The 2018 report from Public Health England is entitled Progress towards ending the HIV epidemic in the United Kingdom, and for once the note of optimism in the title is justified.

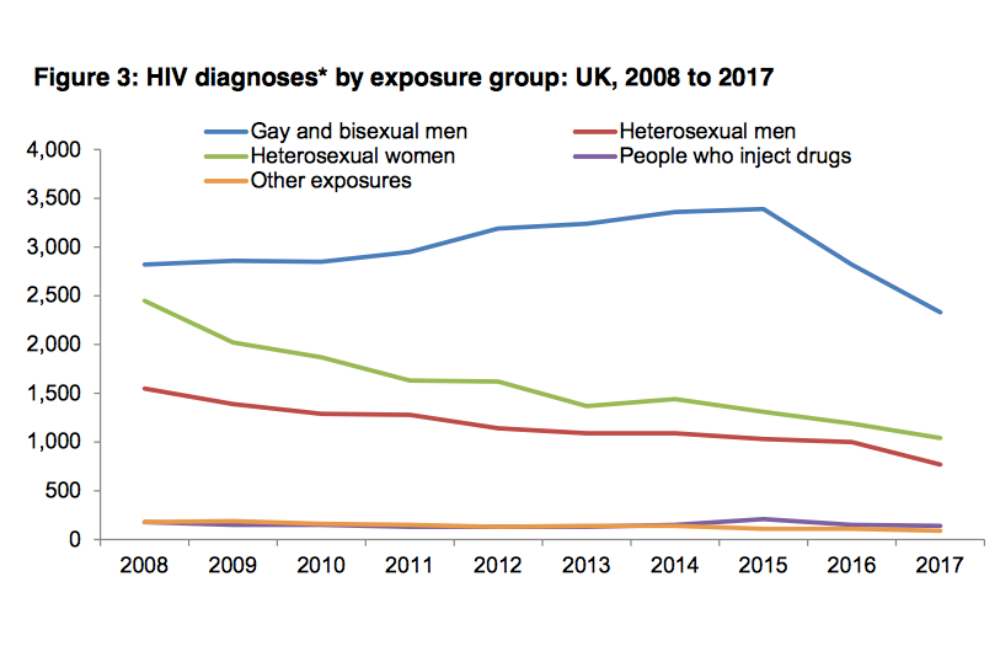

The report describes an epidemic in which new diagnoses fell in gay men, heterosexuals and all other groups; in people born in the UK and immigrants; in people of all ethnicities and age groups; and in virtually all regions of the UK.

It also shows that new infections – true incidence – have been falling even faster, so that within the last five years the proportion of new diagnoses that were of infections acquired in the last year has fallen from 80% to 50%.

Viral suppression, diagnoses and incidence

Public Health England (PHE) compares the UK’s performance to the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target, whose aim is that countries should have 72.9% of their people with HIV diagnosed, in care and virally suppressed by 2020. The UK has in fact already reached the subsequent UNAIDS 95-95-95 target of 85.7% of people virally suppressed – an estimated 87% of people with HIV in the country have an undetectable viral load. While ‘only’ 92% of people with HIV are diagnosed, 98% of those diagnosed are in care and 97% of those in care are virally suppressed.

During 2017, new diagnoses among all people fell by 17% on the previous year. In gay men they have fallen from 3390 in the peak year of 2015 to 2330 in 2017 – a 32% decline, as already reported on aidsmap.com. Diagnoses have fallen relative to 2016 in every area of the UK, with a particularly sharp fall in Wales. The exception is Northern Ireland, but numbers there are low and this region has also experienced a significant decline in diagnoses since 2011.

Diagnoses have fallen among every sexuality, gender and ethnicity group, not just in white gay men. There are two groups among whom a fall in diagnoses is new. One is white heterosexuals – diagnoses among men fell 31% and among women by 16%, relative to 2016. The other is black and minority-ethnic gay men, in whom diagnoses were previously not falling. Last year, they fell by 57% in black men, 22% in Asian men (where they had been significantly increasing), and 36% among other/mixed ethnicities. Diagnoses also fell among heterosexuals of African and Caribbean ethnicity who were born in the UK.

The numbers of people diagnosed late, with a CD4 count of below 350 cells/mm3, also fell. The decline was most marked among black African women and men (decreases of 82% and 79% since 2008, respectively). However, as reported previously, these absolute declines are largely because of a fall in all diagnoses and 52% of African heterosexual women and 69% of men are diagnosed late, compared with 52% of white heterosexuals and 33% of gay men. A quarter of those diagnosed late are diagnosed with CD4 counts below the AIDS-defining limit of 200 cells/mm3.

Probably more impressive even than the decline in diagnoses is the decline in the actual number of new infections – incidence. This is estimated with data from the 47% of new diagnosed people who have a recency (RITA) test, which can detect infections acquired in the last six months, as well as CD4 back-calculation, which computes date of infection from average CD4 count decline.

PHE estimates that last year there were most likely about 1200 new infections in gay and bisexual men (with a range of uncertainty between 600 and 2100), which is a reduction of 56% from the estimated peak of 2700 in 2012. Only 286 men tested with RITA showed evidence of infection in the last six months.

The proportion testing positive who had recent infection rose to a peak of 36% in 2014 but has since declined. This is revealed indirectly by the ratio of new infections to new diagnoses. In 2012-2015 the majority of diagnoses in gay men were of recent infections, with a ratio of 0.8 new infections per diagnosis, but it is now down to 0.5.

In other words, increased testing initially uncovered a lot of recent infections but with the further increase in testing and viral suppression, the proportion of infections diagnosed that are recent has now fallen. More infections diagnosed are now of chronic infections that people have been living with for several years.

PHE do not provide incidence estimates for other groups as fewer are tested with RITA and the uncertainty is greater.

How we could do even better – testing

We could do even better, including in relation to testing.

The BASHH/BHIVA testing guidelines say that gay and bisexual men should test annually for HIV, or every three months if they are having unprotected sex with new or casual partners. In fact last year only 42% of gay and bisexual men who tested for HIV at GUM clinics had tested at least once at that clinic in the previous 12 months.

The guidelines say that GUM clinics should aim to test 80% of all eligible attendees for HIV, but only 12% of clinics met this target. HIV testing coverage at GUM clinics is 89% in gay and bisexual men but only 59% in heterosexual women and 78% in heterosexual men.

The report reveals that increasing testing rates in places other than GUM clinics could further raise the diagnosis rate, especially in people who were not in the high risk populations of gay and bisexual men, people born in a high prevalence country, of black African ethnicity, or partners of people with HIV.

Because HIV incidence is falling in gay and bisexual men, the proportion of tests they take that are positive fell from 1.2% in 2016 to 0.9% in 2017. The positivity rate is now higher in some other groups – partners of people with HIV (4.3% of whom test positive when tested) and gay men with a recent anogenital bacterial STI (4.4%). The report recommends better contact tracing and that an STI diagnosis (in any part of the body) should be treated as a strong indicator for HIV testing.

Secondly, the yield is now greater in some other settings than in gay men going to GUM clinics. For instance, all prisoners should be offered testing for blood-borne viruses on an opt-out basis; 41,455 tests were carried out last year with a positivity rate of 1.1%. The yield in the national self-sampling service – where people test at home and post off samples for the result – is 1%.

Significant proportions of some groups are now diagnosed outside of GUM clinics, including women (38%), people of black African ethnicity (38%), people who inject drugs (52%), people over the age of 50 (42%) and people diagnosed late with HIV (41%).

How we could do even better – trans people, PrEP and condoms

Gender identity has only been recorded since 2015 on surveillance forms and during that time only 83 new diagnoses have been recorded among trans people, including eight in 2017. However clinics may still not be asking the right questions to identify trans people – a greater number of people (160) testing positive had their gender recorded as “other” and for considerably more it was not recorded at all.

One more way to further reduce HIV infections will be pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). PHE only has PrEP figures it is reasonably certain of from 2016, when is estimates that 3000 gay and bisexual men were taking PrEP. Since then the PrEP IMPACT trial has started with currently around 9000 people enrolled and there are probably a minimum of another 6000 people buying PrEP online. PHE comments: “It is very probable that the scale-up of PrEP use in 2016 and 2017 will have had a substantial effect at reducing underlying incidence, additional to the effect of intensified HIV testing combined with immediate treatment.”

Condom use, however, continues to slowly decline. In 2016, 60% of gay men reporting to the London Gay Men’s Sexual Heath Survey reported condomless anal sex in the previous three months, compared with 43% in 2000. Half of young people under 24 (of all sexualities) in another survey said they had had condomless sex with their most recent partner. PHE launched a campaign in 2017, Protect against STIs, aiming to reduce the rates of STIs among 16 to 24 year olds with condom usage.

Life expectancy and quality of life

In 2017 428 people with HIV died of any cause, the majority of whom (62%) were over the age of 50. The mortality rate – the proportion of people each year who died – was 0.308% (one in 325 people) in gay men, and 0.315% (one in 317) in heterosexuals. In injecting drug users, it was perhaps unsurprisingly higher at 1.421% or one in 70 per year.

However, the mortality rate in people aged 15 to 59 who were diagnosed with a CD4 count over 350 cells/mm3 was 0.12% (one in 820). This was actually lower than in HIV-negative people of the same age group, whose mortality rate was 0.166% (one in 602).

Mortality in the first year after diagnosis was the same as general HIV mortality, at 0.3%. but it was six times that figure – 1.8% - among adults diagnosed late, worse than that in late-diagnosed people over 50 where one in 26 people (3.85%) died within a year of their diagnosis. In 2017, 230 people were diagnosed with AIDS either at diagnosis or within three months of it, compared with 620 in 2008.

People’s health-related quality of life still lags behind that of the general population. The PHE report includes figures from the Positive Voices survey which was offered to randomly selected people in care and completed by 4424 people. In this, 73% of people with HIV rated their health as “generally good” compared with 81% of members of the general population.

The difference was largely driven by poorer mental health in people with HIV, where 50% reported symptoms of depression and anxiety, compared with 24% of the general population. Overall health was poorer in people who inject drugs (31% rated it as generally good) and trans/non-binary people (50%).

In other words, while we may be taking steps towards ending the epidemic of HIV, the epidemic of stigma and poor mental health that accompanied it is alive and well.

Public Health England. Progress towards ending the HIV epidemic in the United Kingdom: 2018 report. See assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/759408/HIV_annual_report_2018.pdf for a PDF copy of the report.

All graph images from the Public Health England report.