The nucleoside (NRTI) drug abacavir (Ziagen also in Kivexa/Epzicom) continues to be associated with a near-doubling of the risk of a heart attack, according to the latest update from the Data Collection on Adverse events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study, presented to the 21st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI).

In March 2008 the D:A:D study, a collaboration of eleven prospective cohorts from across Europe, Australia, and the US, totalling over 30,000 participants, first published results showing an almost doubled risk of heart attack in people taking abacavir.

While subsequent updates from D:A:D and some other studies have also found evidence of a link between abacavir and heart attacks, some other studies, including a meta-analysis by the US Food and Drug Administration, have found no evidence of increased risk. D:A:D’s own evidence suggests the increased risk is only significant in people who already have risk factors for a heart attack, a finding possibly confirmed by some studies that show abacavir is associated with inflammatory changes in the blood vessels that are also associated with HIV infection itself. Other studies have failed to find such changes, however, or have found that traditional risk factors for heart attack lie behind the apparent increase in risk associated with abacavir.

The question is still not settled, with the latest D:A:D data presented at last week’s conference still reporting that abacavir is associated with a doubling of the risk of heart attack in people taking it.

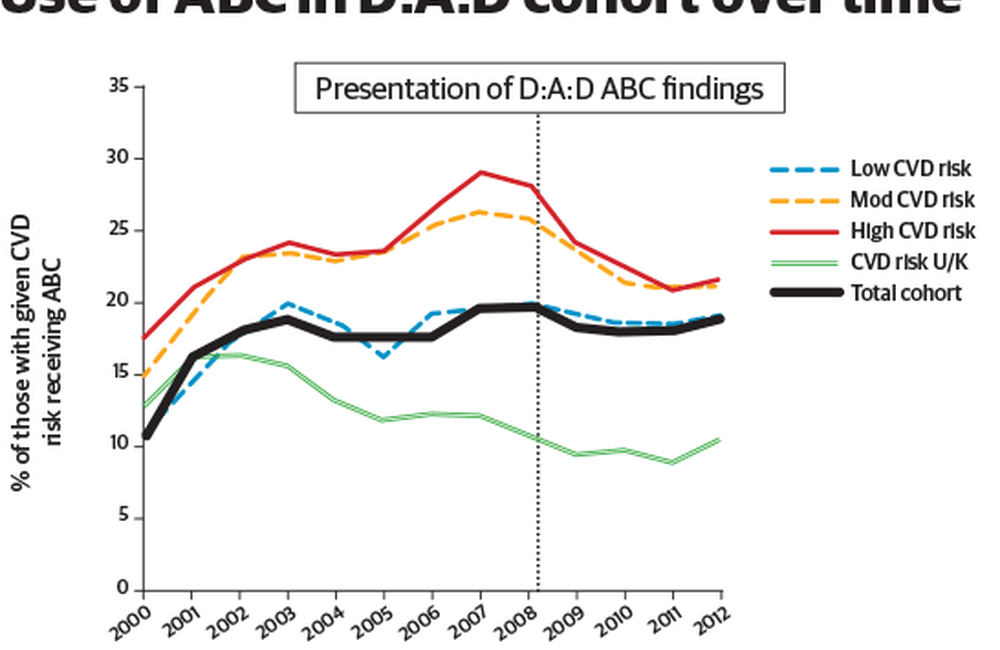

The D:A:D study found that the use of abacavir in its cohorts increased from 10% in 2000 to 20% in 2008, before stabilising at 18-19%. Increases in use prior to March 2008, when the apparent risk was first isolated in D:A:D, and subsequent decreases, were greatest in those at moderate and high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Post-March 2008, those taking abacavir who were at moderate to high risk of cardiovascular disease were more likely to discontinue the drug than those at low risk, regardless of viral load; no such associations were seen before March 2008.

After March 2008, treatment-naive people at moderate to high CVD risk were 26% less likely to initiate abacavir than those at low or unknown CVD risk, though this difference was not statistically significant

Why is this usage pattern important? One suggestion about why abacavir was associated with CVD is that the drug’s use was affected by so-called ‘channeling bias’. In this, a treatment’s apparent link with an adverse effect is actually caused by an unaccounted-for factor that produces more use of this treatment in people who share the hidden factor – and it is this factor that increases the adverse effect shown, not the drug.

In abacavir’s case, it was hypothesised that, pre-2008, people more prone to CVD were also more likely to be prescribed abacavir than its rival drug tenofovir (Viread, also in Truvada, Atripla and Eviplera). This is because of tenofovir’s well-known association with kidney dysfunction – which both causes, and is caused by, high blood pressure. This could be a reason why people more prone to CVD – a primary cause of which is high blood pressure – could be more likely to be prescribed abacavir.

Since 2008, however, people with more CVD risk factors were less likely to be prescribed abacavir. Despite this, the excess risk of heart attack has persisted.

By 1st February 2013, 941 heart attacks had occurred in 367,559 person-years in the D:A:D study – a rate of about one heart attack per 400 patients a year (0.26%).

The rate of heart attacks was 0.47% – nearly one in 200 per year – in people currently taking abacavir but less than half that – 0.21% – in people not taking it. This means that current abacavir use was associated with a 98% increase in heart attack rate – an increased risk remarkably unchanged since the first report in 2008. This found a 90% increased risk which, after re-analysis, is now found to be a 97% increased risk.

These results were unchanged after adjusting for factors that could potentially be associated with heart attacks such as kidney function, high blood pressure and high blood fats, even though fewer patients with high heart attack risk were being prescribed abacavir.

No cohort study can completely rule out the possibility that some unmeasured confounder might produce the results seen instead of the association noted. However, these figures do seem to make one of the explanations for the increased risk of heart attack in people taking abacavir look unlikely.

Sabin C et al. Is there continued evidence for an association between abacavir and myocardial infarction risk? 21st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, abstract 747LB, 2014.