViiV says they will not make a profit on these sales.

Several sources tell aidsmap that ViiV Healthcare has discussed a potentially reduced price in these countries of $240 per person annually — nearly five times the cost of generic versions of the HIV prevention pill.

AVAC is the secretariat for a new coalition of global health partners hoping to speed up access to long-acting HIV prevention options — not just cabotegravir. The coalition includes medicine financing mechanism Unitaid, the World Health Organization, the Global Fund and, most recently, PEPFAR.

Warren says that even with conservative estimates of early demand for injectable cabotegravir, there are indications that ViiV could deliver the injection at about $120 per person per year.

Global health organisation the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) has estimated that the HIV prevention injection could be produced for about $16 per person per year – less than the price of more commonly used PrEP tablets. But ViiV says CHAI’s projections vastly underestimate the cost of making injectable PrEP – a much more challenging product to manufacture. "It's not realistic to suggest it can be made for less than generic oral PrEP, which is a simple white tablet," a spokesperson said.

UNAIDS and many advocacy organisations such as South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign and Health GAP have publicly demanded ViiV drop its discounted price to about $60 per person annually. PEPFAR was also reported to have been seeking a similar price but US Global AIDS Coordinator John Nkengasong declined to confirm this when asked by aidsmap.

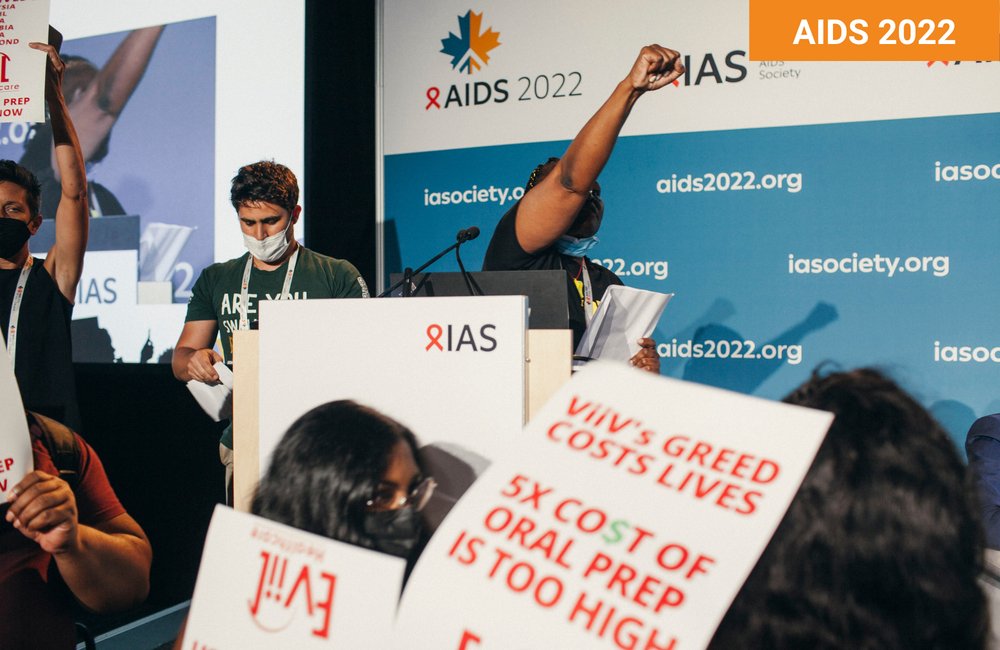

“Long-acting injectable PrEP is a game-changing revolutionary tool for HIV prevention but WHO guidelines for rolling out long-acting cabotegravir mean nothing as long as communities can’t get this product because of ViiV greed,” said Sibongile Tshabalala, chairperson of South Africa’s HIV advocacy group, Treatment Action Campaign. She was one of dozens of protestors who stormed a conference session to protest the lack of access to injectable PrEP.

Pricing is less clear for countries not included in ViiV's deal with the Medicines Patent Pool. Mitchell Warren believes countries outside the deal can expect to see tiered pricing, meaning countries would pay different prices depending on their perceived ability to pay. Upper middle-income countries outside of Africa would probably be asked to pay more than $240, but it is unlikely that prices would reach the official US price tag.

ViiV prioritises regulatory approval in trial countries

ViiV has already applied for regulatory approval for the HIV prevention injection in Brazil, South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Kenya, and Uganda. These countries all took part in the studies for injectable cabotegravir.

Researchers will be following participants in the open-label phase of these trials for up to two years. After this, ViiV will continue to provide the injection for any trial participant who wants it until the drug is registered for use in the country, a company spokesperson confirmed to aidsmap. Just how the company does this will vary by country according to local laws, infrastructure and supply chains.

ViiV has also registered the injection for use in Australia and is hoping authorisation there will help facilitate access in Asian countries that use Australian approvals to fast-track local approval, Warren explains.

Christine Malati is a senior pharmacist for the United States Agency for Development. Malati says national AIDS councils in countries in which ViiV has not yet applied for regulatory approval should begin lobbying drug regulators now for waivers to ensure timely access.

“I can imagine that over the next three years, we will see more cabotegravir PrEP users in low- and middle-income countries than anywhere else for a number of reasons,” says Warren. “That's the COVID-19 [vaccine] experience flipped.”

Cabotegravir is only the start

In a recent WHO survey of about 900 international PrEP providers, about seven out of ten said they would offer the HIV prevention injection if they had access to it.

But only about half knew that one existed.

The fight for affordable injectable PrEP is what Warren calls a “chicken and egg situation”. There’s no easy answer for how to build a market to entice investment without a product in people’s hands – or, in this case, backsides.

“It's a huge puzzle and I wish it were just one of those puzzles for a three-year-old, where it's four pieces, and one of them was the price,” he says, “But it’s a 1000-piece puzzle and it’s like every piece looks the same.”

There will be other puzzles in the future. Four new forms of long-acting injectable PrEP or implants are in clinical trials and almost twice as many are in laboratory testing.

“This is not just for cabotegravir,” Warren explains. “It’s about building what I kind of think of as prevention pipes through which we can flow anything.”

He continues: “We could imagine that these programmes that we will have strategically built for cabotegravir, we could add future injectable options — and we could go even faster.”

Advocates say that there is an urgent need for access to effective prevention tools.

“When I got HIV, I was a young girl and there were limited options,” Lillian Mworeko told a room full of delegates at the conference. Mworeko is the executive director and founding member of the International Community of Women living with HIV in Eastern Africa. “Then you people here in this room and those who are in boardrooms making decisions and policies, you told us things and we did them.”

“You said, ‘Don’t get pregnant.’ We did not get pregnant. Then you bought us prevention of mother-to-child transmission services and you said, ‘get babies,’” she continued. “We got babies and we did everything to keep them HIV negative.”

“Today these children are at the age where some of us got infected and we don’t have tools for them,” she said. “We cannot talk about access in five years.”

Update: A previous version of this article included incorrect information about the market size assumed in the Clinton Health Access Initiative's price estimates. The article was amended on 4 August 2022 to remove this.