Searching for an explanation of weight gain on HIV treatment

Andrew Hill presenting at EACS 2019. Image: @andreaantinori

There was standing room only at the session on weight gain in people taking HIV treatment at the 17th European AIDS Conference (EACS 2019) yesterday in Basel, Switzerland.

Weight gain associated with dolutegravir has been flagged up in the past two years, but the issue appears to be associated with a wider range of antiretrovirals. Weight gain on modern antiretroviral treatment consists of general fat gain – both subcutaneous and central fat – with an increase in waist circumference. It is not the same as the fat redistribution syndrome (lipodystrophy) that was observed two decades ago.

Dr Andrew Hill of the University of Liverpool told the conference that weight gain after starting antiretroviral treatment is partly a 'return to health' effect in people who start treatment with low CD4 cell counts and/or high viral load, but that it does appear to be strongly linked to specific drugs. Moreover, there appear to be additive effects with specific combinations of drugs.

The integrase inhibitors dolutegravir and bictegravir are associated with the greatest gains in weight. The older formulation of tenofovir (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; TDF) is consistently associated with less weight gain than the newer formulation of tenofovir (tenofovir alafenamide; TAF) or to abacavir. Weight gain has also been observed with the NNRTI rilpivirine.

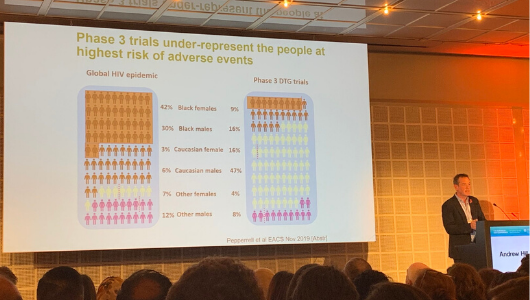

Complicating the search for a cause, the greatest gains in weight have been observed in women and black people, who are under-represented in clinical trials of new drugs. The impact of genetics on metabolism of drugs might explain differences in weight gain. Although some studies show little weight gain after switching to an integrase inhibitor-containing regimen, white men have been over-represented in these studies.

Whereas the TAF formulation of tenofovir is associated with a lower risk of bone fractures and kidney failure than the older formulation TDF, this needs to balanced against the higher risk of clinical obesity seen with TAF – and its potential impact on cardiovascular disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, adverse birth outcomes and diabetes, Hill argued.

Metabolic syndrome as well as weight gain

Michelle Moorhouse presenting at EACS 2019. Image: @andreaantinori

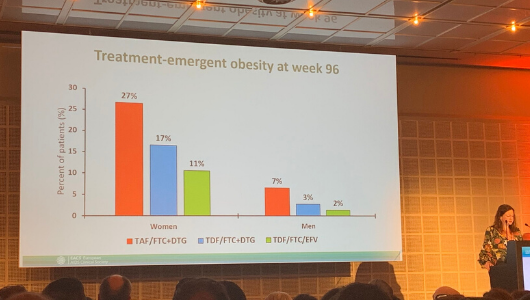

One of the key studies to have highlighted weight gain is ADVANCE, a randomised control trial designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of dolutegravir and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) in South Africa. At EACS, Dr Michelle Moorhouse of Ezintsha reported more detailed 96-week results from the trial.

The most pronounced gains in weight occurred in those receiving a combination of dolutegravir, TAF and emtricitabine – a mean gain of 6kg in men and 9kg in women. The majority of this was fat, evenly split between limb and trunk fat. More than 20% of women randomised to this combination were newly obese by week 96.

Moreover, metabolic syndrome occurred more frequently in individuals randomised to receive this combination. Metabolic syndrome was defined as obesity plus any two of elevated triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol, raised blood pressure, elevated glucose, or treatment for any of those. It was observed in 9% of those on dolutegravir/TAF/emtricitabine, compared to 5% of those taking dolutegravir/TDF (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate)/emtricitabine or 3% receiving efavirenz/TDF/emtricitabine.

Some researchers have suggested that the reason for greater weight gain on newer regimens, is because they have fewer gastrointestinal side effects, leading to better food absorption and appetite. However, an analysis which excluded people reporting those side effects demonstrated that tolerability does not explain the difference in weight gain.

HIV-positive rugby player challenging stigma

Gareth Thomas at EACS 2019. Image: Sven Huebner

He spoke of his shame and regret after learning of his HIV diagnosis, “and a horrible sense of isolation – the sense of shame grew every day”, he said, as he realised that he could not be honest with family, friends and colleagues.

He decided to make a BBC television documentary to educate the public. “I wanted to challenge stigma head on,” he said. “I wanted people to see that I was capable of swimming two-and-a-half miles in the sea, cycling 112 miles and running a marathon with HIV. If I can do that, we can do anything.

“That day we took a small step towards educating, and breaking stigma. Also, on that day, I took a road that I’d spent many years trying to avoid, only to realise that it was probably the road to my destiny.”

Professor Chloe Orkin of the British HIV Association said: "He has made such a difference to my patients. They tell me all the time how he has empowered them to talk about HIV."

90-90-90 progress but a stark gap between east and west

Anastasia Pharris of ECDC at EACS 2019. Image: Gus Cairns

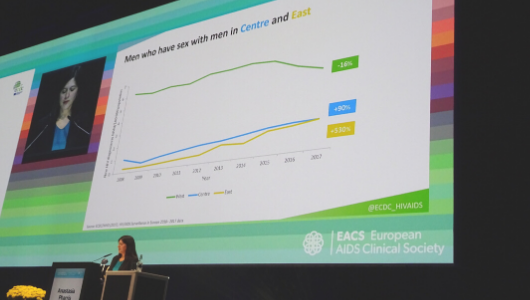

In terms of the first target (90% of people with HIV to be diagnosed), around 80% of people living with HIV in the European region know their status. More than half of European countries have already met, or are close to meeting, this target. However, late diagnosis is a problem throughout the region, with half of people being diagnosed more than three years after acquiring HIV.

For the second target (90% of diagnosed people to be taking treatment), only 65% of people diagnosed with HIV are on antiretroviral treatment. Approximately one million people living with HIV are not receiving treatment. A major gap has opened between eastern and western Europe, with linkage to care after diagnosis being particularly slow in the east.

For the third target (90% of people on treatment to have an undetectable viral load), although 86% of people on treatment across the region are virally suppressed, due to the treatment gap, 1.2 million people are still living with unsuppressed HIV.

There are major disparities for key populations. Although 90% of people who inject drugs and living with HIV are diagnosed, only 50% are on treatment and only 39% are virally suppressed.

Anastasia Pharris of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) said that Europe would not meet the targets unless it addresses the prevention gap (including harm reduction, PrEP and condoms), the testing gap and the treatment gap.