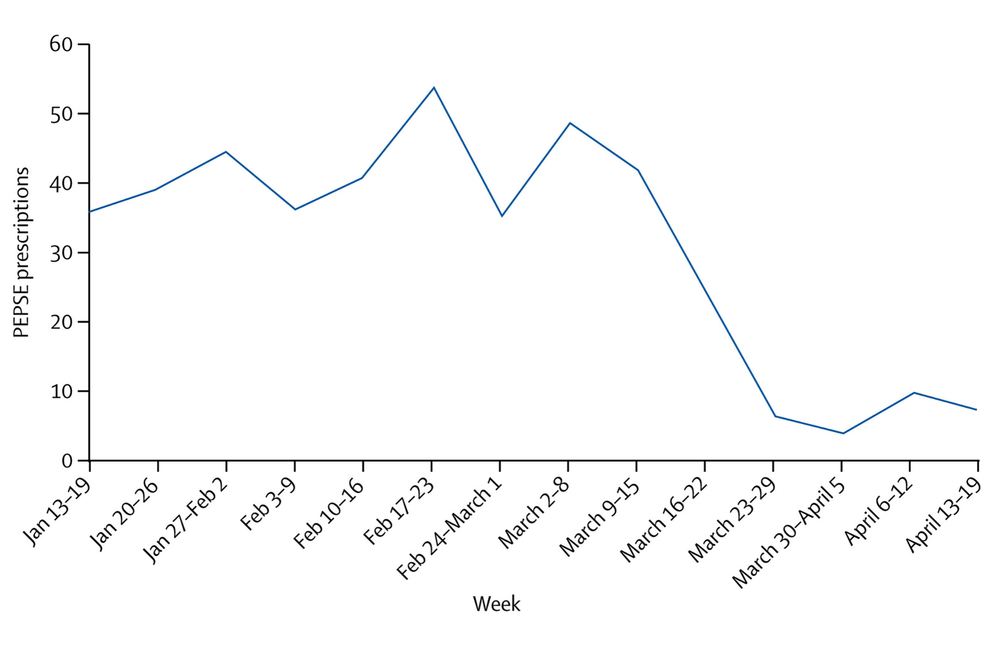

According to figures just published in The Lancet HIV, prescriptions for HIV post-exposure prophlyaxis (PEP) at the largest HIV and sexual health clinic in Europe, 56 Dean Street in London, fell from an average of 40 a week in January, to seven a week in April, after lockdown for COVID-19 was instituted on 23 March.

This represents an 82.5% decline in PEP prescriptions, or a nearly sixfold fall.

PEP for sexual exposure is a four-week course of HIV drugs that may prevent HIV infection if they are started within 48 hours after a likely exposure to HIV. See here for more information.

Muhammad Junejo and colleagues, in The Lancet HIV article, note that 56 Dean Street accounts for a quarter of the 12,000 PEP prescriptions dispensed in England every year. Although many sexual health services have had to be withdrawn or limited during the COVID-19 crisis, and local clinics closed, 56 Dean Street has continued to offer PEP as a walk-in service.

PEP prescriptions were starting to fall even before the lockdown and then fell precipitately. From a peak so far this year of 54 prescriptions in the week starting 17 February, and an average of 41 during a four-week period starting 20 January, they fell to 22 in the week immediately before lockdown. In the four weeks after lockdown, there was an average of four a week.

The people coming for PEP and their reasons for seeking it have, by and large, not changed since lockdown, despite the lower figures. Their average age was 32 and the vast majority were men.

The vast majority were seeking it for anal sex between men and most because they had been the receptive partner, though there was an apparent, but statistically non-significant, increase in insertive partners seeking it during post-lockdown (29% post-lockdown versus 12% before). About a quarter of prescriptions were for group sex situations, before and after lockdown.

However, there was a statistically significant increase in the proportion of PEP requests coming from people who’d had chemsex (sex involving methamphetamine, mephedrone, ketamine and/or GBH/GBL), if not in the absolute numbers. In the pre-lockdown period, 28 prescriptions (17%) involved people who’d had chemsex, compared to eleven (39%) in the post-lockdown period.

Junejo and colleagues comment that the sharp decline in PEP prescriptions might be due to people having less sex that involves HIV exposure, or it might be due to people being afraid to attend a clinic during lockdown – possibly a mixture of the two.

If, however, at least some of it is due to people having less exposure to HIV, then the opportunity exists to break the chain of HIV transmission in the gay community. Now that lockdown has been in place for well over four weeks, any infections that happened more than four weeks ago will be detected by a standard fourth-generation HIV test. If people who may have caught HIV prior to lockdown do get tested, then they can take treatment and be taken out of the pool of people who are still infectious, in what is already a period of historically low transmission. They won’t be infectious when lockdown ends and people start having sex again.

56 Dean Street has therefore launched a social media campaign at www.testnowstophiv.com to encourage people to order HIV home-testing kits, even if they currently don’t feel at risk, to try and reduce any chance of a flare-up in HIV when the lockdown ends.

Junejo M et al. HIV postexposure prophylaxis during COVID-19. Lancet HIV, online ahead of print, 25 May 2020.