The long-acting injectable HIV medications cabotegravir and rilpivirine, which are administered by a healthcare provider once a month, can be successfully implemented in health practises in the United States, according to a study presented at the 11th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2021). What's more, providers and people with HIV encountered few barriers to giving or receiving the injections despite changes in health services during COVID-19.

"Over the course of a year, even with the added challenges of COVID-19, the barriers that providers and patients thought they would face turned out not to be as concerning as originally thought," Dr Maggie Czarnogorski of ViiV Healthcare said in a press release.

In October 2020, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved the injectable combination regimen, which consists of an extended-release formulation of ViiV Healthcare's new integrase inhibitor cabotegravir (Vocabria) plus an injectable version of Janssen’s non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor rilpivirine (Rekambys, sold in pill form as Edurant). The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the combination, sold in North America as Cabenuva, in January 2021.

The phase 3 ATLAS and FLAIR trials showed that monthly injections of cabotegravir plus rilpivirine maintained viral suppression as well as a standard oral regimen. The ATLAS-2M study showed that administration every other month works as well as monthly injections. (The FDA has approved only once-monthly administration while the EMA approved both a monthly and a bimonthly schedule.)

Across these studies, participants said they preferred the monthly or bimonthly injections over daily pills. Mild to moderate injection site reactions are a common side effect, but these diminish over time and recipients found them acceptable.

However, some have raised questions about whether HIV care providers and clinics have the resources to administer a monthly or bimonthly injectable treatment. The regimen involves two jabs in the buttocks given during the same clinic visit. It is not approved for self-administration at home.

Czarnogorski presented results from the phase 3 CUSTOMIZE study, which assessed barriers to and effective strategies for successful implementation of the injectable regimen in US clinical practice settings.

Twenty-four healthcare staff members at eight US clinics, including physicians, nurses, administrators and front desk staff, completed surveys at the start of the study and again four months and a year later. Clinic types included two federally qualified health centres (which serve low-income people), two university practices, two private practices, one AIDS Healthcare Foundation clinic and one health maintenance organization (HMO). Five of the clinics were located in the southeast, which bears the brunt of the US HIV epidemic, two were in the midwest and one was in California. In addition, people who received the injections were surveyed on the same schedule.

Overall, both healthcare staff and recipients found the injectable regimen acceptable and feasible.

"Feasibility ratings rose as clinics established procedures and became accustomed to giving the injections."

Among the staff, 91%, 92% and 98% rated the regimen as acceptable at the start of the study and at month 4 and month 12, respectively. In general, acceptability was high across all types of clinics, except for the HMO, where acceptability declined from 92% initially to 67% at months 4 and 12.

Looking at feasibility, most healthcare staff predicted that implementation would be possible at the start of the study. At the outset, predicted barriers included concerns about patients' ability to keep monthly appointments and obtain transportation, questions about how to flag and reschedule missed visits, and inadequate staff resources.

Perceived feasibility declined somewhat at month 4, as healthcare staff realised some adjustments may be needed in the clinic, Czarnogorski reported. But feasibility ratings rose again and perceived barriers decreased by week 12, as clinics established procedures and became accustomed to giving the injections. This occurred despite disruptions related to COVID-19. Although just 63% of staff initially predicted that the injections would be easy to administer, this rose to 91% by month 12.

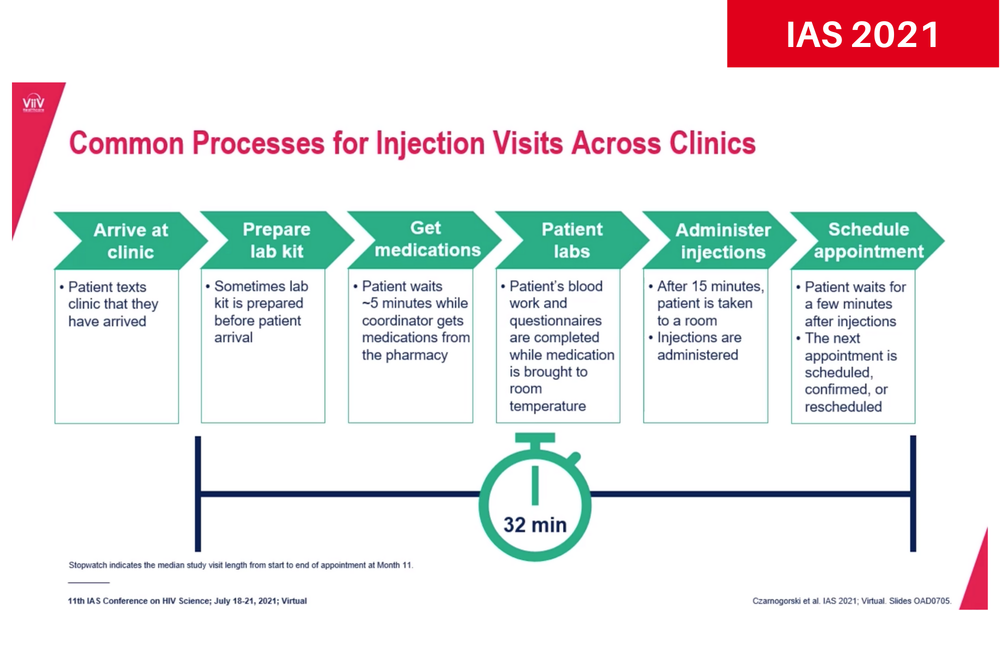

More than three-quarters of clinic staff members said it took one to three months to implement the injectable regimen, while 17% said it took four to six months and 4% said it took seven to nine months. A typical process for preparing for and administering the injections took about a half hour. Some of the changes made to accommodate the new regimen included extended clinic hours, allocating rooms for injections, increased co-ordination with other departments and purchasing new refrigerators for the medications.

Asked about strategies that facilitated successful implementation, respondents cited good staff communication, teamwork and use of a web-based treatment planner. A majority of staff members (70%) said that monthly visits provided other benefits to patients such as improved engagement with healthcare providers, greater awareness of their health, increased monitoring for high-risk individuals and added opportunities to screen for sexually transmitted infections, advise people about alcohol use and remind them about routine care. Some staff members said that patients' enthusiasm about the new regimen was key to successful implementation.

Among the more than 100 injection recipients surveyed, 94% rated the regimen as acceptable at the start of the study and at month 4, rising to 98% at month 12. Most found monthly visits and the amount of time spent in the clinic to be acceptable. More than 90% preferred the injections to their previous daily oral therapy, and 97% intended to continue on the long-acting regimen. All participants maintained viral suppression over the course of the yearlong study.

Injection pain or soreness was the most frequently cited factor that interfered with the ability to keep taking the regimen, but this was reported by only 15%. Most said appointment reminder calls and texts were helpful. Patients reported fewer barriers than providers, and by 12 months, 74% said nothing interfered with their ability to receive injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine.

"CUSTOMIZE demonstrates that [long-acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine] can be successfully implemented across a wide range of US healthcare settings and was perceived as a convenient and appealing alternative treatment option by healthcare providers and people living with HIV," the researchers concluded.

Czarnogorski M et al. CUSTOMIZE: overall results from a hybrid III implementation-effectiveness study examining implementation of cabotegravir and rilpivirine long-acting injectable for HIV treatment in US healthcare settings; final patient and provider data. 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science, abstract no OAD0705, 2021.

Czarnogorski M et al. CAB+RPV LA implementation outcomes and acceptability of monthly clinic visits improved during COVID-19 pandemic across US healthcare clinics (CUSTOMIZE: hybrid III implementation-effectiveness study). 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science, abstract no PED463, 2021.

Correction: this article was corrected on 21 July 2021. The study assessed the implementation of monthly injections; the every other month schedule was not used in this study.