This week the OraQuick In-Home HIV Test, which will be sold over the counter and used without medical supervision, received its final approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), meaning that it can be legally sold in the United States. Similar approvals may follow for other countries. But who is likely to use it and in what circumstances? And will the increased accessibility of HIV testing make any difference to the epidemic?

Whereas French research suggests that men who are secretive about their homosexual behaviour will have a particular interest in home testing, a study from New York indicated that some gay men will use it to test sexual partners, sometimes as a prerequisite for unprotected sex. And a rich discussion between HIV prevention advocates and researchers, which recently took place on the email forum of International Rectal Microbicide Advocates (IRMA), highlighted the key issue of whether people who test positive at home will subsequently connect with health services. While some participants had concerns about the potential for coercion and abuse, others felt that home testing could increase choice and autonomy.

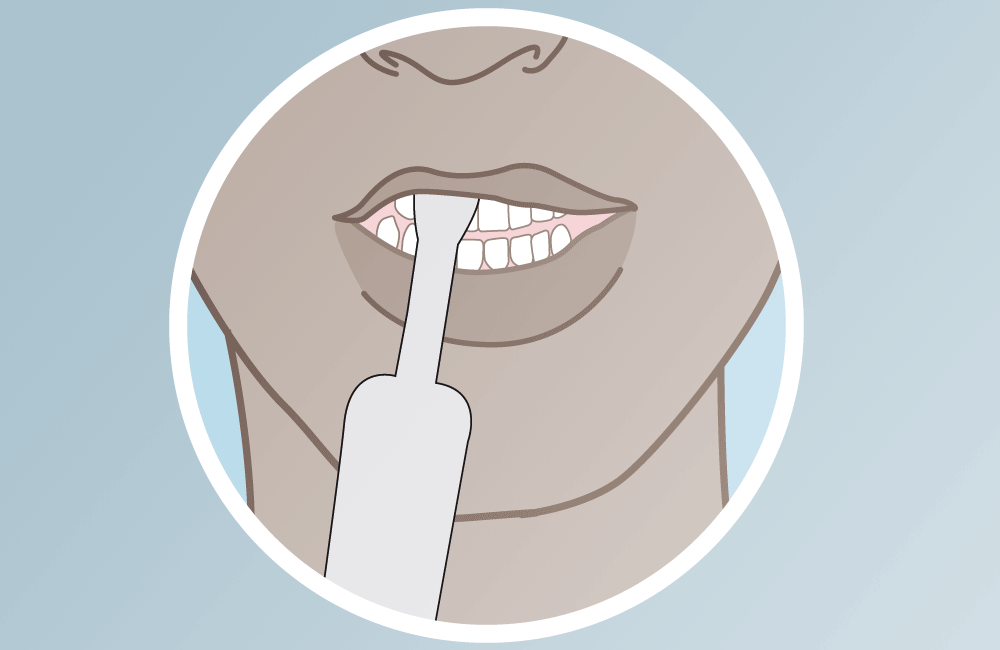

The OraQuick In-Home HIV Test will be sold from October onwards in pharmacies and over the internet, for a price somewhere between $20 and $60. The packaging will include instructions, advice on what to do after getting the result and details of a 24-hour phone helpline. The test's sample is taken by swabbing an absorbent pad around the outer gums, adjacent to the teeth; the results are given in twenty minutes.

At a hearing in May, the members of an FDA advisory committee voted unanimously that the benefits of the test outweigh its potential risks for consumers. While the test is not as accurate as professionally administered tests, the panel felt it could provide an important way to make HIV testing available to more people.

At the FDA hearing, there was overwhelmingly supportive public testimony from HIV activists, black community representatives and public health experts. Nonetheless, in the days that followed, some advocates raised a number of concerns.

For many advocates, a key issue is the support that can be offered by professionals during the testing process. “HIV testing is not a matter of poking the person, sitting quietly for 15 minutes and then sending them on their way without any other discussion,” as someone commented. While testing is going on, there is a dialogue about why the test is being done, what the test is for, what the results mean, safer sex practices and referrals to other services. Moreover, there is considerably more talking should the result turn out to be positive.

Many feel that this personal, direct discussion cannot be replicated with a pamphlet, which may or may not be read and understood.

This puts testing into the hands of the individual, not a healthcare professional.

Some people fear that the limitations of the test will not be fully understood. In the trial that led to the test's approval, 7% of people who really did have HIV received false-negative results. Moreover the test has a considerable window period – a negative test result is not considered accurate if a risk has been taken in the previous three months.

But others point out that the window period problem has always been with us. “Many people – perhaps most – assume that all is well after a visit to the local clinic and an antibody negative result,” noted Timothy Frasca of the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies in New York. He suggested that people’s behaviour is not necessarily influenced by the cautionary messages they hear from healthcare staff.

A number of advocates felt quite strongly that despite certain limitations of the home test, its key advantage is that it puts testing into the hands of the individual, rather than being controlled by healthcare professionals. “Attempts to overly mediate how I receive information about my body amount to little more than a paternalistic view of what I can handle,” said Jerome Galea of Epicentro in Peru.

Galea went on to say that while many people will continue to want and need in-person counselling and testing, those who do not should not be forced to have it. He said that he’d probably had about 50 tests in the past 25 years and doesn’t need to go through the counselling again.

Who will want to use a home test?

Studies are beginning to highlight particular uses of home testing and particular groups who are likely to use it. Much of the research to date has been with gay and bisexual men.

For example, French research suggests that gay and bisexual men living away from the big cities and those with concerns about privacy are the most likely to use home tests. Tim Greacen and colleagues recruited over 9000 men for an online survey and found that 30% had already heard of home tests, but 70% had not.

Among the HIV-negative men who hadn’t previously heard of home tests, 86% said they would be interested in using one.

The main reasons to be interested in the home test are its convenience, accessibility, rapidity and privacy.

Men who were interested tended to live their male-male sex life in total secrecy, live in a conventional family structure and live in smaller towns. There were also associations with being employed, being less educated, never having tested for HIV, testing for HIV infrequently, and having unprotected anal sex with casual partners.

Respondents said that the main reasons to be interested in the home test were its convenience and accessibility (31.5%), rapidity (28.5%) and privacy (23.2%).

Among men who had previously heard of tests, 3.5% (69 men) had used one. They had mostly been purchased illegally through the internet. Men who lived their male-male sex life in total secrecy were almost four times as likely as men who were open to have used a home test (odds ratio 3.9).

Three men got a reactive result from the home test – in other words, one which could indicate a positive result but which needed to be confirmed by further testing. Two men did seek further tests (one took another home test, the other went to a professional laboratory), but the third man did not, although he did call a telephone helpline. None of the three men had seen a doctor about their test results.

Linkage to care

The question of what happens to people who get a reactive (‘positive’) result is crucial to David Barr of the Fremont Center. “The failure of HIV testing is our poor linkage from testing to care,” he said. “This failure is present in pretty much every approach to testing, with many, many testing programmes not even considering linkage to care a priority – their responsibility ends with testing, counselling and perhaps, a referral.”

He is concerned that this will be a particular weakness of home testing. “Self-testing, by its nature, will only link people to care in passive ways,” he said.

“The failure of HIV testing is our poor linkage from testing to care." David Barr

Others point out that, in many places, post-test support is already inadequate, as demonstrated by the large number of people who hide themselves from health services after receiving a positive diagnosis. In which case, perhaps an alternative approach is warranted.

Ebony Johnson of the Athena Network spoke of services which are over-burdened and under-staffed, and where some workers lack training and cultural competency in relation to HIV and confidentiality. As a result, some people are fearful of testing in some clinical services. “At home testing may provide the autonomy and privacy that some need in order to digest their diagnosis,” she said.

Charles King of Housing Works noted how the arguments against home testing "closely tracked the arguments against over the counter pregnancy tests" in the 1970s. At the time, there was widespread concern that adolescents would misuse pregnancy tests (if they could afford them) or that those finding out they were pregnant without professional support would not take confirmatory tests, would not connect with clinical services, would self-harm and would suffer violence from their parents or boyfriend. These fears turned out to be largely unfounded.

Screening sexual partners

One of the particular scenarios that has been much discussed and cited as a potential misuse of home testing is of people asking sexual partners to take HIV tests, perhaps immediately before intercourse. Apart from the possibility of partners being pressurised to test against their will, the other fear this plays on is of individuals using negative results as a license to have unprotected sex, regardless of any information about the test’s limitations.

“It is interesting to me, and not a little sad, that so many of us conjure up hypothetical worst-case scenarios of sexed up gay men behaving recklessly,” commented Jim Pickett, chair of IRMA. He pointed out that testing is a health-seeking behaviour and something that advocates normally greatly encourage. “Why must our hypothetical scenarios always bend toward gay men behaving ‘badly?’” he asked.

In fact, the French study discussed above found that just 4.5% of men interested in home tests said they wanted to test their partners.

Men could see that taking a test could easily be a mood killer when meeting a sexual partner.

Rather different results have come from a study in New York, but this may be an artefact of different recruitment methods and the way in which the American interviewers actively raised the topic of testing before sex.

Alex Carballo-Diéguez, Timothy Frasca and colleagues recruited ‘high-risk’ HIV-negative gay or bisexual men who regularly had unprotected receptive anal intercourse and who were interested in talking about home testing. Fifty-seven men completed the surveys and in-depth interviews.

In total, 87% of participants said that they would use the test. Moreover, 80% would use it with sexual partners at home.

The interviews explored how men envisaged using the test, in particular with sexual partners. Men expressed a variety of opinions about when to bring the issue up, where and with who.

One man said:

“I guess before we leave the bar, like, so, Are you a top? Are you a bottom? Oh, you’re bottom, great, I’m a top. That’s good. HIV negative? Positive? . . . Negative? Cool. You’re not going to feel funny about me asking you to take the test, right? Because you know, I got—I went to [name of drugstore] last night and I bought a bunch of them so we’ve got to put the bitches to use. I test everybody…”

But men could see that taking a test could easily be a mood killer when meeting a sexual partner. In fact, the same man who was quoted above could also see how badly he might react if someone asked him to take a test before sex.

“I’d probably freak out… Like, what, who are you? Are you trained to do this? Like, who are you? Like, I’m just coming over to fuck you.”

If a casual partner’s result was reactive (‘positive’), most men didn’t anticipate continuing with sex. Some said they would show empathy and try to be helpful.

Men noted that the test itself couldn’t be used in many environments where men meet for sex (such as saunas or sex clubs) and that use would be tricky if men were high on alcohol or drugs.

Some men thought that raising the issue of testing would require the intimacy of being at home.

“I will slowly, slowly talk my way into it, or persuade the person to take an interest in it. I probably would do it first so that somebody could feel comfortable with it.”

Moreover, some men felt that the test could be used as a relationship moved from casual to being more steady. But if either partner’s test was reactive, this was thought to be extremely problematic. It could signify the breaking of an agreement either to be monogamous or to always use condoms with other partners. Reactions could be aggressive or violent.

Inequalities

There are particular concerns about people being coerced into testing in situations in which there are already stark imbalances of power. Women and children may be particularly likely to suffer.

The way in which the test is priced, distributed and promoted may be crucial in determining whether it is used by those who are most at risk.

Paul Semugoma recalled an incident when a woman was brought by her in-laws for testing at his medical practice in Kampala, Uganda. “They were sure she would infect their son, so the family had mandated that she tests, and had sent a sister in law to observe the test,” he said. “That's the kind of situation in which I would imagine a family meeting being called and the lady being forced to take the test, before everyone.”

Andrew Hunter of the Global Network of Sex Work Projects commented: “For the millions of sex workers and others already facing compulsory testing, this could well be another way for brothel owners, mafias and corrupt cops to be able to enforce even more testing.”

But some see home testing as offering particular possibilities to marginalised groups – such as men who have sex with men and injecting drug users – in places where they currently have poor access to health services.

And despite the limitations and possible abuse of home testing, Paul Semugoma felt that it could be of real benefit in resource-limited settings. “The testing that is given by NGOs and government is still falling far behind what is required,” he said. Long waiting times, poor confidentiality and staff stigma put many people off. “A commercially available test at a pharmacy or drug shop, if competitively priced (meaning it is low enough for uptake) would be the best,” he continued.

Cost could also be a barrier in richer countries. “We want to be sure this will be accessible to those most at risk, who tend to be poorer, and not in the health care system,” commented Jim Pickett. “We don’t want this to be just some niche product for the ‘worried well’ in the suburbs.”

The US regulators took the view that a home test would lead to more people testing more often, and so lead to a reduction in the number of undiagnosed infections. But the way in which the test is priced, distributed and promoted may be crucial in determining whether the test is used by those who are most at risk and so whether home testing makes a real difference to the epidemic.

Greacen T et al. Internet-using men who have sex with men would be interested in accessing authorised HIV self-tests available for purchase online. AIDS Care, online ahead of print, 2012. DOI:10.1080/09540121.2012.687823

Greacen T et al. Access to and use of unauthorised online HIV self-tests by internet-using French-speaking men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections, online ahead of print, 2012. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2011-050405

Carballo-Diéguez A et al. Will Gay and Bisexually Active Men at High Risk of Infection Use Over-the-Counter Rapid HIV Tests to Screen Sexual Partners? Journal of Sex Research 49: 379-389, 2012.