Two studies of switching from oral to injectable PrEP in upper middle-income countries have found that the price of injectable long-acting cabotegravir (CAB-LA) would have to drop to considerably less than $100 a year for it to be cost-effective, compared to using oral tenofovir/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) pills. The studies were presented at the 12th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2023) in Brisbane, Australia.

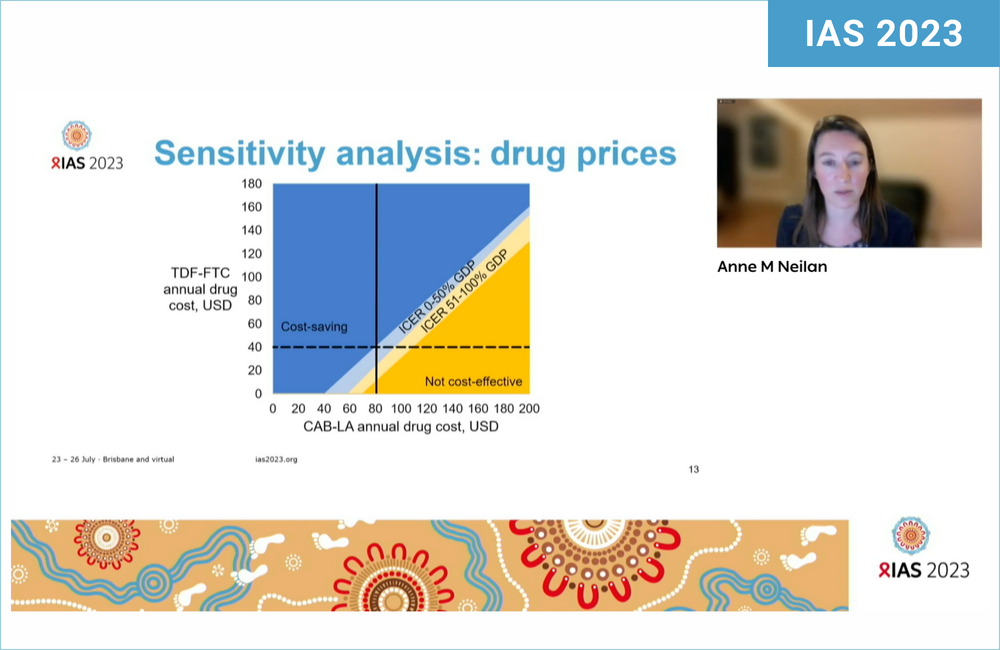

A study modelling CAB-LA’s introduction amongst adolescent girls and young women aged 15 to 30 in South Africa found that although it might halve the number of HIV infections compared to TDF/FTC, it would only be cost-effective if the medication cost less than $91 a year, and cost-saving if it cost just under $80 a year.

This is when comparing it to $40 a year for TDF/FTC, the price already paid in South Africa – and contrasts with the $250 a year it is forecast to cost when the generic companies licensed by CAB-LA’s makers, ViiV, start supplying it to 90 lower-income countries. Prices in the UK and US are closer to $10,000 and $20,000 respectively.

A Brazilian analysis found that unless CAB-LA sells for the same price or very little more than TDF/FTC, a higher number of infections would actually be prevented by sticking to oral PrEP. That is because Brazil could afford to distribute oral PrEP to so many more people, especially if it was taken on an event-driven rather than daily basis.

The different conclusions partly reflect the countries’ different epidemics. South Africa needs effective prevention for adolescent girls and young women, the group in which the HPTN 084 study showed that PrEP injections prevented 90% more infections than the pills.

In Brazil, however – which is, in any case, not one of the 90 countries targeted for generically produced CAB-LA – the HIV epidemic is concentrated in gay and bisexual men and transgender women. In the HPTN 083 study in this population, CAB-LA prevented 69% more HIV infections than TDF/FTC. But as oral PrEP has been highly effective in gay and bisexual men, injectables would not make such a big difference to HIV infection rates.

Injectable PrEP’s cost-effectiveness in young South African women

Presenting the South African study, Dr Anne Neilan of Harvard Medical School said that the need for an effective form of PrEP was urgent among young women in South Africa. Although in sub-Saharan Africa as a region, HIV infections have in the last decade decreased by 39%, the annual incidence of HIV among different groups of young women in South Africa still ranges from 3% to 7%.

“Preventing HIV in youth can avoid a lifetime of health care and associated costs”, she said. “But how much would we be willing to pay for CAB-LA’s improved efficacy?”

Her model simulated the outcomes among 10,000 women enrolling in FastPrEP – a locally delivered PrEP project run by the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation. The time horizon was set as ten years – in other words, infection rates are set as the number that would happen in 10,000 people over a decade.

Input assumptions of the model included:

- A mean age of 26

- Annual incidence with no PrEP of 3.2%; with TDF/FTC 1.9% (31% effective) and with CAB-LA 0.2% (89.5% more effective than TDF/FTC, or 94% overall).

- A retention rate of 88% after two years for TDF/FTC, or 85% on CAB-LA, taken from observed studies. Note retention means the number who stayed in the study, whether or not they actually took PrEP: adherence is included in the effectiveness estimates.

- Annual costs of $40 plus $12 clinic costs for TDF/FTC, or $80 plus $15 clinic costs for CAB-LA (the added clinic costs cover nurse training and follow-up for missed appointments). The total cost for 10,000 women would be $6.6 million for TDF/FTC or $7.1 million for CAB.

- Annual HIV care costs for people who acquired HIV ranged widely from $280 to $2690 a year, depending on their state of health and drug regimens.

There are two important omissions from the model. First, it does not try to model changes in HIV incidence and transmission rates over time, whereas under a successful PrEP programme, these should tend to fall. If they do, then PrEP becomes less cost-effective, because there are fewer infections to prevent. Another omission was the prevention of vertical (mother to child) transmission; if CAB-LA stopped significantly more babies becoming HIV positive, it would become more cost-effective.

South Africa does not have a formal cost-effectiveness threshold, but other studies have used a level of $3500 a year per life-year saved, which is 50% of the country’s per-capita GDP.

The outputs of the model – its predictions, if you like – were:

- Over ten years, there would be 1980 HIV infections among the 10,000 girls and women if they took TDF/FTC, but only 1080 if they took CAB-LA (45% fewer).

- Using CAB-LA would result in an increase of 150 life-years among the whole cohort averaged over ten years compared with using TDF/FTC. Note this is only an average increase from 8.58 to 8.595 life-years per person, or about 5.5 days, but this is a young cohort, the majority of whom would not acquire HIV anyway, or who might survive considerably beyond the decade if they did.

- If secondary HIV infections acquired by male partners of women who become HIV positive are also taken into account, the advantage of CAB-LA would increase by another 143 life-years.

The crucial figure in cost-effectiveness models is the ICER or incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. This is ‘bangs per buck’ – the cost, per life-year gained, of the new intervention compared with its alternative. This was $3440 a year, excluding secondary infections, if CAB-LA’s drug cost was $80 a year, which is just below the South African cost-effectiveness level. If secondary infections were included, it became cost-saving at just under $80 a year or cost-effective at $91 a year.

Dr Neilan concluded by saying that CAB-LA should be priced at no more than twice the price of TDF/FTC to be cost-effective in South Africa.

Affordability in Brazil

Dr Andrew Hill of Liverpool University presented a model based on the gay, bisexual and trans population of Brazil, a country with a faster-growing HIV epidemic than most countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Although 51,000 Brazilians, mainly gay men, are taking PrEP currently, the country needs many more to take it to make a serious dent in its HIV epidemic. Hill’s model supposed a target population of 250,000 gay men and trans women who were at highest risk of HIV – five times the current number receiving it. The model looked at how many could access PrEP under different cost scenarios, and how many infections this would prevent.

Brazil’s current PrEP budget is $6 million, and an important assumption in this model is that this is not going to change. However, Hill said that even if the prevention budget was varied substantially either way, it did not make much difference to the results.

Another important consideration is that Brazil is not one of the 90 countries included in ViiV’s licensing scheme for CAB-LA. Most of these countries are in Africa, with 22 in Asia and one in Europe (Ukraine). In Latin America there are four – Honduras, Nicaragua, Haiti and Bolivia. Andrew Hill questioned why three South American countries with GDPs lower than South Africa or Botswana – Ecuador, Colombia and Peru – were excluded from the scheme. Even Brazil has a lower GDP than Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Mauritius, which are all included.

The model’s inputs included:

- 5% annual incidence in the target population, without any PrEP

- An annual cost of $18 per person for HIV testing, monitoring and support

- 70% efficacy for TDF/FTC, with 33 people needing to take it to prevent one infection (an average from the PrEP randomised controlled studies)

- An additional 66% efficacy for CAB-LA, i.e. overall 89.8% efficacy.

The model then looked at how far $6 million would stretch to fund:

- Daily oral TDF/FTC PrEP at an estimated $48 a year

- Event-driven PrEP, assumed to have a quarter of the cost of daily PrEP, or $12 a year. This would cover just under two episodes a month

- CAB-LA costing $3500 a year: a price pitched between an estimate of the ViiV licence price and the UK price, which is typical for discounts Brazil has negotiated for other drugs

- CAB-LA at the ViiV licence price, estimated to be $250 a year

- CAB-LA at cost price, estimated as a minimum of $30 a year by the Clinton Health Access Initiative. This is not the price of manufacturing alone; it does include some profit and development costs.

These were all compared with no PrEP at all, as follows:

|

Scenario |

Number of PrEP users for $6m |

Annual HIV infections |

Annual HIV infections prevented |

|

No PrEP |

Zero |

12,500 |

None |

|

Daily TDF/FTC, $48 a year |

93,750 |

9219 |

3281 |

|

Event-driven TDF/FTC, $12/year |

230,769 |

4423 |

8077 |

|

CAB-LA, $3500 a year |

1707 |

12,423 |

77 |

|

CAB-LA, $250 a year |

22,727 |

11,480 |

1020 |

|

CAB-LA, $30 a year |

136,364 |

6177 |

6123 |

“When demand for PrEP is high and budgets are limited, the high price of CAB-LA could mean small numbers receive PrEP,” Hill said. “The result might be higher overall infection rates.”

He argued for the packs of PrEP pills and self-testing kits to be made more widely available – as condoms once were. “Until CAB-LA is affordable, mass distribution of event-driven TDF/FTC would prevent the most HIV infections,” he said.

He said that if some countries do want to provide injectable PrEP, compulsory licensing – where a country declares an emergency and starts manufacturing its own drugs – would be necessary. Brazil has in the past issued compulsory licences for the HIV drugs efavirenz and lopinavir/ritonavir as well as some cancer drugs.

He pointed out that the HPTN 083 and 084 studies came out about the same time as the COVID vaccine results. The vaccines have saved millions of lives, while injectable PrEP is still used by few people and has made almost no difference to public health. Injectable PrEP must become a lot cheaper if it is to fulfil its promise.

Neilan AM et al. Long-acting HIV (PrEP) among adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) in South Africa: cost-effective at what cost? 12th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2023), Brisbane, Australia, abstract OAE0302, 2023.

View the abstract on the conference website.

Hill A et al. Predicted HIV acquisition rates for cabotegravir versus TDF/FTC as PrEP in Brazil: effects of compulsory licensing. 12th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2023), Brisbane, Australia, abstract OAE0303, 2023.