Key points

- Cases of HIV cure are exceptional, though there are also some cases of long-term control of HIV without having to take treatment.

- Three people are confirmed to have been cured of HIV after stem cell transplants replaced all the cells of their immune systems. Another three similar cases have been reported but it is too early to say if HIV has been completely cleared in these cases.

- Several cases of HIV control after stopping treatment have been reported. In these people, HIV may still be present at extremely low levels but it is being controlled by elements of the immune system.

- There are also a few cases of exceptional HIV control in people who have never taken antiretroviral treatment.

This page provides information on people who have been cured of HIV or appear able to control the virus without treatment. These cases have all been reported by scientists in medical journals or at scientific conferences. Sometimes, people are described as having long-term viral control without antiretroviral therapy (ART) or being in ‘remission’. This reflects uncertainty about whether HIV levels might eventually rebound.

While these cases are unusual, a major focus of HIV cure research involves finding out how these people manage to control their HIV, and developing therapies to help more people do the same thing.

HIV cure or control after stem cell transplants

Several cases of HIV cure or long-term viral control have been reported in people who received stem cell transplants to treat life-threatening leukaemia or lymphoma. Stem cells are cells produced by bone marrow (a spongy tissue found in the centre of some bones) that can turn into new blood cells.

In all but one of the cases, people with HIV received stem cells from a person who had natural resistance to HIV infection due to the presence of the double CCR5-delta-32 mutation. People with this rare genetic mutation do not have CCR5 receptors on their immune system cells, so HIV is unable to gain entry to cells.

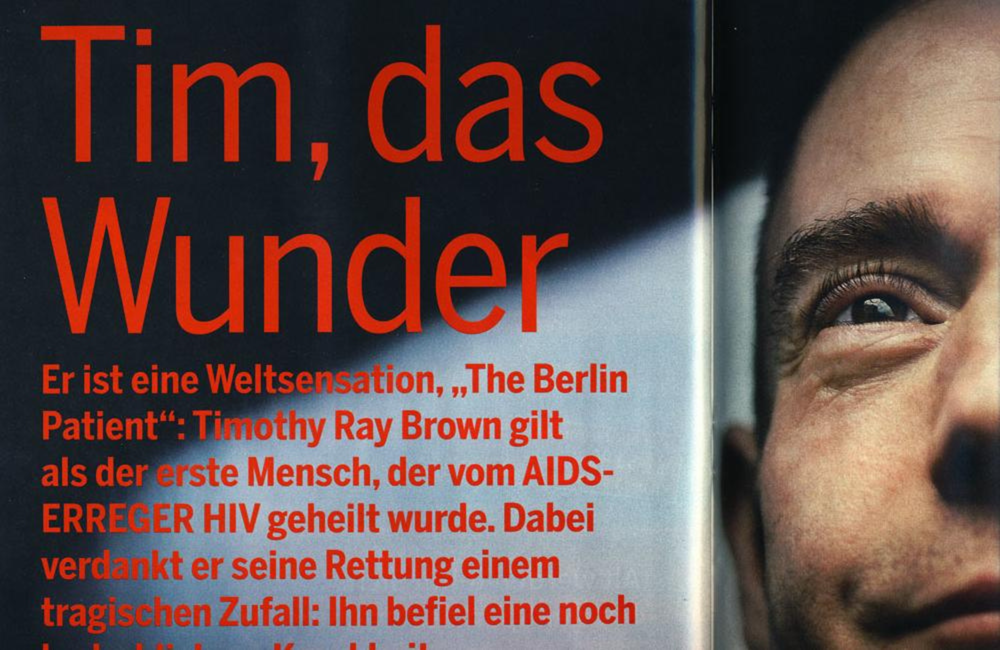

The first person cured of HIV was Timothy Ray Brown, an American then living in Berlin, who received two stem cell transplants to treat leukaemia in 2006. The donor had double copies of a rare gene mutation known as CCR5-delta-32 that results in missing CCR5 co-receptors on T cells, the gateway most types of HIV use to infect cells. He underwent intensive conditioning chemotherapy and whole-body radiotherapy to kill off his cancerous immune cells, allowing the donor stem cells to rebuild a new HIV-resistant immune system.

Brown stopped ART at the time of his first transplant but his viral load did not rebound. Researchers extensively tested his blood, gut, brain and other tissues, finding no evidence of replication-competent HIV anywhere in his body. In December 2010, Brown, known as the ‘Berlin patient’, began speaking to the press and at this point researchers started using the word ‘cure’ for him. It was revealed that Brown’s cure for HIV had been far from easy. Despite this, Brown survived for 14 years from the date of his bone marrow transplant without any sign of HIV returning. He moved back to the US and became an ambassador for HIV cure research. He died in September 2020 at the age of 54, of the leukaemia that first prompted his treatment.

Brown’s case led researchers to look for similar donors in subsequent situations where people with HIV needed stem cell transplants.

A second case was reported in 2019. Adam Castillejo, the ‘London patient’, received a stem cell transplant from a donor with natural resistance to infection as part of treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma. He stopped antiretroviral treatment 16 months after the transplant, by which time all his CD4 cells lacked CCR5 receptors. Still controlling the virus without ART a year later, Castillejo went public. The COVID pandemic prevented him and Timothy Ray Brown ever meeting, but they did talk on the phone before Brown’s death. He has now been off ART for five years with no trace of HIV.

Marc Franke, the ‘Düsseldorf patient’, received a stem cell transplant to treat leukaemia from a donor immune to HIV in 2013. More cautious than Castillejo, he did not stop taking ART until November 2018. His remission from HIV was first announced at the same time as Castillejo’s in 2019, although it attracted little attention at the time. In February 2023, after more than four years of extensive testing, his doctors declared him cured of HIV. Later that year, Franke told POZ magazine that he has met his donor and also keeps in contact with other people cured of HIV.

The ‘New York patient’ was described in February 2022. She was notable as being the first female case, and as of that date had been 14 months off ART without her HIV returning. She received a haplo-cord blood transplant to treat leukaemia in 2017. This is a different kind of stem cell transplant, used in circumstances where it is difficult to find a close genetic match, using cells from more than one donor. In this case, umbilical cord blood from a donor with the double CCR5-delta-32 mutation were supplemented by cells from a relative without the CCR5-delta-32 mutation. This procedure was necessary because the woman was mixed-race and the mutation that confers immunity to HIV is found almost solely in people of White European ancestry.

Paul Edmonds, the ‘City of Hope patient’, is a Californian named after the cancer centre where he was treated. As reported in July 2022, he received a stem cell transplant to treat leukaemia from a donor with a double CCR5-delta-32 mutation. He is the oldest person so far to experience viral control without treatment (63 years), has been living with HIV the longest (31 years), and has the lowest CD4 nadir (below 100). He stopped ART two years after his transplant and has shown no trace of HIV in the 17 months since, with his leukaemia also in remission. Edmonds went public to the newspaper USA Today in April 2023.

Most recently, Romuald, a French-Swiss man initially known as the ‘Geneva patient’ became the first person to experience HIV remission after a stem cell transplant in 2018 containing cells that did not have the double CCR5-delta-32 mutation. Based on the results of some previous transplants, scientists had assumed that HIV remission after a stem cell transplant was possible only after a transplant from a donor with the double CCR5-delta-32 mutation.

Romuald was diagnosed with HIV in 1990 at the age of 18 and had been taking antiretroviral treatment which fully suppressed HIV since 2005. He received the transplant after chemotherapy and radiotherapy to treat leukaemia. Host CD4 cells were completely replaced within a month of the transplant, but he had graft-versus-host disease, which occurs when donor immune cells attack the recipient’s body. This required treatment with ruxolitinib, a JAK 1/2 inhibitor, which has also been shown to reduce the size of the HIV reservoir. Ultrasensitive viral load testing could not detect HIV after the transplant and the man undertook a planned treatment interruption. No viral rebound had occurred 54 months after transplantation and HIV DNA levels continued to decline off treatment.

Speaking to French-language media in November 2023, Romuald explained that the treatment for his leukaemia was much more difficult than his treatment for HIV. “Isolation unit, heavy treatments, chemotherapy, radiotherapy,” he said. “It was the most difficult period of my life.”

He knew that stopping his HIV treatment would be risky, but chose to do so – both for himself and to advance scientific research. His intriguing case raises new questions about potential mechanisms that could lead to HIV remission.

Researchers stress that these are unusual cases and attempts to replicate them in other people undergoing cancer treatment have failed in some cases. Stem cell transplants are far too risky for people who do not need them to treat life-threatening cancer, and the intensive and costly procedure is far from feasible for the vast majority of people living with HIV worldwide.

HIV control after stopping treatment

Several cases of HIV control after discontinuing treatment have been reported. These individuals are known as post-treatment controllers.

In many but not all of these cases, the post-treatment controllers had received very early antiretroviral treatment – within the first few weeks after infection – which sometimes allows the immune system to ‘get ahead’ of HIV’s ability to evade the body’s natural response to it, producing broadly neutralising antibodies and other immune responses that stop more HIV being produced. This results in a much smaller than usual reservoir of cells containing intact proviral DNA. This strategy usually only works if people are treated very early, and it only produces long-term viral control in a fraction, such as a number of patients in France, the US and Germany.

In 2022, the latest report on the French ‘VISCONTI’ cohort identified six men and four women who started a course of ART within three months of infection, subsequently stopped it, have remained undetectable and have not re-started treatment. Viral loads before treatment were generally high and ART was taken for at least one year. Seven of the ten have now remained undetectable for more than ten years, including one man who stopped treatment 17 years ago.

However, there were an additional nine people in the cohort who had periods of low but detectable viral load during follow-up, and a further three people who needed to re-start ART due to raised viral loads.

It’s possible that cases of post-treatment control are not more commonly identified simply because, once having started ART, few people stop. A review of several studies suggests that around one person in nine treated very soon after infection may be able to control HIV for at least a year without treatment, while another suggested the proportion might be less than one in 20.

Children started early on ART are thought to be especially good candidates for post-treatment control as they can be started on ART very soon after infection, and they have fewer effector-memory T-cells, which are the type that become latent and hide HIV.

A South African child’s case was first presented in 2017. Born with HIV, he was started on ART when he was two months old and taken off it, as part of a clinical trial of early-treated children, when he was one year old. He was still undetectable off ART in 2022 at the age of 13. He had a very weak immune response to HIV but strong activity in a gene that codes for PD-1, an ‘immune checkpoint’ cell-surface protein that forces immune cells into latency – in other words, to force HIV to hide inside the reservoir cells and not come out.

A study of 281 mother-infant pairs identified five South African boys who had controlled HIV despite non-adherence to postnatal antiretroviral treatment. All infants in the study who had acquired HIV received antiretroviral treatment after delivery and 92% were also exposed to the medication in the womb. Infants had been off antiretroviral treatment for between three and 19 months at the time the study reported its findings. HIV control off treatment was associated with HIV that remained sensitive to type 1 interferon and virus with higher replicative capacity. The study suggests that there may be a gender difference in HIV control in infants, as girls are less likely to have HIV sensitive to type 1 interferon because they produce higher levels of type 1 interferon during gestation.

Another case of HIV control after discontinuing treatment in a child treated soon after birth was reported in 2020. A child in Texas started treatment within two days of birth, had a positive HIV DNA test two weeks after birth and discontinued treatment at the age of 13 months. Three years later the child had undetectable HIV RNA and HIV DNA was detectable at extremely low levels intermittently during the follow-up period.

However, there have been a number of reported cases in which HIV DNA was not detectable on any tests, but HIV subsequently rebounded. In 2013, details of a ‘Mississippi baby’ who received antiretroviral treatment from very soon after birth were reported. Treatment stopped after 18 months as the mother and baby stopped attending the clinic. HIV DNA was undetectable five months later when the mother and baby returned to the clinic and HIV remained undetectable for 27 months before viral load rebound occurred.

One remarkable case of post-treatment control is an Argentinian woman described as the ‘Buenos Aires patient’. She had not received treatment in early infection and there was nothing particularly advantageous in her medical history such as a consistently low viral load. On the contrary, when diagnosed in 1996, she had a low CD4 count (160) and at least one AIDS-related illness (toxoplasmosis). Her viral load, initially 2200, rose to 36,000 a year later due to adherence difficulties but after switching her ART regimen she never had a detectable viral load again – despite stopping ART in 2007 due to side effects.

When her case was reported in 2021, she had been off ART with an undetectable viral load for at least 12 years. Investigations in 2015 and 2017 could not find any replication-competent HIV DNA in 2.5 billion white blood cells and an upper limit of one unit of intact viral DNA in 390 million CD4 cells. Though her CD4 cells retained immune responses to HIV, her CD8 cells had very weak responses. Unusually, even for HIV controllers, she is now HIV negative, having lost her antibodies to the virus.

This woman does have HLA B*57, a genetic variant associated with lower viral loads and slow progression, but it does not seem to have stopped her developing a severe HIV infection in the first place. Exactly how she has managed to control her HIV so profoundly remains a mystery but her ‘seroreversion’ – disappearance of antibodies – and her sluggish CD8 response do seem to be extreme examples of processes seen in some other post-treatment controllers.

A Barcelona woman has controlled HIV for more than 15 years without treatment. Diagnosed with HIV during acute infection, she received four different immune-modulating drugs in addition to her normal antiretroviral treatment as part of a clinical trial. However, she was the only person out of 20 participants in the trial to maintain long-term viral control off ART, so it is difficult to know whether to ascribe her control to the extra treatment or not.

Like the Buenos Aires patient, she had had typical or even severe initial HIV infection. Her CD4 T-cells were receptive to HIV and her viral DNA turned out to produce replication-competent virus. But the CD8 T-cells of her cellular immune system and the natural-killer (NK) cells of her innate immune system both proved to have particularly strong activity against HIV. Even if her control was achieved only with extra therapy, the immune signatures of these controllers are interesting because they point the way towards how viral control might be induced in other people.

The reasons for viral control off treatment are still not fully understood. Learning how to reproduce this state in a much larger proportion of people, and in those who didn’t start treatment soon after infection, is a major goal of cure research.

HIV control without antiretroviral treatment

Few people with HIV can control viraemia without HIV medication. People that can maintain viral loads between 50-2000 copies without treatment are known as viraemic controllers. In the US and UK, less than 4% of people with HIV are considered viraemic controllers. Surprisingly, a recent study identified that 13% of people in the South African and Zambian PopART cohort were viraemic controllers. This is higher than in the US and UK studies, and most of the viraemic controllers identified in the PopART cohort were women. Some studies suggest that women might be more likely to control HIV without medication compared to other groups, but these studies are limited and require further investigation. Understanding how sex differences, and other factors, may contribute to viraemic control has the potential to inform cure strategies.

While viraemic controllers maintain low but detectable levels of HIV, some people can control virus to below 50 copies. ‘Elite controllers’ control HIV to undetectable levels in the blood, but viral material is still present elsewhere in the body. On the other hand, ‘exceptional elite controllers’ maintain undetectable viral loads because their immune system seems to have eliminated all intact viral material from their bodies.

Loreen Willenberg is a Californian woman considered to be an exceptional elite controller. She was diagnosed with HIV in 1992 at the age of 37. From the start she maintained a high CD4 count and undetectable viral load since diagnosis (except for one viral blip). She volunteered for studies of long-term non-progressors (people who maintain intact immune systems without treatment) and in 2011 learned that scientists could find no replication-competent HIV in her immune cells. Loreen went public about her story in 2019 and was featured in The New York Times in 2020.

It appears that Willenberg’s immune response to HIV is characterised by CD8 cells that have a strong and specific response to the parts of HIV that are most ‘conserved’. This means that they are the parts that change least, because to do so would impair viral fitness. They are therefore less likely to mutate away from the attention of the immune system.

In ‘elite controllers’ this highly selective immune attack has led to the only replication-competent DNA they have being located in so-called ‘gene deserts’ – parts of the host DNA that lack the necessary conformation to allow viral genes to activate. In Willenberg’s case, and in a few others, this process has gone further. Although some of her immune cells do contain ‘junk’ HIV DNA – proof that she once did have an active HIV infection – no replication-competent DNA can be found.

The scientists who investigated Loreen’s response to HIV and some other researchers, notably in Spain, have found a few other patients who appear to have achieved ‘self cures’. No more than nine of these ‘exceptional elite controllers’ have yet been documented.

‘The Esperanza patient’ is another example of an exceptional elite controller. This woman is named after her home town in Argentina. Diagnosed at the age of 21 in 2013, she took one six-month course of ART during pregnancy in 2020 to safeguard her baby but has never otherwise been on ART and has never had a detectable viral load test in nine years. As with Loreen Willenberg, researchers could find no replication-competent HIV DNA in 1.2 billion white blood cells, and also in 500 million placental cells sampled when she gave birth. In the case of this patient, doctors know that the likely source partner had a high HIV viral load, so her apparent self-cure is not due to viral factors.

There is also the case of an Australian man who appears to have cleared his own infection. This case was published in 2019 but attracted little attention, partly because the subject had an unusual combination of factors (a defective virus, one of his two CCR5 co-receptor genes missing and a response to HIV characteristic of slow progressors) that most people with HIV would not share. However, these factors did appear to have given his body more time than usual to mount a strong CD8 response, and a very specific CD4 response, to HIV. This is the kind of immune response researchers would like to replicate in other people.