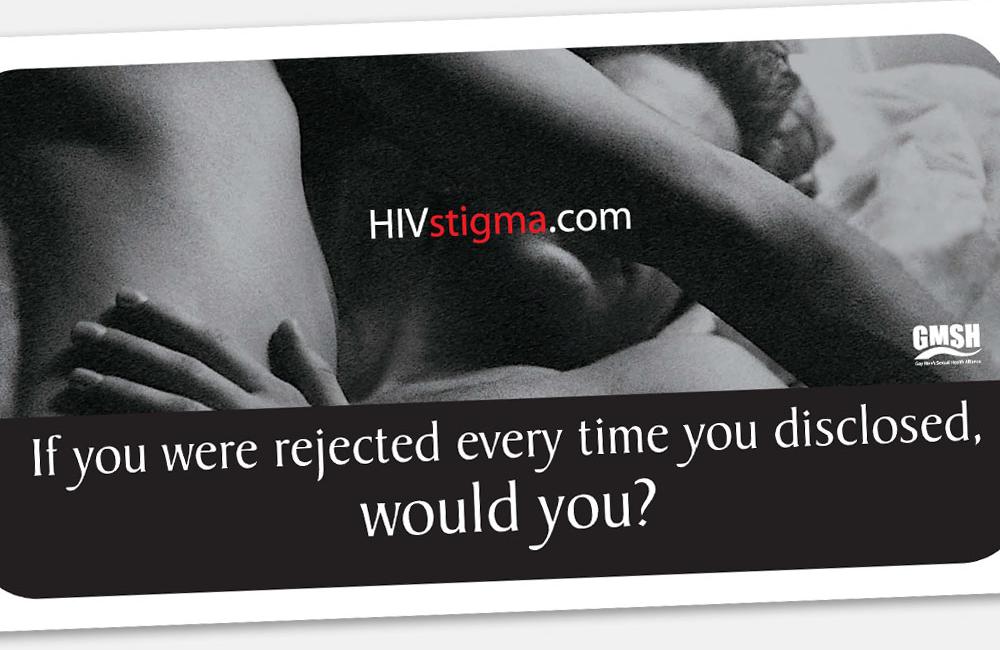

A Canadian campaign which asked gay men “If you were rejected every time you disclosed, would you?” appears to have raised men’s understanding of the dilemmas which men with HIV face. The campaign also succeeded in reducing the number of men who try to avoid infection by relying on men with HIV disclosing their status, researchers report in the October issue of Health Education Research.

The campaign was not intended to broadcast a ‘message’ or give instructions, but to stimulate dialogue within local communities. Moreover the authors suggest that the extensive community consultation which went into its development contributed to the campaign’s success.

Staff from frontline HIV prevention work, public health, government and academia participated in the consultation which identified HIV-related stigma as a priority issue. Moreover they focused on stigma within gay communities as it is manifested in the attitudes of some HIV-negative men towards potential sexual partners who have HIV. The campaign developers believe that there are links between the problems of stigma, disclosure, conflicting assumptions and risk taking.

In particular, some of those involved in this project have previously researched gay men’s sexual interactions in which “potential partners interpret risk by bringing sometimes conflicting and inaccurate assumptions to bear in making decisions about safe sex”. For example, men may make different assumptions about a partner’s willingness to have unprotected sex, with some HIV-positive men assuming that only another positive man would do so, and some HIV-negative men thinking the opposite.

To further complicate the expectations and understandings of men seeking sexual partners, the Canadian judiciary has also asserted that disclosure of HIV status is an obligation for people with HIV before any sex in which there is a significant risk of HIV transmission.

Given the incompatibility of these different assumptions, the campaign was intended to allow men to move beyond the conversations they had within their own social circles and engage in “a more broad based community discussion” about stigma, disclosure and sexual decision making.

The campaign drew attention to itself through press advertising, outdoor advertising, online promotion and community outreach activities.

It was centred on the question “If you were rejected every time you disclosed, would you?”. This question was intended to be sufficiently provocative that it would encourage public reflection and conversation.

Moreover a key part of the campaign was its website. Blogs on the website written by eight different HIV-negative and HIV-positive men invited men visiting the site to respond to the issues raised and to post comments.

Over five months, the web site had 20,844 unique visitors (80% from Ontario), who stayed an average of six minutes per visit. Some 4384 visitors came back to the site ten times or more.

The researchers describe the blog discussions as “lengthy and lively”. Topics included the sources, forms and consequences of HIV stigma; how to separate rejection of the virus from rejection of men who have the virus; the ethics and practicalities of disclosure of status; challenging stigma; and responsibility and consent in HIV transmission.

Evaluation

Despite the central role of behaviour change media campaigns in many countries’ HIV-prevention programming, careful evaluation of their impact remains rare.

The evaluation described here is not a randomised control trial (which provides the most reliable form of evidence), but assessed the impact of the campaign by means of cross-sectional surveys before and after the intervention. The campaign was promoted throughout the province of Ontario (including Toronto, a major gay centre) and was largely delivered via the internet, so it would have been difficult to identify a control group of gay men who were not exposed to the campaign and who had similar characteristics to those in Ontario.

Recruitment to the before and after web-based surveys was by identical means (an e-mail to local subscribers of a cruising website, www.squirt.org), and this was separate from delivery of the media campaign. A total of 1942 and 1791 men took part in the first and second survey, respectively. The characteristics of those taking part were broadly similar on each occasion.

Of those completing the second survey, 42% were aware of the campaign. Awareness was higher in gay-identified men, residents of big cities, men under the age of 45, better-educated men and men who reported unprotected sex with casual partners. Awareness did not vary by ethnic group or income. But far more HIV-positive men (68%) than HIV-negative men (42%) or men of unknown HIV status (31%) recalled the campaign, perhaps suggesting that its themes were particularly salient for men with HIV.

In terms of attitudes towards disclosure, the men who completed the pre-campaign survey had similar responses to the men who completed the second survey but weren’t aware of the campaign.

Moreover, comparing respondents of the second survey who were aware of the campaign with those who were not, there are statistically significant differences in their attitudes, even after controlling for confounding factors such as age, HIV status and sexual risk behaviour. The researchers believe that this shows the impact of the campaign on those who saw it.

Men who were aware of the campaign were more likely to agree that “gay men with HIV face stigma and discrimination within the gay community” (odds ratio 1.82) and that “gay men with HIV are reluctant to disclose their HIV status to their sexual partners because they do not want to be rejected” (odds ratio 1.48).

They were less likely to use terms like ‘clean’ or ‘disease-free’ when cruising for sex on-line (odds ratio 0.64) or to seek sexual partners with the same HIV status as a way to prevent HIV transmission (odds ratio 0.67).

They were also less likely to agree with the following statement: “If a gay man has HIV, there is no excuse for him not to talk about his HIV status before having sex with a new partner” (odds ratio 0.63). Nonetheless a large majority of respondents did agree with this statement – 85% of those unaware of the campaign, and 73% of those aware of it.

The authors believe that these results, along with the extensive activity and postings on the campaign website, “indicate that the site struck a chord with many community members and stimulated dialogues that likely spilled over into other contexts of daily life… Those who were aware of the campaign were significantly more aware of stigma and its role in HIV transmission at the conclusion of the intervention.”

Adam BD et al. hivstigma.com, an innovative web-supported stigma reduction intervention for gay and bisexual men. Health Education Research 26: 795-807, 2011. Click here for the free abstract.