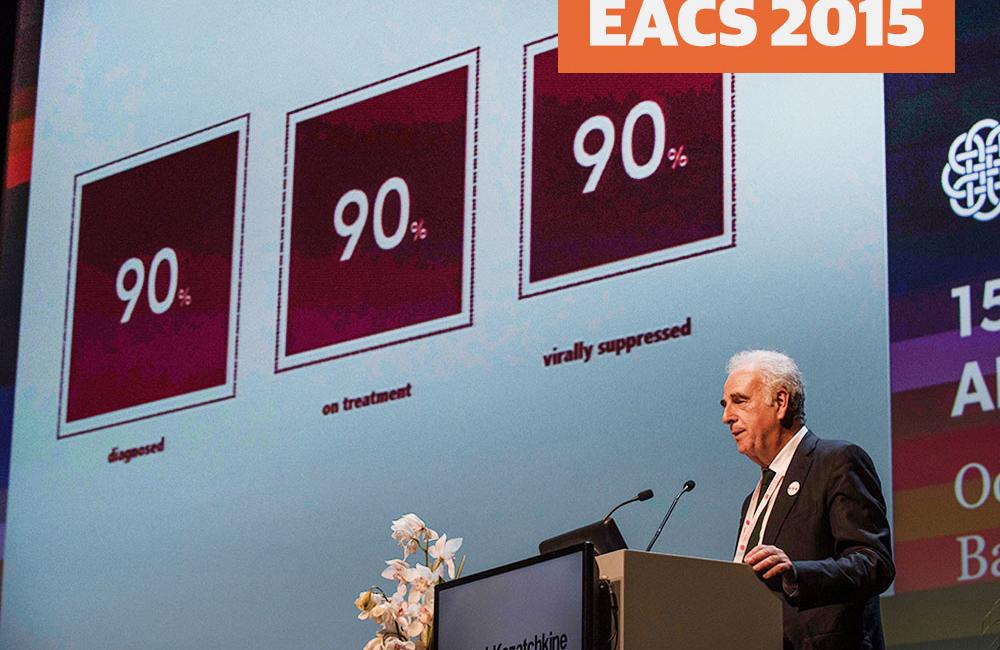

The European region needs to step up prevention and treatment activities if it is to reach the UNAIDS target of 90% diagnosed, 90% of those diagnosed on treatment and 90% of those on treatment with fully suppressed viral load by 2020, the United Nations Secretary-General's Special Envoy on HIV and AIDS in Eastern Europe and Central Asia told the opening session of the 15th European AIDS Conference in Barcelona on Wednesday.

The 90-90-90 target promoted by UNAIDS, if achieved, would result in 73% of people living with HIV having undetectable viral load. Mathematical modelling suggests that achieving this target by 2020 would end the AIDS epidemic by 2030.

“Europe is not done with AIDS and there is no room for complacency”, Professor Kazatchkine told delegates.

“There isn’t one Europe”, Professor Kazatchkine told a press conference on the opening day of the conference. The World Health Organization (WHO) Europe region covers 53 countries, and “in fact, there are three Europes – Eastern Europe, Central Europe and Western Europe – with different epidemics, different responses and different levels of success.”

The Eastern European epidemic continues to grow, driven largely by unchecked epidemics in people who inject drugs, but autonomous epidemics are also emerging in heterosexual men and women through sexual transmission in the region, Professor Kazatchkine warned. The high levels of transmission make it unlikely that Eastern Europe will be in a position to reach the 90-90-90 target by 2020, he said. Prevention services are not accessible at sufficient scale and access to harm reduction remains very limited. Very low levels of co-operation on the part of government towards non-governmental organisations impedes the scale up of prevention activities.

In Central Europe, despite low prevalence, HIV incidence has been rising gradually in many countries. The epidemic remains highly concentrated among men who have sex with men and people who inject drugs, but there is “limited willingness to pay” for programmes aimed at these vulnerable groups among governments in the region, Professor Kazatchkine said. He reminded delegates of the consequences of reducing HIV prevention services in the region: after Global Fund funding for harm reduction was gradually withdrawn from Romania when it joined the European Union in 2007, the country suddenly went from a minimal epidemic to high incidence among people who inject drugs in less than two years.

Although Western Europe appears to have everything needed to mount a successful response to HIV, the overall level of new infections has remained stable over the past decade. Despite universal health coverage, excellent HIV care and high levels of social support, new infections have increased among men who have sex with men over the past 10-15 years. Much more intense efforts are needed in both prevention and treatment, but the 90-90-90 targets should be achievable for both Western and Central Europe, he predicted.

But, he told the conference, “If we do not intensify our efforts in the next five years we will not be on the path to ending AIDS.”

“We need to look carefully at the weaknesses in the European response. We are still missing many infections among men who have sex with men and migrants from countries with generalised epidemics,” said Professor Kazatchkine. In particular he expressed concern about testing frequency among men who have sex with men: if a large proportion of new infections among men who have sex with men are a consequence of acquiring HIV from partners who are themselves recently infected, yearly testing may be too infrequent to pick up recent infection and start treatment early enough to interrupt a chain of new infections. “Self-testing will be one of the solutions,” Professor Kazatchkine suggested.

A focus on the groups of people left behind will also be necessary: people who inject drugs, migrants, sex workers and men who have sex with men continue to lack access to testing, treatment and care in many settings in the region, yet are the groups most affected by HIV.

Closing the treatment gap will also be necessary in order to reach the 90-90-90 target, he said. At the moment the number of new HIV diagnoses in many countries in Eastern Europe continues to exceed the number of people who start treatment each year, which means that the treatment gap is growing, not shrinking. The treatment gap is made worse by national guidelines restricting treatment to people with CD4 cell counts below 350 throughout Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and by alarmingly poor rates of diagnosis and retention in care. The average treatment cascade for the region as a whole shows that only 47% of people living with HIV know that they have HIV. In the Russian Federation, the country with the largest number of people living with HIV, only 12% of people living with HIV are on treatment.

Late diagnosis continues to be a major challenge for achieving high treatment coverage in Western Europe, especially among migrants who often lack good access to health care. In Eastern Europe, treatment coverage is around 35%, compared to a global average approaching 60%, Professor Kazatchkine told a press conference. “People are very reluctant to go to services because of stigma and discrimination, because of a lack of co-ordination between TB and HIV services, and because of criminalisation of people who inject drugs." Less than 10% of people who inject drugs who are living with HIV are currently accessing treatment in Eastern Europe, Professor Kazatchkine said.

Tamas Berezcky of the European AIDS Treatment Group said that stigma and discrimination are the biggest barriers to testing and treatment among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Central Europe, and stigma within the community is an important barrier to seeking care. “If you look at how men who have sex with men treat other MSM with HIV it’s very depressing,” he told the press conference. He said that stigma is being reinforced by a lack of information about HIV, including a lack of awareness regarding recent advances in HIV treatment, the normal life expectancy of people who receive appropriate antiretroviral treatment and the impact of treatment on transmission.

There is also insufficient focus on partnership with community organisations, Professor Kazatchkine said. Tamás Berezcky called on scientists to join in partnership with the community to achieve implementation.

The financial sustainability of the HIV response in Eastern and Central Europe is also a serious concern following the withdrawal of Global Fund support for HIV and TB programmes in the region. Global Fund support has come to an end as a result of a decision to focus future funding on lower-income countries, despite the political difficulties of funding the necessary prevention and treatment services in Eastern Europe.