More evidence that HIV integrase inhibitor treatment is associated with weight gain, and that people gain more weight after beginning treatment with an integrase inhibitor than people taking other drug classes, was presented this week at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2019) in Seattle.

Weight gain on integrase inhibitor treatment was first flagged up in late 2018 and, since the first reports, other research groups have been looking at weight gain in a wider range of patient groups.

The form of weight gain seen in people starting integrase inhibitor treatment is not the same as the fat redistribution syndrome, or lipodystrophy, observed when the first generation of protease inhibitors was used in combination with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) or when non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) were used in combination with older NRTIs, especially stavudine (d4T).

Whereas lipodystrophy involved accumulation of central abdominal or visceral fat, and loss of subcutaneous fat, weight gain on modern antiretroviral treatment consists of general fat gain – both subcutaneous and central fat – with an increase in waist circumference.

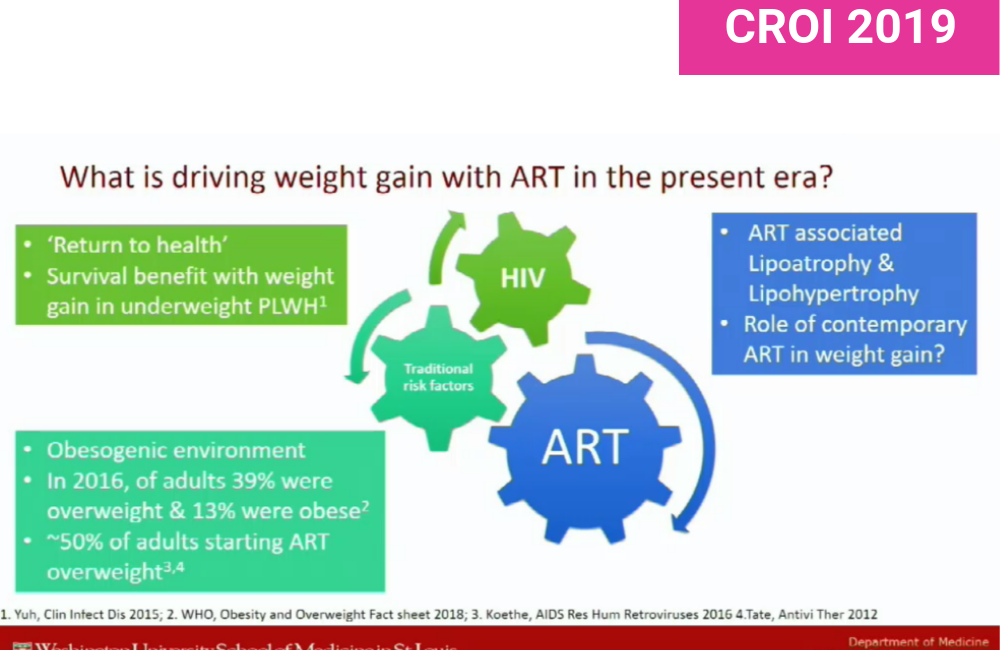

Weight gain after starting antiretroviral treatment is a common event; gaining a modest amount of weight is normal, especially in people with more advanced HIV disease or low body mass prior to treatment. It’s been dubbed 'return to health' weight gain.

However, what has been seen with some drug regimens – not just integrase inhibitors, but some protease inhibitors too – is more substantial weight gain. Some clinicians have raised concerns that weight gain might eventually increase cardiovascular disease risks, blood pressure and type 2 diabetes in populations which already have a high prevalence of obesity and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The VACS study showed that gaining five pounds (2.26kg) after starting treatment increased the risk of diabetes by 14%, while the D:A:D cohort found that every unit of body mass increase after starting antiretroviral treatment raised the risk of diabetes by 13%.

But is this weight gain caused by antiretroviral drugs or is it a product of environments that encourage people to eat unhealthily and be physically inactive? Moderating a discussion on weight gain after starting treatment, Jane O’Halloran of Washington University, St Louis, pointed out that up to half of adults starting antiretroviral therapy in the United States may already be obese. Weight gain after starting treatment may be occurring in adults who already have diets and lifestyles that predispose them to further weight gain.

On the other hand, asked Carl Fichtenbaum of University of Cincinatti, what if weight gain on regimens other than integrase inhibitors is being blunted by effects of certain drugs on fat deposits?

Studies presented at CROI this week attempted to shed more light on the problem, specifically: whether integrase inhibitors cause more weight gain than other drugs; how much weight is being gained and over what period; who might be at greater risk; and whether there is any difference between integrase inhibitors.

Are integrase inhibitors associated with greater weight gain than other drugs?

The largest study to report on this question, the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration, found that among people starting treatment for the first time, treatment with dolutegravir or raltegravir was associated with greater weight gain than treatment with NNRTI-based treatment. The cohort analysis looked at 24,001 people who started treatment between 2007 and 2015. During that period, 4740 people started treatment with an integrase inhibitor (1681 raltegravir, 2124 elvitegravir and 935 dolutegravir).

After five years on treatment, people taking an integrase inhibitor had gained a median of 6kg, compared to 4.3kg for people who started an NNRTI (p < 0.001). There was no difference in weight gain between people who started an integrase inhibitor or a protease inhibitor. (Bourgi)

The Women’s Interagency Health Study examined its cohort of 1118 women who had undetectable viral loads between 2008 and 2017 on treatment, 234 of whom switched to an integrase inhibitor during that period. This cohort had a high prevalence of obesity and a mean body mass index of just over 30 at baseline. There was no significant difference in body weight by demographics or by drug regimen at baseline, with mean weight of approximately 80kg. Women who switched to an integrase inhibitor gained 2.14kg more than women who did not switch. (Kerchberger)

Dallas Parkland Hospital looked at 4048 patients who started treatment between 2009 and 2017, with median exposure to antiretroviral treatment of 6.7 years. They looked at differences in changes in body mass index after starting treatment between people who started regimens based on an NNRTI, a protease inhibitor or an integrase inhibitor.

The median increase in body mass index was greatest in the integrase inhibitor group (+0.32/m2 per year) and smallest in the NNRTI group (+0.22/mm2 per year). (Bedimo)

In summary, most studies did find an association between integrase inhibitor treatment and weight gain, in previously untreated people and in people switching from another regimen.

One study did not find an association. An analysis of clinic databases in 21 US states, covering 3468 people with suppressed viral load for at least one year, looked at weight gain between 2013 and 2018. They found that patients gained an average of 3% a year in weight, but in a discussion on weight gain research Grace McComsey pointed out that most people are not gaining substantial weight – “only 30% gained more than 3%”.

Regression analysis failed to show an association between integrase inhibitor treatment and weight gain. Instead, significant predictors of weight gain in this population were low body mass index at baseline, being overweight at baseline, hypogonadism (low testosterone), protease inhibitor treatment, and psychiatric disorder. (McComsey)

The HIV prevention study HPTN 077 looked at weight gain in 199 HIV-negative people who received oral induction treatment and subsequent injectable cabotegravir. Weight was measured at each study visit to week 41 and no difference in weight gain was seen between those who received cabotegravir or placebo – both groups gained around 1kg. The investigators commented that an interaction between HIV infection and integrase inhibitor treatment may be an important contributor to weight gain on antiretroviral treatment. (Landovitz)

Are some people at greater risk of weight gain on integrase inhibitor treatment?

A review of 972 people who switched to an integrase inhibitor in AIDS Clinical Trials Group studies found that in the two years after switching, white or black race, age 60 or over, or a pre-switching body mass index of 30 or above (obese) were associated with greater weight gain in women. In men, only age over 60 was associated with weight gain. Dolutegravir was associated with the greatest weight gain and the gains in weight after starting treatment were larger than those expected for a person’s age. (Lake)

A review of 437 patients in the HIV Outpatients Study found that among patients who switched to integrase inhibitor-based treatment after viral suppression on another regimen, weight gain was significantly greater in non-Hispanic black patients and in people with no prior history of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor use. (Palella)

Are there differences between integrase inhibitors in weight gain?

In the NACCORD study, researchers looked at weight gain after two years on each integrase inhibitor and compared this with weight gained by people starting treatment with an NNRTI or a protease inhibitor. Taking into account that fewer people received dolutegravir because it was licensed after raltegravir and elvitegravir, the investigators found that patients on raltegravir or dolutegravir gained significantly more weight than people taking NNRTI treatment, while people taking elvitegravir gained less weight than people taking a protease inhibitor.

In the Parkland study discussed in a previous section, women gained more weight than men on dolutegravir and raltegravir, but not on elvitegravir. Black people gained more than other ethnic groups on dolutegravir, but not on other integrase inhibitors. In the entire cohort, people taking elvitegravir gained more weight than people taking dolutegravir or raltegravir. (Bedimo)

In summary, no clear pattern emerged from the research presented at CROI regarding the effects of various integrase inhibitors.

Bedimo R et al. Differential BMI changes following PI- and InSTI-based ART initiation by sex and race. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, abstract 675, 2019.

View the abstract on the conference website.

Bourgi K et al. Greater weight gain among treatment-naïve persons starting integrase inhibitors. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, abstract 670, 2019.

View the abstract on the conference website.

Watch the webcast of this session on the conference website.

Kerchberger AM et al. Integrase strand transfer inhibitors are associated with weight gain in women. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, abstract 672, 2019.

View the abstract on the conference website.

Watch the webcast of this session on the conference website.

Lake J et al. Risk factors for weight gain following switch to integrase inhibitor-based ART. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, abstract 669, 2019.

View the abstract on the conference website.

Watch the webcast of this session on the conference website.

Landovitz RJ et al. Cabotegravir is not associated with weight gain in HIV-negative individuals: HPTN 077. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, abstract 34LB.

View the abstract on the conference website.

Watch the webcast of this session on the conference website.

McComsey GA et al. Weight gain during treatment among 3.468 treatment-experienced adults with HIV. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, abstract 671, 2019.

View the abstract on the conference website.

Watch the webcast of this session on the conference website.

Palella FJ et al. Weight gain among virally suppressed persons who switch to InSTI-based ART. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, abstract 674, 2019.