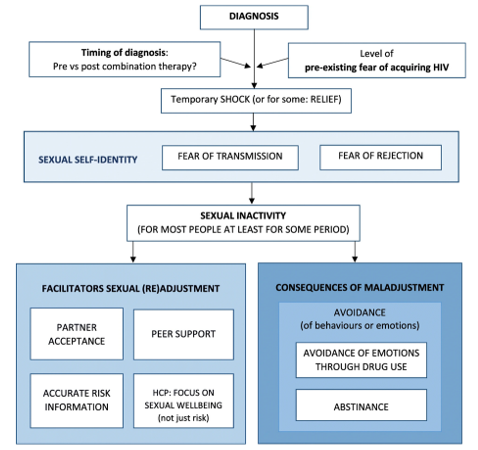

For people living with HIV, sexual adjustment after diagnosis is affected by fears of transmitting the virus and of possible rejection by sexual partners, new qualitative research shows. Healthy sexual adjustment over time is facilitated by partner acceptance; peer, community and professional support; and up-to-date knowledge of HIV transmission, including U=U.

Barriers to healthy sexual adjustment include the persistence of undue fears of transmission and rejection long after diagnosis, which may result in avoiding sex or pairing it with drugs and alcohol. Based on these findings, Dr Ben Huntingdon and colleagues at the University of Sydney propose a new model of sexual adjustment to HIV, published in the BMC Infectious Diseases journal.

With the current global focus on early diagnosis and treatment of HIV, those living with HIV on successful treatment are expected to have near-normal life expectancy. This requires a shift in focus from survival to quality of life, including sexual satisfaction and adjustment after an HIV diagnosis. Previously, research into the sex lives of those living with HIV focused on managing the risk of onward transmission (primarily through condom use) and disclosure of status to sexual partners.

There has been little research looking at factors that facilitate or inhibit sexual adjustment after an HIV diagnosis. This is important in light of biomedical advances, especially 'Undetectable = Untransmittable' (or U=U, meaning that those on successful treatment with an undetectable viral load cannot pass the virus on).

The study

Recruitment was conducted at two public HIV clinics in Sydney and via community groups. Adults with an HIV diagnosis living in Australia were eligible for inclusion. Questionnaires collected demographic information and data on depression, anxiety and sexual satisfaction, before a semi-structured phone interview.

Nineteen men and ten women took part. Their average age was 42, with an average of 10 years since diagnosis (range: 1-30), 57% were single, with 37% married or in relationships. Participants had been on treatment for an average of around eight years, with 87% reporting an undetectable viral load. Most participants were employed (63%) and just under half had a tertiary or post-graduate degree. Two-thirds of the sample identified as gay and just over half were born in Australia.

Psychological distress scores were in the mild-moderate range for just under half of the participants, with ten participants having severe to extremely severe scores. Sexual wellbeing scores were average or above average for 43% of the sample.

Positive sexual adjustment was defined by sexual activity that the participant was satisfied with. Negative sexual adjustment was defined by significant barriers to sexual activity, as a result of HIV status, which left the participant feeling dissatisfied.

Initial reactions to diagnosis

After diagnosis, three distinct sexual behaviour patterns that emerged: sexual inactivity, no change to sex life or an increase in sexual activity.

Most participants fell into the first category and described stopping sexual activity upon receiving their diagnosis. This was largely determined by fear of transmitting the virus to a sexual partner and fear of rejection upon disclosure.

“After diagnosis I was actually scared shitless to have sex with anyone. I thought: 'No. That's it, I'm never having sex with anybody ever again’.” – Female, diagnosed late 2000s.

“Fear of having to tell someone that you’re HIV-positive – I think that was the predominant factor [related to sexual inactivity] for me.” – Female, diagnosed early 2010s.

Some participants (often those in long-term relationships with accepting partners) reported no change to their sex lives.

“It was good, we were just married, so we were having sex quite often. Just normal sex.” – Female, diagnosed early 2010s.

Other participants, all of whom were male, described an increase in sexual activity after receiving their diagnosis. They spoke of having condomless sex with other HIV-positive partners (serosorting) as a liberating experience, free of the fear of contracting HIV.

“There was this exploration … [within my sex life] I didn't have before … It was a bit more exciting and I was being a bit more extreme and doing things [sexual practices] that I didn't do before [I had HIV].” – Male, diagnosed late 2000s.

Facilitators of sexual adjustment

A variety of factors contributed towards positive sexual adjustment after the initial shock of diagnosis wore off. One could be a partner’s accepting response to an HIV diagnosis: this was a strong indicator of later positive sexual adjustment for the HIV-positive partner.

“I told him [I was HIV positive] after our first date. I remember I couldn’t look at him so I turned away, and I just felt him lean across and put his head on my shoulder and say he didn’t care; he just wanted to be with me…” – Female, diagnosed late 1990s.

"A partner who was willing to have sex without fully acknowledging the HIV and who glossed over fears of transmission did not facilitate positive adjustment."

However, this was a complex process that was not always clear-cut. At the one extreme, outright rejection by a long-term partner would severely impact upon subsequent sexual adjustment. A partner who showed excessive fear around sex and who was overly cautious would also contribute negatively towards sexual adjustment.

However, a partner who was willing to have sex without fully acknowledging the HIV and who glossed over fears of transmission did not facilitate positive adjustment either. For adjustment to occur, the partner needed to acknowledge HIV as part of the individual while not showing undue fear. Some participants described this as an ongoing process as opposed to a one-off event.

“I was very scared of giving [HIV] to my husband. He wouldn’t use protection and he said he loved me and if he caught it so be it … I tried to avoid the situation…” – Female, diagnosed mid-2000s.

“The first time, he was wearing two condoms … he was wearing gloves to touch me … I think he was scared and I think he still is scared about it … I was always feeling a little bit low because of that.” – Female, diagnosed early 2000s.

Only having sex with other HIV-positive people facilitated adjustment for some interviewees:

“[By serosorting] you don’t have to worry about disclosing [having HIV] … or even the possibility of infecting someone else…” – Male, diagnosed mid-2010s.

Some participants expressed that although they initially only selected other HIV-positive partners, these interactions gave them confidence to later seek out HIV-negative partners. The authors suggest that serosorting may help people adapt in the short-term but is not necessarily a healthy long-term strategy as it could be overly limiting.

Peer and community support could be helpful:

“I got to meet other [HIV-]positive guys, especially the older ones and just sort of learnt from their experience…it helped with that self-acceptance...” – Male, diagnosed mid-2010s

“It does wonders for your mental health and knowing that you can’t transmit the virus."

Accurate knowledge of transmission risks (especially in light of U=U and PrEP) was an important factor for many:

“It does wonders for your mental health and knowing that you can’t transmit the virus … I was so terrified of transmitting [the virus] and too terrified to tell people I had HIV. [An undetectable viral load] has allowed me to not only tell people but it’s allowed me to truly, for the first time in my life, negotiate the type of sex that I want to be having.” – Male, diagnosed late 2000s.

Health professionals facilitated sexual adjustment when they demonstrated that they cared about a person’s sexual wellbeing and not just sexual risk:

“My first doctor… was incredibly good; she asked me if I was having a healthy sex life. My partner… was quite hypersensitive about risk. She called him in and talked him through what was risky and what wasn’t.” – Male, diagnosed late 2000s.

Barriers to sexual adjustment

Participants who spoke of ongoing difficulties with sexual adjustment post-diagnosis often displayed persistent fears of transmission and rejection. Some were aware of U=U but their fears persisted – their conditioned thinking around risk proved resistant to change. Others had been given conflicting medical advice.

“I still worry [about HIV transmission]. I’ve gone to workshops … and I’ve read about it a lot … even if I’m doing it the absolute safest way to have sex, I still worry…” – Male, diagnosed mid-2010s.

Some participants actively avoided situations involving sexual intimacy or had no sexual activity.

"Some used drugs and alcohol to deal with fears and emotions associated with sex."

“I think it’s all mental really … I don’t put myself out there. There’s a real fear of rejection and openness because of the need to disclose. There has been rejection and all those things before and that feeds back into not seeking any sort of sexual activity with anyone.” – Male, diagnosed mid-2000s.

Some individuals used drugs and alcohol to deal with fears and emotions associated with sex, but this often contributed to worse outcomes.

“I had become depressed and the more drugs I was using [to have sex], the more depressed I was becoming. That’s the cycle of taking drugs and having crazy sex to make yourself feel better and you feel good for a while. The reverse is that you feel even worse about yourself and more depressed.” – Male, diagnosed early 2010s.

Conclusion

The authors conclude by presenting a process model of sexual adjustment to HIV. They emphasise the potential benefits this model may have in clinical settings with those living with HIV: “By using this model of facilitators and barriers, health professionals can promote sexual adjustment and good overall sexual quality of life of people living with HIV.”

Image credit: Diagrammatic model of the process of sexual adjustment to HIV resulting from this analysis.

Huntingdon B et al. A new grounded theory model of sexual adjustment to HIV: facilitators of sexual adjustment and recommendations for clinical practice. BMC Infectious Diseases 20: 31, 2020 (open access).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4727-3