Children with HIV who had received antiretroviral treatment since early childhood had significantly higher insulin resistance and worse metabolic profiles than HIV-unexposed children from the same community and may be at greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, a study from South Africa reported at last week’s 11th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science has found.

Insulin resistance develops when cells in muscles and organs such as the liver don’t respond as well to insulin and don’t take up glucose from the blood efficiently. To compensate, the pancreas produces more insulin. Eventually, insulin production may fail to keep up with rising glucose levels. This leads to the development of a ‘pre-diabetes’ state and metabolic syndrome.

Insulin resistance can lead to the development of several serious health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure and stroke. Insulin resistance also raises the risk of some cancers, including bladder, breast, colon, cervix, pancreas, prostate and uterine cancers.

Both HIV and some antiretrovirals used in HIV treatment can cause insulin resistance. Insulin resistance also develops in people who are overweight. Weight gain often occurs after starting antiretroviral treatment. Some people, notably those taking tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) and an integrase inhibitor, may gain a substantial amount of weight and become overweight or obese.

However, large cohort studies in the United States and France show no increased risk of insulin resistance or diabetes in people taking integrase inhibitors. Women in Botswana who took the most widely used integrase inhibitor (dolutegravir) during pregnancy had a lower risk of developing gestational diabetes than women taking efavirenz.

Insulin resistance in children with HIV could lead to the development of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes in adolescence or early adulthood, raising the risk of cardiovascular disease. What’s unclear is the extent to which HIV or antiretrovirals raise the risk of insulin resistance and metabolic disorders in children.

To investigate these questions, Claire Davies at Stellenbosch University in Cape Town, South Africa, and colleagues in South Africa and the United States looked at children with HIV who had taken part in the two trials of early antiretroviral treatment for infants and young children (CHER and P1060).

Metabolic changes between 2014 and 2020 in 141 trial participants were compared to a control group of 169 HIV-exposed children without HIV (i.e. children of HIV-positive mothers), and 175 HIV-unexposed children without HIV (i.e. children of HIV-negative mothers). The control groups were recruited from the communities in which the trial took place.

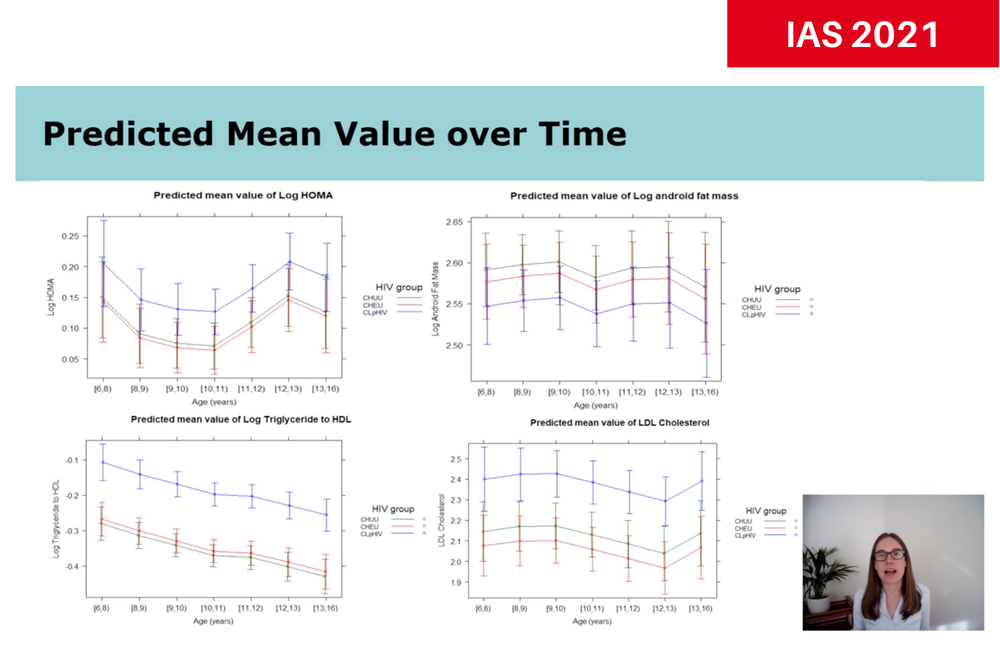

Children underwent metabolic and cardiovascular monitoring once a year. The researchers recorded insulin and blood glucose levels, blood pressure, triglyceride, HDL and LDL cholesterol levels, and measured fat mass using DEXA scans. Children contributed a median of three measurements to the analysis.

At baseline, children with HIV were significantly younger than children in the control groups (median 8.7 years compared to 9.4 and 9.2 years in the control groups, p<0.001) and slightly shorter in stature. HIV-unexposed children without HIV were less likely to be Black than other children in the study (P<0.001). Children with HIV were taking an antiretroviral regimen consisting of zidovudine, lamivudine and either lopinavir /ritonavir (83%) or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (20%).

The primary study outcome was the mean level of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). Multivariable analysis showed that the mean HOMA-IR was 14% higher in children with HIV compared to HIV-unexposed children without HIV (95% confidence interval 1.03-1.25, p<0.01). Insulin resistance and other metabolic measures did not differ significantly between HIV-negative children who were exposed or unexposed to HIV.

The mean triglyceride-to-HDL cholesterol ratio (a marker of increased cardiovascular risk; insulin resistance depresses levels of ‘good’ HDL cholesterol) was 49% higher in children with HIV compared to HIV-unexposed children without HIV (95% CI 1.36-1.63, p<0.0001).

Children with HIV had lower fat mass than HIV-unexposed children without HIV (-9%, 95% CI -18% to -0.01%).

When the evolution of mean metabolic values over time was projected, based on observed changes, insulin resistance rose until the age of 13 before falling slightly, but the ratio of triglycerides to HDL cholesterol continued to decline with age.

One limitation of the study is that owing to the average age of the study population and the amount of follow-up data, the study findings may not fully reflect changes during puberty and their effects on insulin sensitivity. Only 9% of participants had reached the final stage of puberty by their last study visit, she pointed out. Although adolescents may experience improvements in insulin sensitivity as they mature, she noted that pre-pubescent insulin resistance has been shown to predict adolescent insulin resistance in other studies.

Children and adolescents should be monitored carefully for subclinical cardiovascular disease and receive appropriate preventative interventions, she concluded.

Davies C et al. A longitudinal study on insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in children with perinatal HIV infection and HIV exposed uninfected children in South Africa. 11th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science, abstract OAB0503, 2021.