A new formulation of the drug islatravir in the form of a small removable implant should provide enough drug to act as PrEP or form part of combination antiretroviral therapy for well over a year, the virtual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) heard yesterday.

The study is similar to one presented in 2019 by the same researcher, Dr Randolph Matthews of Merck, the company that is developing islatravir. He said a second phase I drug-level and safety study was necessary because the new formulation of the implant is the one that is now going to be taken forward into a phase II study: the previous one was just a proof-of-concept pilot.

The main difference with the new formulation is that it contains a small amount of the non-toxic metallic element barium, as do contraceptive implants like Nexplanon. Barium is opaque to X-rays and so is used as a contrast medium in gut X-rays. Implants such as the planned one can occasionally ‘migrate’ away from their original site and may need to be located and removed.

The new formulation of the implant contains slightly less drug than the implants tested two years ago. In that study the implants contained a total of ether 54mg or 62mg of drug. In the new study three doses were used, of 48mg, 52mg and 56mg.

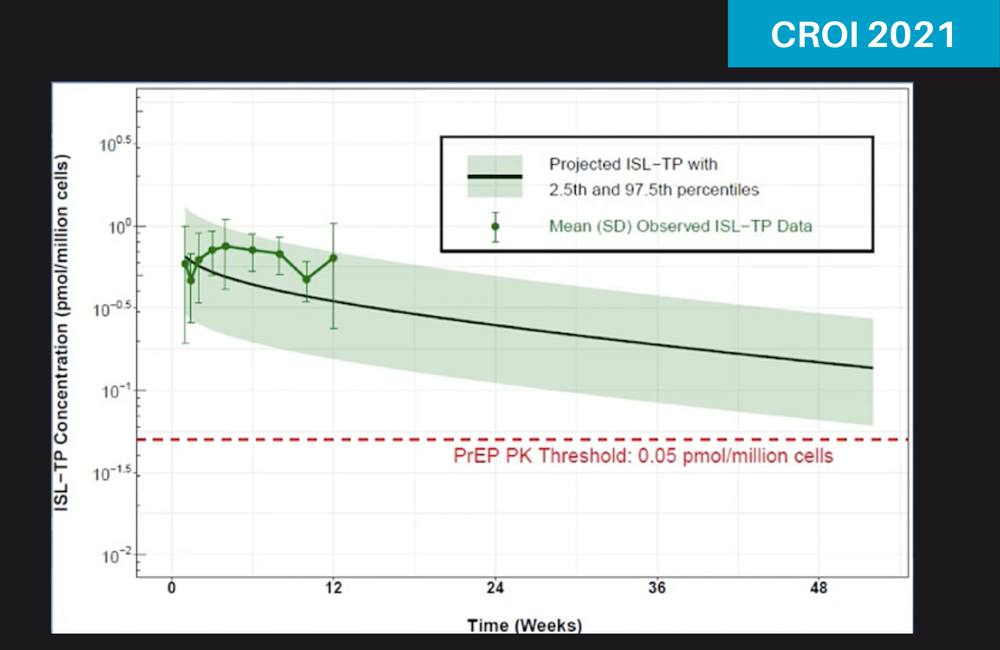

At the same conference session, Merck’s Dr Munjal Patel said that a level of 0.05 picomols of drug per million circulating T-lymphocyte immune cells (0.05 pmols/106 cells) should be more than adequate for preventing HIV infection. This level was determined by looking at results from three different studies: one of islatravir-treated human volunteers whose lymphocytes were extracted and then exposed to HIV in the lab dish; one which exposed monkeys to an artificial monkey-adapted HIV virus; and one of the initial studies in which islatravir’s ability to inhibit HIV replication in cells was directly measured.

The results from these studies indicated respectively that the 0.05 pmols/106 cells level was respectively five times, 1.6 times, and 2.5 times above the level to stop HIV infection in people with the lowest drug levels.

In the latest phase I study, 24 volunteers were given islatravir implants (eight volunteers for each of the three doses) and 12 volunteers given a placebo implant not containing drug. The volunteers kept the implants in for three months, after which they were removed.

After removal, the intracellular half-life of the remaining islatravir in the body (the rate at which it tailed off) was 198 hours, meaning that after 8.5 days there was half as much drug left as when the implant was removed, and after just over a month there was one-eighth as much. This intracellular half-life is about the same as that of oral islatravir.

In the two smaller doses, drug concentrations persisted above the 0.05 pmols/106 cells level for no more than two weeks but in the largest dose they persisted for one to two months. Matthews said this did not pose the same kind of ‘long tail’ problem of persistence in the body as injectable cabotegravir could of possible resistance arising if people were exposed to HIV during the period the drug levels decayed. In fact, the half-life observed was no longer than that of intracellular tenofovir once a steady-state level of drug had been reached in cells.

Side effects were common, but almost all mild. In volunteers given the placebo implant, half of volunteers had some side effects, whereas two-thirds of volunteers given islatravir-containing implants had some. These included redness, pain or itching at the implant site and also induration, or hardening of tissue around the implant. There were three instances of side effects classed as moderate rather than mild: two of redness and one of itching. There were no side effects classed as serious and no discontinuations due to side effects.

Clearly this study cannot demonstrate real-life drug levels after the implant had been in a year, but projections from this three-month study predict that after a year, the average drug level in people using it would still be 3-4 times above the 0.05 pmols/106 cells level. It should be more than 20% above this level in all but 2.5% of users. However, these are models and one reason a phase II study is needed is to see if real-life levels are the same as forecast.

Matthews said that the planned phase II study will be very similar to the study of islatravir given as a once-a-month pill whose results were presented at last month’s HIVR4P conference. As with that study, it will be conducted among people at low risk of HIV because the main question Merck wishes to answer is whether dug levels will in fact persist for well over a year at levels sufficiently high to prevent HIV infection.

Following the conference, on March 15, Gilead and Merck announced a collaboration to jointly develop long-acting combinations of lenacapavir and islatravir for HIV treatment.

Matthews R et al. Next-generation islatravir implants projected to provide yearly HIV prophylaxis. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, abstract 88, 2021.

Patel M et al. Islatravir PK thresholds & dose selection for monthly oral HIV-1 PrEP. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, abstract 87, 2021.