Stigma and quality of life

An unusually large and comprehensive survey of the experiences of people living with HIV in England, Scotland and Wales has just been published. In total, 4540 people filled in the Positive Voices survey, which represents approximately one in 20 of people (4.4%) attending HIV clinics in the three countries.

Despite satisfaction with HIV care, the findings highlight that an HIV-positive diagnosis continues to be a source of isolation and stigma, especially among trans people, younger people and women.

Almost everyone taking part was on HIV treatment and 92% said they were ‘very satisfied’ or ‘satisfied’ with their current HIV treatment plan. High adherence led to 92% reporting having an undetectable viral load, which means they were unable to transmit HIV sexually. Over 90% of respondents stated they knew of ‘Undetectable equals Untransmittable’ (U=U).

But confidence in U=U was lower, varying significantly by demographic groups. When asked if they believed the U=U statement was true, 73% of gay and bisexual men, 56% of heterosexual men, 53% of Black Africans and 51% of women said they believed the statement, with older people less likely to believe it. Three in five people stated that knowing about U=U reduced their self-stigma, but this was more true for gay and bisexual men than for other groups.

When it came to sharing their status with other people, half had told one or more of their current sexual partners. More generally, only 1 in 8 had shared their status with most people in their lives and 1 in 10 had not told anybody apart from healthcare staff.

When asked to score their life satisfaction on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 was “not satisfied at all” and 10 was “completely satisfied” the average score was 7.3 (compared to 7.5 in the general population). While satisfaction levels increased with age and were higher among Black Africans and women, they were generally similar across different demographics except for trans and gender diverse respondents who had the lowest scores (5.7 out of 10).

But almost half (45%) said they felt ashamed about their HIV status; this was higher among young people (54%), heterosexual adults (48%) and gender diverse people (48%). A third stated they had low self-esteem due to their HIV status. Also, 4% reported being verbally abused due to their HIV status and 3% reported feeling excluded from family activities.

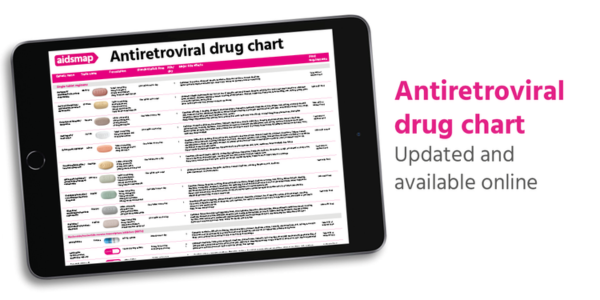

Antiretroviral drug chart

We have published a new edition of our Antiretroviral drug chart. The chart is a one-page reference guide to all the anti-HIV drugs licensed for use in the UK or European Union, with information on formulation, dosing, key side effects and food requirements.

For clinics that are members of our patient information subscription scheme, printed editions of the chart will be available to order on the clinic portal at the end of the month.

Undetectable viral load

A group of US doctors have suggested that the way viral load results are communicated should be changed. They say that the way results are sometimes given now can be confusing and can sometimes cause distress.

This is because the tests used are able to detect minute quantities of the virus, including tiny quantities that make no difference to the risk of passing on HIV during sex. The key studies on viral load and sexual transmission of HIV all used a threshold of 200 copies/ml – no one with a viral load below this level passed on HIV. And while we talk about ‘undetectable’ viral load, modern lab tests are in fact capable of detecting smaller quantities of virus.

For example, a test may have a “lower limit of detection” of 40 copies/ml. While one person’s test result might be “not detected”, another person’s viral load might be reported as “HIV detected, <40 copies/ml”. This indicates that the test picked up a tiny trace of HIV (less than 40 copies/ml) but this was too small for the test to give an accurate estimate of the number of copies. Someone else’s result might include a precise figure, such as 120 copies/ml.

In all these cases, as long as the number of copies is 200 or less, the viral load is low enough to be considered ‘undetectable’ and there is zero risk of HIV transmission during sex.

Given the confusion this sometimes causes, the doctors suggest that one option would be for laboratory reports to include the words “no risk of sexual transmission” when viral load is below 200 copies/ml. Alternatively, all viral loads below this level could be automatically reported as “undetectable”, with the precise value hidden but available to clinicians to disclose with further explanation if needed.

They also say that healthcare providers should spend more time ensuring that people with HIV understand that the term ‘undetectable’ refers to any viral load below 200 copies/ml.

Health & Power

On Monday evening, we broadcast the final episode of Health & Power, our series for people of colour focusing on health inequalities. NAM aidsmap's Susan Cole and Dr Vanessa Apea spoke with Professor Samuel Seidu from the University of Leicester and Rianna Raymond-Williams from the Impact on Urban Health, who is also a PhD student in sexual health. The focus this episode was on diabetes and sexual health.

Limited treatment options

In a large study of people living with HIV in Europe, Australia, Argentina and Israel, one in ten people had limited treatment options – which means that they could no longer take a standard three-drug antiretroviral combination.

Of 26,621 people with HIV, 1437 already had limited treatment options before the study began and another 2164 people started to have limited treatment options during the course of the five-year study.

Running out of treatment options is often understood as being linked to a person’s virus becoming resistant to some widely used drugs and the treatment failing. But this was the case for only a quarter of those who started to have limited treatment options.

It was more common for people to have stopped their previous HIV medications because they couldn’t tolerate them (54% of new cases). This shows that new HIV medications are needed not only because of drug resistance, but also because co-morbidities among people with HIV mean that some antiretrovirals are either poorly tolerated or are unsuitable for use by people with multiple health conditions.

Why is HIV hard to cure?

We know that HIV infection can be cured but, so far, cures have only been confirmed in a handful of cases.

Find out why a cure is so difficult and the two main ways HIV cures have been achieved in our new page.

Editors' picks from other sources

UK: DVLA updates its HIV guidance for drivers | Terrence Higgins Trust (THT)

THT has worked with the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) to make their guidance clearer and to ensure that the DVLA requirements for driver licensing are accurate, medically necessary and don’t perpetuate HIV-related stigma.

People born with HIV: we are lifetime survivors | POZ

People born with HIV are reclaiming their experiences – and giving themselves a new name.

Could an HIV cure be based on the same breakthrough as the new treatment for sickle cell? | TheBody

Could the revolutionary advance of CRISPR hold the key to an HIV cure? That’s exactly what a San Francisco-based company called Excision Biotherapeutics is trying to find out.