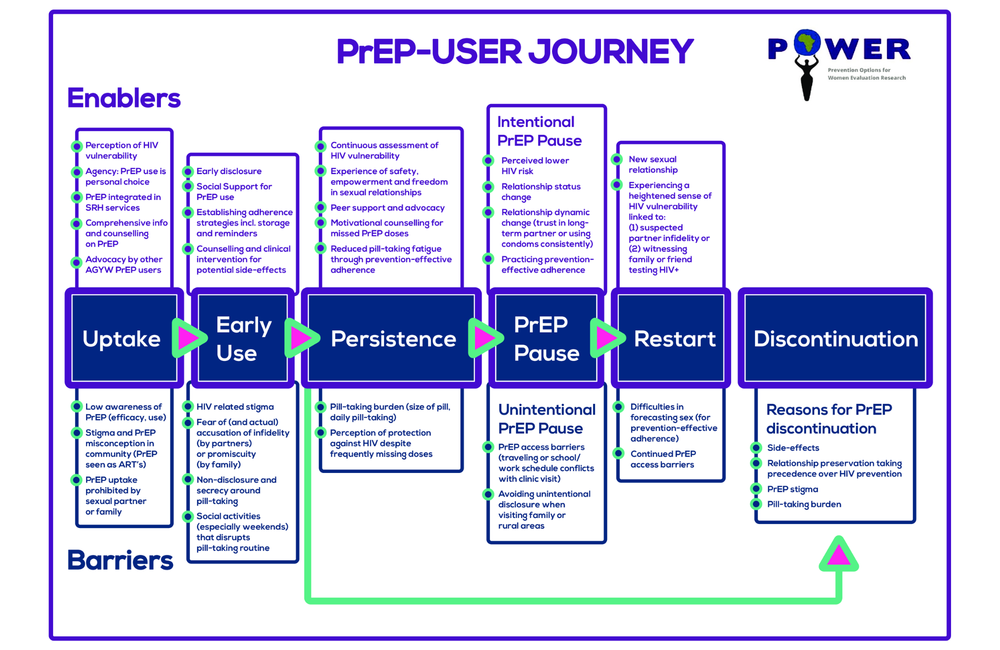

A qualitative study in South Africa and Kenya looked at barriers and facilitators along the PrEP journey of adolescent girls and young women. Intentional PrEP pauses and restarts, corresponding to changing circumstances and seasons of risk, were common among participants in this study.

The researchers suggest that PrEP providers should be encouraged to accept seasons of risk and normalise PrEP pauses and restarts among adolescent girls and young women.

Globally, over 1,000 adolescent girls and young women aged 15-24 acquire HIV every day. Safer sex can be difficult to negotiate for adolescent girls and young women due to gender inequality and violence, power imbalances, difficulty negotiating condom use, and low perception of HIV vulnerability.

PrEP provides HIV prevention without the knowledge or consent of sex partners, increasing the autonomy of users. Yet multiple barriers remain to PrEP scale-up, including stigma, confusion between PrEP and antiretroviral therapy, low awareness, and lack of social support. This research examined barriers and facilitators to PrEP use among adolescent girls and young women.

Led by Elzette Rousseau of the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre at the University of Cape Town, researchers interviewed participants from the Prevention Options for Women Evaluation Research – POWER – study, an implementation science study to develop scalable PrEP delivery strategies for adolescent girls and young women in Africa.

Eligible participants were HIV-negative cisgender (not transgender) women and girls who had been sexually active at least once in the previous three months. Independent interviewers conducted 104 in-depth interviews and 33 focus groups that lasted between 45 minutes and two hours in local languages. Participants talked about experiences, thoughts, and decisions on PrEP through the lens of fictional personas.

A total of 137 participants aged 16 – 25 (average age 21) were interviewed in this study. Forty-six were from Johannesburg, 43 from Cape Town, and 48 from Kisumu, Kenya. Most (81%) were unmarried with a partner. Sixty per cent of participants didn’t know the HIV status of their partner(s), while 5% reported a partner living with HIV and 36% reported an HIV-negative partner. Almost half (49%) of participants lived with parents, followed by other family (25%) or their sex partner (17%). A little under half (47%) reported alcohol use. Over two-thirds (64%) had gonorrhoea and/or chlamydia at enrollment.

PrEP uptake

Among this cohort, baseline awareness of PrEP was low, with most participants learning about PrEP after being referred to the POWER study when seeking sexual health services. Participants were enthusiastic about PrEP, noting it provided a sense of safety and freedom and helped level the unequal gender power dynamic with partners.

Knowledge of vulnerability to HIV was a motivating factor for PrEP use. Participants reported being vulnerable to HIV due to relationship dynamics and/or sexual assaults:

“Well, every girl is at risk of HIV and every day because we live in a horrible world, where we are raped, we are exposed to a lot of bad stuff, so I felt PrEP was just the answer you know, just prevent a disease and not to worry so much about it.”

Participants who started PrEP on the day of study enrollment believed it was a personal decision and didn’t feel compelled to consult their family or sexual partners. Making that decision for themselves boosted self-esteem:

“It has made me feel proud about myself, because it was my decision to take PrEP…based on my own needs and not other people’s [needs]—I saw that PrEP [is] good for me.”

Knowing that peers took PrEP and seeing other PrEP users at the clinic helped normalise use and facilitated uptake. Stigma and misconceptions among families, peers, and community members were often underlying decisions to delay or decline PrEP.

Participants discussed confusion between taking PrEP for prevention and antiretrovirals (ART) for HIV, as well as perceptions that PrEP users are promiscuous, cheating on their partners, or sex workers. Some participants therefore sought approval from their family or partners before accepting PrEP:

“The thing is, after that incident [hearing about PrEP from the clinic] I went to my mother and told her. And she said if I know it will help me, I should take it. Then I decided to come get it [the following day].”

Lack of approval from their support system led to participants declining PrEP:

“He [boyfriend] asked me why I should use it. ‘Don’t you trust me?’ he asked. ‘Do you have a side partner?’ he continued. Those were the questions asked and I decided not to use it.”

Other concerns leading to PrEP delays or refusals included concerns around efficacy and side effects, pill-taking burden, and how long a person would be on PrEP. Some participants ultimately started PrEP after taking time to think about how it fits into their lives, and after learning more about it from the media or peers.

Early PrEP use (0-3 months)

Deciding whether or not to disclose PrEP use was a key feature of the early phase. When participants did disclose, it was most often to family or the people they lived with. Social support after disclosure helped with adherence and with integrating PrEP into their daily lives. In particular, approval from their mothers was significant to participants:

“It was supportive like at least there is someone who knows that I am taking them, I am not hiding this thing. Especially if my mother knows, then I am okay. About others and stuff, no, but just as long as my mother [knows].”

Participants were more hesitant to disclose PrEP to partners, fearing distrust, conflicts, or potential breakups:

“My thoughts were that he [sexual partner] might not understand me and might think that I am sick [have HIV]. So, I was ashamed to tell him.”

This fear led some participants to hide their use and adjust their pill-taking times based on when they saw their partner. Finding discreet storage was a practical concern during early PrEP use as participants integrated PrEP into their daily lives.

Establishing pill-taking habits was another feature of early PrEP use. Participants discussed using daily routines, alarms, or taking PrEP with other daily pills, such as contraception.

Occasionally missing PrEP doses was the norm among participants, with most being unintentional and related to unanticipated circumstances or disruptions in routine. Participants most often reported missing doses on the weekends, due to social activities, drinking, or staying at a sex partner’s place:

“Ja, it [missing pills] happened, I had gone to a party [laughs] so I came back very late…I was just drunk and I had brought my friends home. I did not think about it [taking PrEP] that day.”

Discontinuation

Over half (59%) of participants interrupted or stopped PrEP within the first three months of use. Perceived side effects and the size of the pill were reasons for stopping:

“I changed my mind because of the side effects… and the size [of PrEP pill]. My mother and aunt have their medications that they are taking but out of all these medications my PrEP pill was the biggest one… and I didn’t feel well even when I was taking it.”

The burden of daily pill use was another reason participants discontinued, as was the lack of physical cues that could remind someone to take a pill:

“Sometimes I just forget [to take PrEP], I don’t know why… maybe because there will be no pain that will remind me that actually, it’s paining now, go and drink these tablets and stuff.”

Others discontinued after experiencing stigma, disapproval, or lack of support:

“The people in my life had the influence that PrEP is not something good, a lot of people. Like my mother because she is also against PrEP. So, as they think that PrEP is not good, I stopped PrEP.”

Enacted stigma – or the fear of stigma – made establishing a PrEP routine challenging, leading to missed doses, discouragement, and for some, discontinuation:

“…cause every time I take them [PrEP pills], my roommate used to ask me, ‘why are you always taking pills’, she didn’t know anything about PrEP…And sometimes you will be embarrassed that maybe she would think that I am HIV positive or something.”

Preserving relationships was another factor influencing PrEP discontinuation. Through the fictional personas, participants shared that fear of violence or breakups may lead to stopping PrEP.

“…pressure probably from her partner. He might say, ‘if you are continuing [to take PrEP] sisi (sister), then I request that we break up then”.

PrEP persistence

Consistent PrEP use was empowering for participants. Participants discussed positive shifts in relationship dynamics, such as more agency and better communication, and positive impacts on sexual behaviour, such as more comfort during sex without condoms:

“I just feel PrEP is really helping, so I am not afraid [of HIV]…It has made me feel so comfortable [with my partner]”.

However, PrEP felt like a big responsibility. Participants needed to motivate themselves to take pills daily and anticipate changes in routines that would affect PrEP use. Those who persisted on PrEP described feeling empowered and protected owing to good adherence, while feeling guilt or stress when they missed doses.

Taking intentional breaks during periods of decreased HIV vulnerability helped lessen the pill-taking fatigue. So did reminding themselves that their current vulnerability to HIV – and PrEP use - wasn’t permanent.

Participants who didn’t persist on PrEP had contradictory beliefs: they vocalised the most doubts about PrEP’s efficacy, yet they reported feeling high levels of protection despite frequent missed doses. They seemed more impacted by rumours and misconceptions and suggested more peer advocacy to de-stigmatise PrEP use. They also expressed preference for smaller pills or injectable PrEP, which would eliminate or reduce barriers related to privacy, storage, and frequency of clinic visits.

PrEP pause and restart

Pausing PrEP for one to nine months was common among participants. Some pauses were intentional, due to lower perceived vulnerability to HIV, to avoid disclosure, or when PrEP use was difficult to fit into their lives, such as during travel.

Vulnerability to HIV (and perceived vulnerability) was dynamic, with participants pausing PrEP during breakups, time away from partners, when using condoms consistently, or when participants had more trust in their partners:

“You take it, after seven days that is when you can have sex with someone. This is because my partner is from [name of area] and whenever he is away, I can relax a bit [can pause PrEP use]. I will resume using it when he is coming back. He can tell me that he will come on such a day then it is up to me to plan myself for his coming.”

Many participants paused PrEP when travelling home to family, to avoid disclosure

“Sometimes maybe you visit [rural] home and then you don’t take them because you are afraid that there is a person who will see that you are taking the pills…you will find that they will spread the news wide, they will say you are sick [have AIDS], all that stuff. You will no longer be appealing.”

Focus group participants from South Africa discussed the December holiday season, a time of travelling and parties. Some participants preferred to stop PrEP during that time, while other participants suggested a revised pill taking schedule instead due to continued or increased vulnerability to HIV.

Unintentional PrEP pauses often stemmed from out-of-town travel, and clinic access barriers such as conflicting schedules or transportation.

“I was in the village and couldn’t access it. I came back, and it took two months and a half [that she was off PrEP/away in the village). I told my friend that we need to go back [to clinic] for the drugs, and that is how we came for refills.”

Many participants restarted PrEP upon restored access to PrEP services, or when reconciling with a sex partner or starting a new relationship. An increased sense of HIV vulnerability, such as if a friend or family member received an HIV diagnosis or due to the changing sexual behaviours of partners, also led to restarts:

“I paused [PrEP use] because my sexual partner agreed that we will be using condoms, but after sometimes, he refused [condom use] and I started again to use PrEP.”

Most participants didn’t discuss pauses or restarts with providers, instead relying on their own assessments and knowledge of prevention-effective adherence.

Conclusion

The PrEP journey of adolescent girls and young women is greatly impacted by social, relational, practical, and structural factors. In this study, PrEP use was dynamic, with intentional pauses corresponding to seasons of increased or decreased perceptions of HIV risk due to relationship changes, time away from partners, and travel.

Results from this study underscore the need for long-acting, discrete HIV prevention methods among adolescent girls and young women to reduce some of the barriers that daily pill-taking poses. Strategies to destigmatise PrEP use, address misconceptions, and utilise peer networks can all support PrEP scale-up.

PrEP providers should be encouraged to accept “seasons of risk” and normalise PrEP pauses and restarts among adolescent girls and young women, by counselling them on prevention effective adherence while affirming their choices and autonomy.

Rousseau E et al. Adolescent girls and young women’s PrEP-user journey during an implementation science study in South Africa and Kenya. PLOS One, 14 October 2021 (open access).

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258542

Full image credit: Enablers and barriers at key stages in young women’s PrEP user journey from PrEP uptake to early use and persistence or discontinuation, including periods of PrEP pauses and restarts. Graph from the journal article. Available at journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0258542 under a Creative Commons licence 4.0.