Antiretroviral therapy has completely transformed HIV into an easily manageable condition for many people. However, if you are living with HIV, you need to take your medication as prescribed in order to fully control the virus and prevent it from damaging your health. Unlike older drugs that needed to be taken at exactly the same time each day, newer medications are more ‘forgiving’. While you should aim to take them every day, for most you do not need to worry about being a bit late.

Most HIV drugs follow specific pathways of absorption (the way the body absorbs the drug) and elimination (the way the body removes the drug). Pills are usually absorbed in the small intestine and elimination could happen via the liver and/or the kidneys. The health of these organs as well as our genetic make-up can lead to some variation in the rates of absorption and elimination. Nonetheless, the standard dosages that are recommended should overcome individual variation in the effective amount of drug present in the body. Additionally, some medicines, herbal and alternative treatments, and recreational drugs can have a more pronounced effect on the absorption and elimination of the HIV drugs. Sometimes they can lead to dangerously high or ineffectively low levels of the drug.

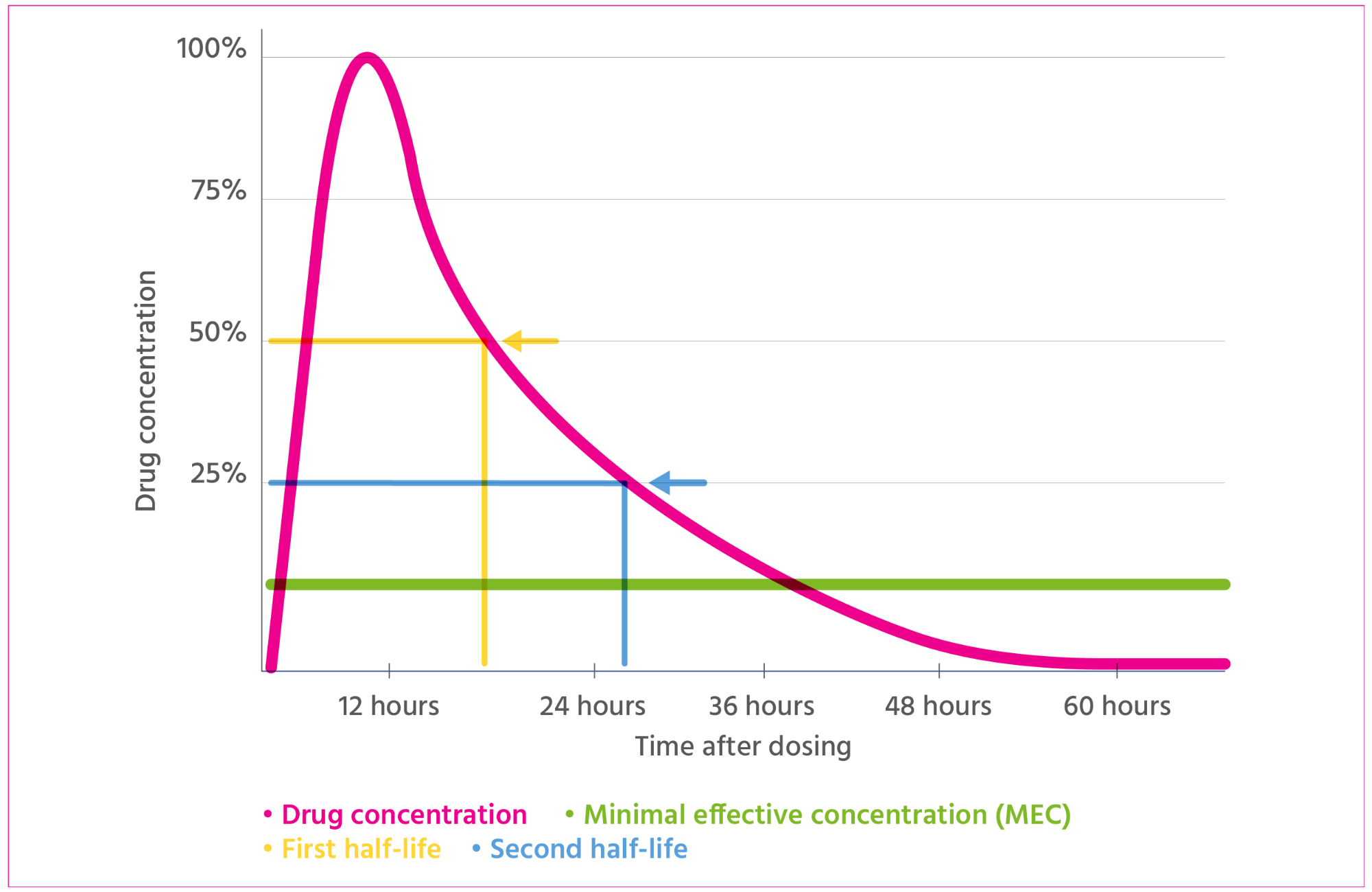

Different drugs have varying times and rates of absorption and elimination, and these two variables determine how long the drug stays in the body. Half-life is the unit used to describe how long a substance stays in the system. If a drug has a half-life of five hours for example, it will require five hours for your body to reduce its concentration by half. Most drugs require five half-lives for complete elimination, so our example drug will take 25 hours before it’s fully eliminated.

Although related to the half-life, another essential aspect of HIV drugs is how long they maintain effective concentrations in the system. Each drug has to reach a specific minimal effective concentration (MEC) in the body at which it is fully protective against the virus and minimises the risk of resistance. In other words, even if a drug has a very long half-life, it may still reach levels below MEC relatively quickly and no longer be effective. All HIV drugs are designed to maintain levels much higher than MEC until your next dose – the time it takes the drug to fall below MEC is longer than the recommended time between doses.

HIV drugs are also characterised by a barrier to resistance. This term is used to explain how quickly the virus can become resistant to a given drug if doses are missed. Fortunately, many of the newer drugs have a higher barrier to resistance than older drugs. The resistance barrier of a drug depends on which step of the virus' lifecycle it blocks, its target (whether it binds to a very vital place on the virus or not) and its binding strength (how strongly the drug binds to its target). A drug with a high barrier to resistance will bind to a vital place on the virus without which the virus cannot multiply. It will also bind very strongly, so the virus cannot escape and if the virus tries to change that part (mutate) in order to escape, that will be detrimental for the virus.

All of the above characteristics of drugs can be put together to assess a drug’s ‘forgiveness’. Forgiveness is a concept that helps understand how strict you need to be about taking your medication on time. Taking a more forgiving drug minimises the chance of unwanted outcomes, such as ineffectively low drug levels, resistance and treatment failure. A drug that falls below MEC much later than its dosing time and has a high barrier to resistance will be more forgiving than a drug that falls below MEC around the next dosing time and has a low barrier to resistance. The newer HIV drugs are generally more forgiving than the older ones, so a single missed dose is rarely a cause of treatment failure – but repeatedly missed doses can significantly raise the risk.

One exception to the above conclusion are the long-acting injectable formulations. While, as drugs, they obey most characteristics described so far, their different mode of delivery (non-oral) and release in the body (slower) significantly change their dynamics. Their very long dosing intervals, ranging from weeks to months, make a single missed dose very concerning and risky.