People with HIV and hepatitis C co-infection who delay hepatitis C treatment remain at risk for liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver-related death even after being cured – with outcomes worsening the longer it is put off – indicating that treatment should not be deferred until advanced disease, according to a presentation at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2015) last week in Seattle, USA. Treating only after progression to cirrhosis increased the risk of liver-related death by more than five-fold and the duration of infectiousness by four-fold.

Over years or decades, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection can lead to advanced liver disease including liver cirrhosis (scarring), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC; a type of primary liver cancer) and end-stage liver failure. People with HIV and HCV co-infection experience faster disease progression, on average, than those with HCV alone. Successful hepatitis C treatment reduces – but does not eliminate – the risk.

When the standard of care for chronic hepatitis C was interferon-based therapy – which was poorly tolerated, lasted up to a year and only cured about half of people with HCV genotype 1 – experts generally recommended that patients put off treatment until they experienced liver disease progression. Now that highly effective and well-tolerated direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens are available, many providers and advocates believe that everyone living with hepatitis C should be eligible for treatment. But the high cost of the new drugs has led to restrictions on their use, with some insurers and public payers only covering treatment for the sickest patients.

Cindy Zahnd from the University of Bern and fellow investigators with the Swiss HIV and Swiss Hepatitis C Cohort Studies used a mathematical model to predict the impact of different HCV treatment strategies on liver fibrosis progression among people with HIV and HCV co-infection.

The researchers fed the model data on new HCV infections among gay and bisexual men in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, who are screened annually for HCV antibodies and ALT liver enzyme levels. The model simulated patients from the time of acute HCV infection through all stages of liver disease: absent fibrosis (Metavir stage F0), mild fibrosis (F1), moderate fibrosis (F2), severe or advanced fibrosis (F3) and liver cirrhosis (F4), as well as decompensated liver disease (liver failure), liver cancer and death. They assumed that age at the time of HCV infection and alcohol consumption influenced liver disease progression.

In the initial scenario, before the advent of DAAs, the researchers assumed that 60% of patients were treated with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin, with about a 40% sustained response rate. They then ran a scenario based on interferon-free DAA regimens, assuming 100% of patients were treated with an efficacy of about 90%.

The researched then looked the model's predictions about occurrence of liver-related events and death, as well as the duration of infectiousness (i.e. having detectable HCV RNA), comparing the strategies of treating all patients one month after HCV diagnosis (not necessarily one month after actual time of HCV infection), one year after diagnosis or as they reached liver disease stages F2, F3 or F4. They did not take into account the potential for HCV reinfection after successful treatment, which can be substantial in some high-risk groups.

In the initial scenario, about 10% of patients experienced liver decompensation, more than 15% developed HCC and more than 25% died of liver-related complications.

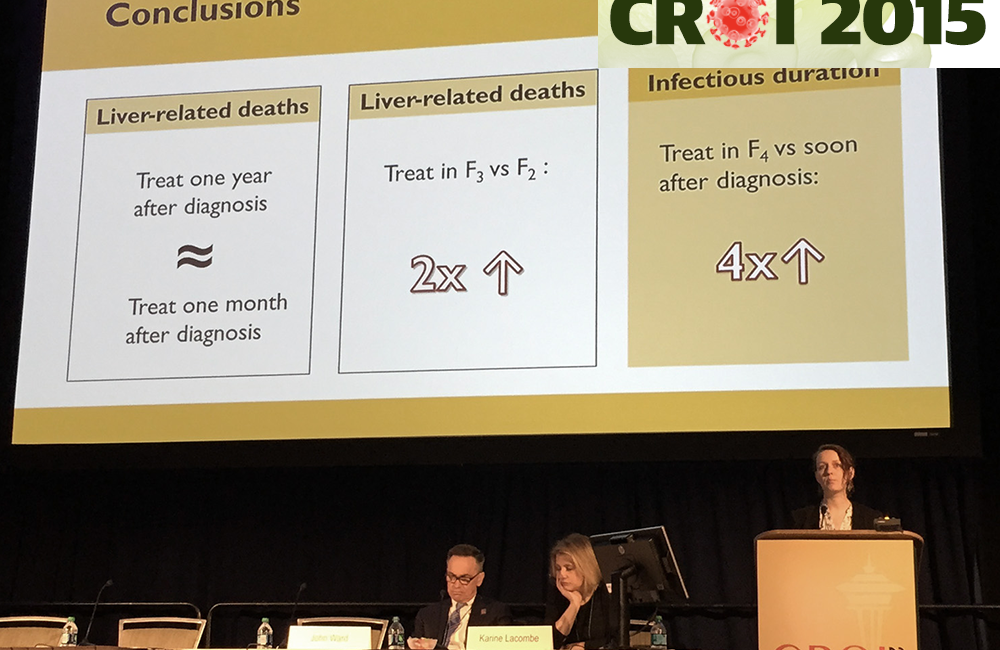

Using new DAA regimens, the model found that treatment started at one month or one year after diagnosis dramatically reduced the proportions of people with decompensation (around 1%), HCC (around 2%) and liver-related death (around 3%), with almost no difference between one month and one year.

Starting treatment at liver disease stages F2 or F3 gradually increased the risk of liver-related events and death, with a steeper jump if treatment was deferred until stage F4. For those starting treatment at stage F3, the rate of decompensation was about 3%, the rate of HCC about 8% and the rate of liver-related death about 10%.

For those starting at stage F4, the corresponding rates were about 5%, 20% and 25%, respectively. If treatment was deferred from stage F2 to F3, the rate of liver-related death doubled from 5% to 10%. If deferred from stage F2 to stage F4, the death rate increased by nearly five-fold to 25%.

People treated at one month or one year after diagnosis remained infectious, or able to transmit HCV, for about five years, compared to about 12 years if treated at stage F2, more than 15 years if treated at stage F3 and nearly 20 years if treated at stage F4.

Starting treating after one month versus one year "did not really make a difference," Zahnd explained, but whether treatment is started at stage F2, F3 or F4 "really matters".

Importantly, the risk of progression to decompensation, liver cancer or liver-related death did not fall to zero even after successful treatment. Some of these events occurred after HCV clearance, with post-clearance proportions increasing as treatment was further delayed. In fact, if therapy was deferred to stages F3 or F4, a majority of liver-related deaths occurred after being cured.

The remaining risk of liver complications and liver-related death after successful treatment indicates that people with HIV and HCV co-infection often "have other factors that keep them at risk of liver disease even after HCV clearance," Zahnd suggested. These may include antiretroviral drug toxicity, other co-infections or metabolic liver disease.

"Our model suggests that timely treatment of HCV infection is important," the researchers concluded. "Patients can progress to end-stage liver disease after HCV clearance if treatment is delayed until later stages of liver disease due to imperfect treatment responses and residual fibrosis progression in HIV-infected patients."

These findings provide support for a "different mental model" of when to treat HCV, David Thomas of Johns Hopkins said at a CROI press conference at which Zahnd and others described their hepatitis C studies. "We used to wait until [stage] F3 or F4 before treating. But that is changing."

After Zahnd's presentation, her colleague Hans-Jakob Furrer from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study team noted that providing evidence for earlier treatment is why they did this study. "We're using this data for discussions with governments," he said. "It is making negotiations easier – the data clearly support earlier [treatment] rollout."

Zahnd C et al. Impact of deferring HCV treatment on liver-related events in HIV+ patients. 2015 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), Seattle, abstract 150, 2015.