People taking abacavir as part of their antiretroviral regimen were 40% more likely to experience a heart attack, stroke or other serious cardiovascular event than people not taking the drug, and this risk was not affected by pre-existing cardiovascular problems, a large international study of people with HIV in Europe and Australia has found.

The study also found that the absolute risk of a cardiovascular event was low, but not negligible, at just under 5 cases per 1000 person-years of follow-up, or 1 case for every 200 people taking abacavir each year.

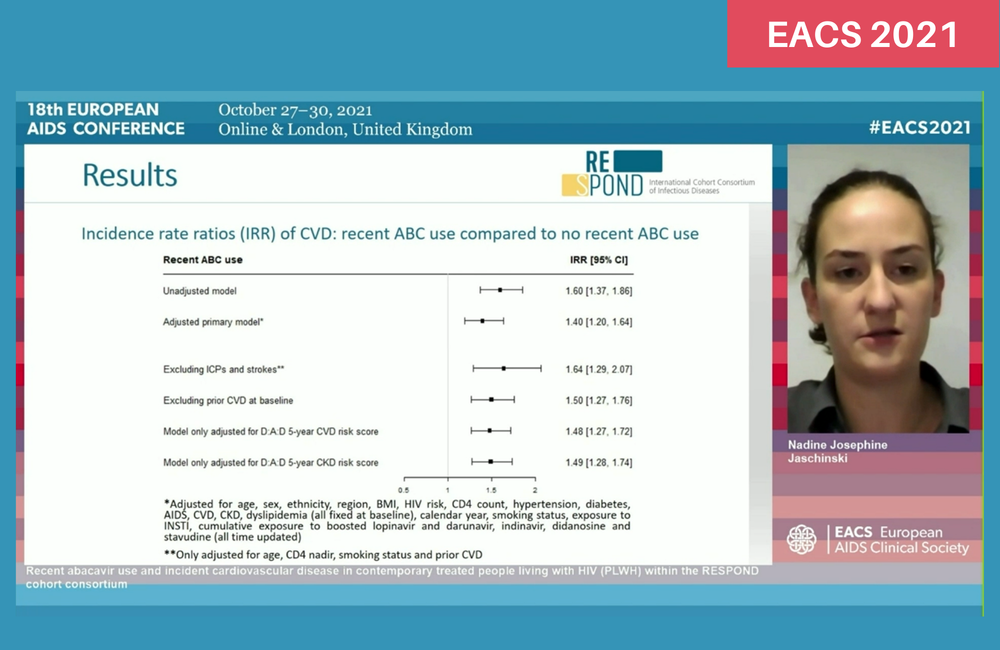

The study findings, presented at the 18th European AIDS Conference (EACS 2021) by Nadine Jaschinski of CHIP at the University of Copenhagen, confirm previous research showing a link between abacavir and a raised risk of cardiovascular problems. Abacavir may raise the risk by causing increased platelet reactivity, leading to increased blood clotting, thrombosis and blockages leading to heart attack or stroke.

Has guidance to avoid TDF in people at higher risk of chronic kidney disease channelled people with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease onto abacavir?"

Abacavir’s association with cardiovascular disease first came to light in 2008, in an analysis of the D:A:D observational cohort. Subsequent investigations have reached conflicting conclusions, but treatment guidelines have adopted a cautious approach. The British HIV Association and the European AIDS Clinical Society recommend that people at higher risk of cardiovascular disease should not take abacavir.

But these recommendations are largely based on studies carried out in the 2000s and may not reflect the risks present today, when people start treatment earlier after diagnosis. The characteristics of people with HIV on treatment, including their age, may have changed.

There are also questions about the impact of guidance on the risk associated with abacavir. Has the guidance to avoid abacavir in those at higher risk of cardiovascular events eliminated the risk? Or has guidance to avoid the older formulation of tenofovir (TDF) in people at higher risk of chronic kidney disease channelled people with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease onto abacavir?

People with chronic kidney disease are at higher risk of cardiovascular events, due partly to risk factors common to the two conditions, but also because of the high prevalence of raised blood pressure in people with chronic kidney disease, even at its earliest stages.

To answer these questions, Danish investigators looked at everyone in the RESPOND cohort, an international collaborative study of 17 cohorts of people with HIV in Europe and Australia. They assessed the risk of cardiovascular events in everyone included in the cohorts from January 2012 to December 2019.

The study population consisted of 29,340 people with HIV, 74% male, with a median age of 44 years. Thirty-four per cent took abacavir during the follow-up period, and of these participants, 32% were taking it with a boosted protease inhibitor.

Cardiovascular risk factors were common in the study population: 61% had raised lipids at baseline, 19% had raised blood pressure, 28% were smokers and 4% had diabetes.

Firstly, the investigators calculated the odds of starting abacavir during the study period according to risk of chronic kidney disease or cardiovascular disease. Compared to people at low risk of a cardiovascular event within five years (less than 1% risk), people at moderate risk (1-5% risk) were 20% less likely to start abacavir during the study period, and those at high risk (5-10% risk) or very high risk (>10% risk), 25% and 29% less likely to start abacavir respectively.

Compared to people with a low five-year risk of chronic kidney disease, people at moderate risk were 17% less likely to start abacavir and people at high risk were 12% more likely to start abacavir.

These findings suggest that although guidance on the avoidance of tenofovir in people at high risk of chronic kidney disease is not channelling people onto abacavir, people with a high risk of cardiovascular disease continue to be exposed to abacavir.

The investigators calculated the risk of a cardiovascular event in people who had taken abacavir within the past six months compared to people not exposed to the drug. During the study period, 748 cardiovascular events were recorded (299 heart attacks, 228 strokes and 221 invasive cardiovascular procedures) during a median follow-up of 4.4 years, an incidence rate of almost five cases per 1000 person-years of follow-up (IR 4.7 per 1000 PYFU, 95% CI 4.3-5).

The incidence of cardiovascular events was 40% higher in people taking abacavir or recently exposed to it after adjusting for demographic and cardiovascular risk factors (adjusted incidence rate ratio 1.40, 95% CI 1.20-1.64). This elevated risk persisted when the analysis was restricted to people without a previous history of cardiovascular disease or to heart attack cases alone.

Furthermore, there was no evidence that the risk of a cardiovascular event in people taking abacavir was affected either by predicted five-year cardiovascular risk or chronic kidney disease risk. In other words, people with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease were just as likely to experience an event as people at very high risk.

Jaschinski NJ et al. Recent abacavir use and incident cardiovascular disease in contemporary treated people living with HIV (PLWH) within the RESPOND cohort consortium. 18th European AIDS Conference, London, poster BPD1/3, 2021.