Long COVID

‘Long COVID’ is the label given to a range of symptoms that linger or appear after an acute episode of COVID-19. The most common long COVID symptoms are fatigue, weakness, joint and muscle pain, loss of smell, shortness of breath, cognitive dysfunction, and loss of concentration.

As we first reported in March 2022, studies suggest that long COVID is more common in people with HIV. The largest study yet has recently been released, looking at over three million people who had COVID-19 in the US, including just under 30,000 who were living with HIV.

The study found that people with HIV were approximately 30-80% more likely to experience the persistence of several COVID-related symptoms, including cough, shortness of breath, headache, fatigue, diarrhoea, constipation, cognitive impairment, and body aches. Long COVID was much more common among people with HIV who first had COVID before the emergence of the Delta variant in July 2021.

The researchers also looked at serious illnesses experienced after COVID infection. These events were much less common, but new diagnoses of diabetes, heart disease, blood clots and cancer were seen more frequently in people with HIV than other people.

Although the risk of these symptoms and illnesses was higher in people with HIV, there was no link between CD4 count or viral load and risk. People who had been vaccinated against COVID were 40-50% less likely to have persistent symptoms.

Scientists are trying to understand why people with HIV appear to be at higher risk of persistent symptoms and serious post-COVID events. They are especially interested in whether HIV-related biological mechanisms play a role.

They also say that long COVID symptoms in people with HIV need to be thoroughly investigated to rule out other causes, including antiretroviral side effects, existing health conditions, mental health, and social issues.

What happens to HIV drugs in the body and missed doses

Antiretroviral therapy has completely transformed HIV into an easily manageable condition for many people. However, if you are living with HIV, you need to take your medication as prescribed in order to fully control the virus and prevent it from damaging your health.

What does happen to HIV drugs in the body? And do missed doses of HIV treatment matter? Find out in our new page.

New cancer treatments

Cancer treatment used to be mostly based on chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery. In recent years, cancer treatment has changed a lot and some of the newer treatments are safer and more effective. Newer treatments include targeted therapies and immune-based therapies that help the immune system fight cancer.

But people living with HIV have been excluded from the key clinical trials of these new treatments, leaving clinicians uncertain about whether they are safe and effective for HIV-positive people. Because people with HIV may have impaired immune function, experts have been concerned that they might not respond as well or might experience harmful side effects.

The most widely used type of immunotherapy are called immune checkpoint inhibitors. They affect a type of immune system cell called a lymphocyte. When they are active, lymphocytes can attack another cell such as a cancer cell. However, they can be switched off (deactivated) by other cells in the body. This means they are no longer able to attack cancer cells.

Checkpoint inhibitors block the signals that switch off lymphocytes. They do this by attaching to either the cancer cell or the lymphocyte. This means the lymphocyte stays active and can attack the cancer cell.

In a new study, researchers collected data on 390 people living with HIV who had used an immune checkpoint inhibitor to treat lung cancer, liver cancer, a head and neck cancer, anal cancer, skin cancer or Kaposi's sarcoma. They found that the proportion of people getting benefit from the treatment was similar to that seen in studies of people who don’t have HIV. This varied depending on the type of cancer.

Because these drugs restore immune responses against cancer, there is concern that they might also unleash the immune system more broadly, leading to inflammation throughout the body and unpleasant side effects. Reassuringly, about 20% experienced immune-related adverse events, similar to the rate for people without HIV.

Experts say that if people with HIV have cancer, it should usually be treated in the same way as for other people – although the type of HIV medication taken may need to be changed. And people with well-controlled HIV should be included in future clinical trials of new cancer treatments.

Health & Power

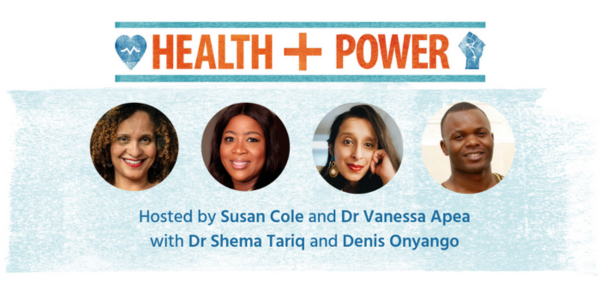

Last week, we broadcast our June episode of Health & Power, our series for people of colour focusing on health inequalities.

NAM aidsmap's Susan Cole and Dr Vanessa Apea from Barts Health NHS Trust spoke to Dr Shema Tariq from the UCL Institute for Global Health about inequalities in menopause care, and to Denis Onyango from Africa Advocacy Foundation about the impact of racism on the health of migrants.

Testing for drug-gene interactions

Each person’s genetic make-up is unique, which means that we each have different responses to drugs and medications. Every drug follows a specific pathway of absorption and elimination, and it is mostly our genes that control the speed of each step in this process. Some people’s bodies eliminate a given drug from their system more quickly which can eventually lead to ineffectively low concentrations. Other people clear drugs more slowly and are more likely to experience side effects.

US researchers provided testing for genetic variants to 96 people taking HIV treatment. Pharmacists, clinicians, and patients then reviewed the test results to identify interactions that could explain past treatment failures and side effects and identify concerns about the treatment that was currently being taken.

Sixty-five people received clinical recommendations based on their current medications – often to have extra tests or monitoring, and occasionally to change treatment. These were more likely to relate to non-HIV medications such as antidepressants than to HIV medications. Older people – who were probably taking a larger number of medications – were more likely to have problems flagged.

Using antibiotics to prevent STIs

Are you considering using antibiotics to prevent STIs? Or maybe this is already part of your sexual health routine.

Our updated page presents some of the research that has been done and the potential pros and cons of this approach.

Editors' picks from other sources

Mpox vaccinations extended in London following recent spike in cases | UK Health Security Agency

Vaccinations against mpox are to be extended in London following a recent cluster of cases, with most in those who had not been vaccinated.

New York State lawmakers pass LGBTQ and HIV long-term care residents’ bill of rights | Gay City News

The bill bars discrimination against potential care facility residents based on actual or perceived sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or HIV status.

New Terry Higgins portrait unveiled by National Portrait Gallery | Terrence Higgins Trust

The National Portrait Gallery has announced its commission of a posthumous portrait of Terry Higgins, one of the first people in the UK to die of an AIDS-related illness. 'Terry Higgins – Three Ages of Terry (2023)' is drawn in coloured pencil by artist Curtis Holder.