There are significant losses at each step of the post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) ‘treatment cascade’, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis of 97 studies presented to the 20th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2014) in Melbourne yesterday. The problems with uptake, adherence and completion point to a need for a simplified approach, comment the authors.

PEP is a 28-day course of two or more antiretroviral drugs, taken by HIV-negative individuals who believe they may have been exposed to HIV, for example after a needlestick injury in a healthcare facility, when a condom has split, or following sexual assault.

Nathan Ford and colleagues from the World Health Organization identified all studies of PEP that reported on completion rates and pooled their data. Information about 21,462 individuals in 97 separate studies was included.

The majority of data (68 studies) were from high-income countries, with fewer reports from low- and middle-income countries. Most studies concerned PEP following sexual or other non-occupational exposure, but there were also data on occupational exposure and sexual assault. A quarter of studies included data on children or adolescents.

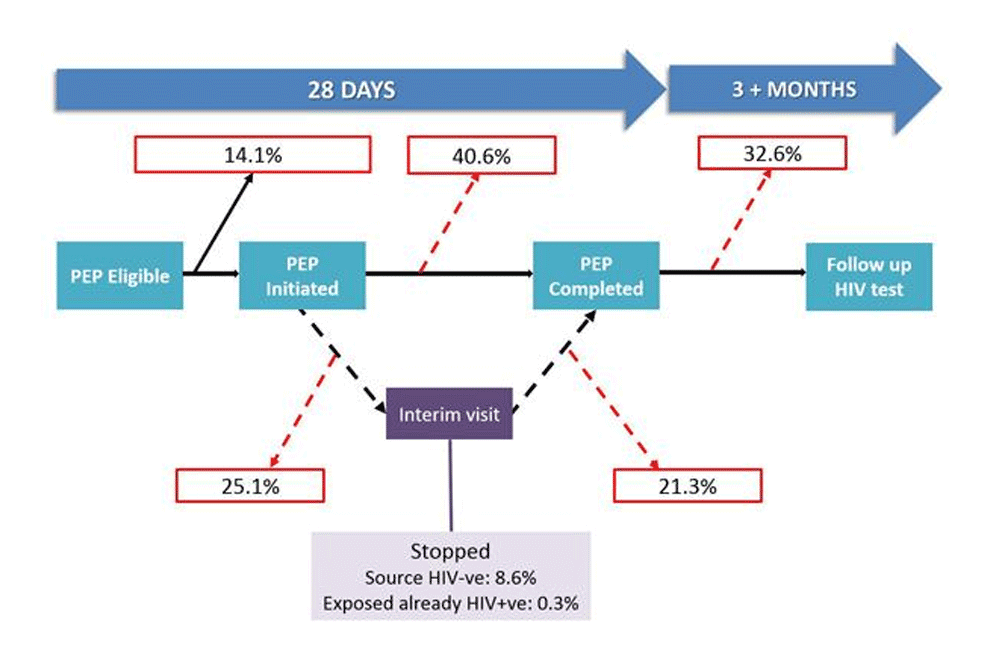

Of individuals who were assessed by a healthcare provider and judged to be eligible for PEP, 14% chose not to take it. Of all individuals starting PEP (and not subsequently judged to be ineligible), only 56.6% completed the 28-day course.

Completion was poor for all populations and for all types of exposure. However, it was especially low among female sex workers (48.8%) and victims of sexual assault (40.2%).

Of those who completed the course, 31.1% failed to attend for a follow-up visit that would include HIV testing.

Whereas some programmes give individuals the drugs for the full 28 days of treatment, others initially offer a partial prescription (sometimes called a ‘starter pack’) and require individuals to return to the healthcare facility for more. Starter packs were most commonly provided for cases of non-occupational exposure or sexual assault. However, fewer people given starter packs completed the course (53.2%) than people given the full course (70.0%). Over a quarter of those given a starter pack failed to return for the rest of the prescription.

Interventions to improve uptake and retention, and a simplified approach, are needed, say the authors. They also say that the problems with PEP give insight into the challenges for adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which also involves HIV-negative people taking antiretroviral drugs.

Ford N et al. Adherence to PEP along the cascade of care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 20th International AIDS Conference, Melbourne, abstract TUPE153, 2014.

View this abstract on the conference website.

Ford N et al. Variation in adherence to post-exposure prophylaxis by exposure type: a meta-analysis. 20th International AIDS Conference, Melbourne, abstract TUPE154, 2014.

View this abstract on the conference website.

Irvine C et al. Do starter packs improve outcomes for people taking HIV post-exposure prophylaxis? 20th International AIDS Conference, Melbourne, abstract TUPE155, 2014.