People with HIV on antiretroviral treatment showed evidence of broad immune responses against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, according to a pair of studies presented last week at the 11th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2021). The ability to develop natural immunity against the coronavirus bodes well for a good response to COVID-19 vaccines.

Compromised immunity is linked to poor COVID-19 outcomes, and studies to date have reached conflicting conclusions about whether people living with HIV are at greater risk for severe COVID-19 and death. At IAS 2021, an international analysis that mostly included people from South Africa found that HIV-positive people have an increased risk of hospitalisation and death from COVID-19. However, a large study from the United States did not see a greater risk, while a Spanish study found that having a detectable HIV viral load, lower CD4 count and co-morbidities were risk factors for severe COVID-19.

Dr Juan Tiraboschi of Bellvitge University Hospital in Spain and colleagues assessed immune responses in HIV-positive and HIV-negative people who had recovered from COVID-19. They looked at both humoral immunity, or antibody responses, and cellular immunity, or B-cell and T-cell responses. Both components of the immune system play an important role in fighting the coronavirus.

The analysis included eleven people with HIV. In this group, the median age was 52 years and all were on antiretroviral therapy (ART). Prior to COVID-19 diagnosis, their latest CD4 cell count ranged from 284 to 1000 cells/mm3 (seven had more than 600 cells/mm3) but five had had a nadir (lowest-ever) CD4 count below 220. Five had mild and six had moderate-to-severe COVID-19. The researchers also analysed 39 HIV-negative people, 20 with mild and 19 with moderate-to-severe COVID-19. Immune responses were measured at three and six months after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Almost all the HIV-negative people (94%) and 73% of the HIV-positive people had detectable SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies at three months. Everyone with severe COVID-19 – whether they had HIV or not – had antibodies, but 60% of HIV-positive people with mild COVID-19 did not. The result was the same in the HIV-positive group at six months, but a few HIV-negative people no longer had detectable antibodies.

All the people with HIV had memory B-cells capable of producing antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein at three months, including those without detectable IgG antibodies. (Antibody levels typically wane over time, but memory B-cells can make new ones if the virus is encountered again.) One HIV-positive person lost memory B-cells by six months.

The numbers of T-cells that produce interferon-gamma, interleukin-2 or both (cytokines that activate immune cells) were similar in HIV-positive people and HIV-negative people at three months, but HIV-negative people with severe COVID-19 had higher T-cell immune responses at six months.

These findings suggest that people with HIV develop "natural immunisation" comparable to that of HIV-negative people after recovery from COVID-19, the researchers concluded. What's more, there appears to be a correlation between more severe COVID-19 and the strength of both humoral and cellular adaptive immunity at six months.

Further, Tiraboschi added, a significant proportion of SARS-CoV-2-specific B-cells were detected among HIV-positive individuals without antibodies, which suggests that a "robust" antibody response could be triggered upon viral re-challenge in this group.

In a related study, Dr Maria Laura Polo of Instituto INBIRS in Buenos Aires and colleagues evaluated SARS-CoV-2 immunity in people who had recovered from COVID-19. They analysed blood samples donated to the Argentinean Biobank of Infectious Diseases from 21 HIV-positive people with an undetectable viral load on ART and 21 HIV-negative individuals who were diagnosed with mild-to-moderate COVID-19. The median ages of the two groups were 47 and 41 years, respectively. The HIV-positive group had a median CD4 T-cell count of 554 cells/mm3 and a median CD8 count of 605 cells/mm3.

The researchers measured levels of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies and how well they worked against the original (wild-type) SARS-CoV-2 strain, as well as assessing SARS-COV-2-specific T-cell responses. They used flow cytometry to measure the number of T-cells, B-cells and natural killer (NK) cells, the latter of which provide a first line of defence until virus-specific immune cells go into action.

They found that 75% of people with HIV and 85% of HIV-negative people had detectable SARS-CoV-2 antibodies; IgG levels did not differ significantly between the two groups. In the HIV-positive group, antibody neutralisation capacity was correlated with IgG levels and CD4 and CD8 T-cell counts. There was no significant difference in the number of B-cells, but HIV-positive people had fewer antibody-secreting cells.

All the donors had evidence of cellular immunity against SARS-CoV-2, though responses in the HIV-positive group were weaker and less broad. Both groups generally had similar numbers and types of naive and memory CD4 and CD8 T-cells, including regulatory T-cells (which suppress overactive immune responses), but HIV-positive people had a higher proportion of T-follicular helper cells (which help B-cells produce antibodies).

However, the two groups showed some differences in functional markers on immune cells, with HIV-positive people having higher expression of PD-1 (a marker of T-cell exhaustion) on CD4 cells, HLA-DR (a marker of T-cell activation) on CD8 cells and several different markers on NK cells.

"Although people living with HIV showed an immune profile with enhanced activation and exhaustion, severity of COVID-19 was not exacerbated," the researchers concluded. People with HIV "could elicit SARS-CoV-2-specific cellular responses" but these were lower than those of HIV-negative individuals.

In people with HIV, a preserved CD4 T-cell count emerged as a key factor in achieving better antibody responses with higher neutralisation capacity, Polo reported, suggesting that ART not only controls HIV but also improves the ability to control other infections.

Emphasising the importance of HIV treatment, another research team recently described the case of a South African woman with uncontrolled HIV and a CD4 count below 20 who took more than 200 days to clear SARS-CoV-2 (published as a preprint). This usually takes at most a few weeks. During that time, the virus mutated extensively within her body. Only after she switched to effective ART did she finally clear the coronavirus.

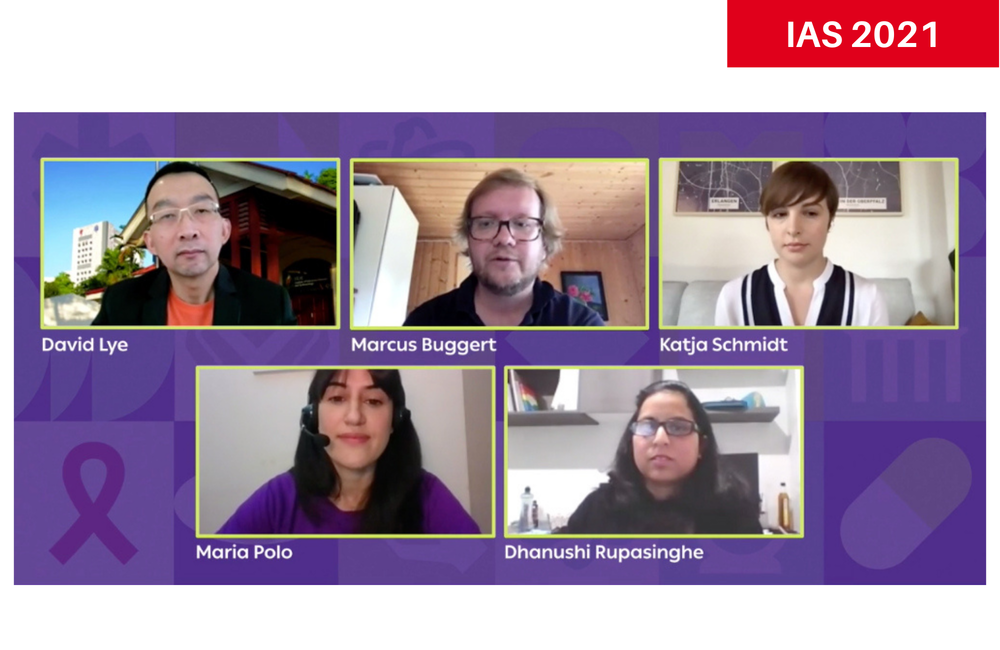

Session moderator Professor Marcus Buggert of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm asked Polo whether her findings have implications for COVID vaccine response among people with HIV.

"From what we saw, we think that people living with HIV will be able to elicit robust responses to vaccination," she said, noting that her team is now studying vaccine responses in HIV-positive and HIV-negative people using the Russian Sputnik vaccine, which is the most widely available in Argentina.

Anecdotally, Buggert noted that he is seeing the same thing, suggesting that most people with HIV seem to respond fine in comparison to other immune-deficient risk groups like organ transplant recipients, and that those with higher CD4 counts appear to respond a little bit better.

Polo ML et al. SARS-Cov-2 immunity in COVID-19 convalescent individuals living with HIV: bulk immune profiling and SARS-CoV-2 specific humoral and cellular immune responses. 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science, abstract OALA0101, 2021.

Tiraboschi J et al. Robust SARS-CoV-2-specific serological and functional t-cell immunity in PLWHIV. 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science, abstract OAB0101, 2021.

Karim F et al. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection and intra-host evolution in association with advanced HIV infection. MedRxiv preprint, 4 June 2021.